Jamie Breedlove didn't want to die as the wrong person. Breedlove, 65, had spent most of her life doing what was expected of "macho men." She learned martial arts, took up whitewater rafting and rock climbing, married four times and served in the Navy. All that time she struggled to deny a powerful and life-altering feeling: "I must be female."

As she aged, she remembers reading and hearing about people who were assigned one gender at birth but openly identified as being another. Breedlove saw how people like this were becoming more accepted and protected.

"As I got older, I said, 'Aw heck, I'm too old to transition,'" recalls Breedlove. She wrestled with the idea, asking herself, "Is this the right thing to do? Is this what I really want?" But given her age, she concluded, "I don't want to die in the wrong body."

Now death is very real for Breedlove, who lives in Spokane. This year she was diagnosed with an aggressive type of throat cancer. The medication her doctor gave her didn't work. The cancer threatens her life. But she's at peace.

In fact, she's happier than she's ever been. In 2013, Breedlove transitioned from a male to female. She started making trips to thrift stores to donate her old jeans and button-down shirts and to buy dresses, blouses and cardigans. She grew her hair long and dyed it auburn. She wears a stud in her newly pierced nose. She wears makeup and sports bright-pink fingernails. She takes estrogen and testosterone blockers.

"My peace is I'm going to die as Jamie, not Jim," says Breedlove.

Transgender people like Breedlove — those who don't identify with the gender they were assigned at birth — have long been the butts of jokes, easy targets for harassment or violence and relegated to the fringes of society where they've battled high rates of poverty and suicide.

In recent years, they've rapidly moved to center stage, appearing on the covers of magazines, in television and film and even serving openly in the Obama administration.

"We have gone through iterations of this," says Danni Askini, executive director of the Seattle-based Gender Justice League. "It's trans people now; it was gays and lesbians in the 1990s and 2000s."

Over the past two decades, gays and lesbians have steadily gained more rights, and the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately legalized same-sex marriage last year. But, Askini adds, "There is a low level of understanding with the public of transgender people and who they are."

The number of Americans who identify as transgender is nearly 700,000, according to a study by the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law, making them less than 1 percent of the general population. According to a 2015 Harris Poll, just 16 percent of Americans know someone who is transgender. This relatively small group faces an outsized amount of discrimination. Research shows that this population is four times more likely to have a household income of under $10,000 than the general population. Forty-one percent attempt suicide.

Governmental organizations ranging from the city of Spokane to the U.S. Department of Justice have enacted protections for transgender rights, while the science has largely been settled, with major medical and psychiatric associations adopting more accepting standards of care for these individuals.

But new protections, meant to safeguard the rights of transgender people from the bathroom to the workplace, have opened up a new front in the culture war that extends into Idaho and Washington.

Over the past decade, the two states have taken divergent paths regarding protections for this population. Washington has embraced civil rights laws for transgender people, while Idaho has largely resisted them.

Now the trajectory of both states could change. Washington is preparing for a potentially divisive ballot initiative that would roll back a protection for transgender people, while in Idaho this population is becoming more visible as advocates renew their efforts for increased recognition of their civil rights.

Askini says there's an opportunity for more understanding of transgender people as they become more visible. But she says that as society figures out which bathrooms they're allowed to use, what medical care they're entitled to and what other rights and protections to assign this group of people, there's a potential for a backlash.

"There is a lot of fear in our community," says Askini. "It is a scary time for us."

Through The Ages

They've been here all along. Although the term "transgender" didn't exist, there are accounts throughout the 1800s of men and women whose gender identity didn't match that of their assigned sex. Women assumed male identities to fight in the Civil War and kept their personas after the conflict ended. As the U.S. industrialized, urban centers formed, which some historians have argued allowed people who didn't conform to society's expectations of their assigned gender to congregate, form communities and become more visible.

In the 1950s, Americans were introduced to Christine Jorgensen, a former Army private who traveled to Denmark for hormone treatment and gender-reassignment surgery and became a media spectacle upon her return. "Ex-GI Becomes Blonde Beauty" read a 1952 headline in the New York Daily News.

In 1989 the death of Billy Tipton, a well-regarded jazz musician who settled in Spokane, revealed that the Oklahoma-born pianist and saxophonist was born a woman but presented himself as a man in order to be accepted in the male-dominated music industry. The revelation came as shock to his three adopted children and the five women he married over the course of his life. Tipton's life inspired operas, novels, plays and songs. But over the course of Tipton's lifetime, much of the public lacked a frame of reference to understand people like him.

"We know when we're very young that there's something different," says Breedlove of transgender people. "We don't have a word for it or a description for it when you're that young."

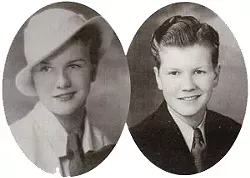

Growing up in conservative Richland, Washington, in the 1950s and '60s, Breedlove had a vague awareness of transgender people she gleaned from books. To her, it was something done by "people in a far away place." The idea was uncomfortable, not something that "regular people" did. But she kept gravitating towards feminine things. Sometimes she would secretly try on her sisters' shoes or clothes. "I wish they were my clothes," Breedlove recalls thinking. "They get to wear these all the time."

As Breedlove grew older, she kept this part of herself hidden away. In keeping with her macho persona, she joined the Navy in 1968. While on shore leave in places like Japan, Australia and Thailand, Breedlove would slip away and try to be a "regular girl." She would wear long, flowing dresses, women's underwear and long, dark wigs that hid her clipped hair. Sometimes she would find a gay bar. Other times she would just find a park and read. When she returned to ship, she would hide the wig and clothes in her locker and live in a state of fear that they would be discovered during an inspection. After being discharged from the Navy in 1975, Breedlove attended graduate school, taught at colleges and universities and tried to live a normal life.

Meanwhile, the rights of gays and lesbians became mainstream. States and local governments started passing anti-discrimination laws aimed at protecting the rights of gays and lesbians. Spokane passed its own ordinance in 1999 protecting gays and lesbians.

But legal protections for transgender people have lagged behind. Beginning in 1993, Minnesota lawmakers passed legal protections for transgender people. Since then, more than 200 American cities and counties, as well as 17 states, have enacted similar protections.

Major medical associations also have called for health care providers to change how they treat transgender people.

"They are recognizing that [transgender] people are not just making this up and saying it to get privileges," says Jamison Green, president of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. "Transgender people are not crazy; they are not villains."

In 1980, the American Psychiatric Association added gender identity disorder to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the bible of mental conditions for mental health providers. The classification helped transgender people get some treatment, but it still labeled them as having a "disorder," which carried a stigma that made it easier to describe the community as mentally ill or delusional. In 2012, the APA, after a review of literature, issued a landmark revision to the manual changing "gender identity disorder" to "gender dysphoria," a condition marked by emotional distress from "a marked incongruence between one's experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender."

The update was accompanied by a statement noting the discrimination and violence that transgender people commonly experience. The reclassification meant that transgender people are no longer medically labeled as having a mental "disorder" that can be used against them and can more easily access treatments that affirm their identity. Similarly, in 2008 the American Medical Association passed a resolution labeling gender dysphoria a "serious medical condition" and called for insurance companies to cover mental health care, hormone therapy and sex reassignment surgery.

"Basically [those updates] mean that trans people are being recognized as human beings deserving appropriate health care and it's no longer appropriate to say you don't matter because you're trans, which is what people have experienced historically," says Green.

He says the science is still emerging on what causes gender dysphoria, but the origins are likely biological. He says that once transgender people start hormone therapy, they report feeling relaxed and "normal."

"Where does that come from?" asks Green. "That's got to be coming from somewhere."

After decades of internal struggle, Breedlove feels closer to normal than ever. Her transition has given her new perspective. She doesn't know how she got by without a purse before. She now regrets complaining in the past to wives and girlfriends about taking so long to get ready and not noticing all the times they got their hair styled. She legally changed her middle name to "Eleanor," after her 92-year-old mother who she says doesn't understand her transition.

Although gender reassignment surgery is covered by Medicare, Breedlove says she's having a hard time finding a doctor in Spokane who will take its low reimbursement rates. She says she may have to start working again to pay for it. "This is my goal," she says. "I want to get there as soon as I can."

Last year, Breedlove began celebrating July 11 as her "second birthday." It's the day she got her driver's license designating her as female. She recalls wanting to run down the streets yelling, announcing herself to the world. She ecstatically called her friends, and that night, they all went to the Park Inn bar on Spokane's South Hill to celebrate.

'This is Idaho'

A church may seem like an unlikely place for a meeting like this.

On the first Tuesday of every month, dozens of adolescents gather in the parish hall of St. Luke's Episcopal Church in Coeur d'Alene. Some drove with their parents from Sandpoint or Moscow. Some didn't even tell their parents they're here.

This is the monthly meeting of the local chapter of Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG), and Jenny Seibert, a transgender woman who introduced Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders at his Spokane appearance in March, is telling the youths to be cautious about being out in an environment like North Idaho.

"It is absurd; it really is," Seibert tells the crowd. But she, adds, "this is Idaho."

While Seibert speaks, Juli Stratton stands in the back of the room and listens. Stratton founded this group after moving to Coeur d'Alene from Chicago seven years so her partner, now her legal wife, could take a job and be closer to family. In the beginning, she expected no more than a handful of gay, lesbian or gender-nonconforming adolescents to show up to meetings. But this group has only grown, and she hopes it'll change attitudes.

"[Coming here] was the Twilight Zone for me," says Stratton. "I felt like a big gay fish out of water."

In Chicago, Stratton had lived in Boystown and Andersonville, two of the city's gay-friendly neighborhoods. But in North Idaho, she saw no rainbow stickers anywhere and no mentions of gays or lesbians in the newspaper. She fell into a depression until she decided to start attending meetings of the Spokane chapter of PFLAG, a national organization that provides advocacy and education on behalf of LGBT people. The first meeting she attended was in a church that had a rainbow flag and a "no hate banner" displayed inside. Stratton says she immediately burst into tears.

While attending meetings, she met people who also traveled from Coeur d'Alene to attend, and they figured they could start meeting at home. In April of 2013, PFLAG Coeur d'Alene held its first meeting in a cramped room in the downtown library, drawing an unexpected number of 25 people who heard about the meeting through word of mouth and on Facebook.

Each month, PFLAG brings in guest speakers to talk about their experiences or watch educational videos. It holds social events and support groups, including one for gender-nonconforming youths. Now, sometimes up to 60 people attend meetings, says Stratton, in a "sacred, safe space."

"When you look at the climate in Idaho, it's one of fear of coming out," says Maureen Finigan, who took over as president of PFLAG Coeur d'Alene earlier this year and notes that many members worry about being attacked or even killed.

In the 1990s, Bev Moss formed a chapter of PFLAG in Coeur d'Alene after her 16-year-old daughter came out as gay. At the time gay marriage was nearly unthinkable, and the Aryan Nation was very present in North Idaho. The group met in a church basement, but it fizzled as their kids grew up.

"We were pretty closeted as a group," recalls Moss.

But Stratton says the new incarnation of PFLAG wants to be part of the community. And, she says, it has a simple message: "We're really not different with what we want to do with our lives. We want fair wages for a job, we want the opportunity for jobs, we want the opportunity of marriage."

Last year, PFLAG had an entry in the Coeur d'Alene's St. Patrick's Day parade. It was the group's first public foray and Stratton was nervous. Thirty people, including business owners and members of the group, marched down Sherman Avenue with a banner reading "Pride In Community — Honoring Diversity." No one heckled or threw things, says Stratton. They later marched with the Kootenai County Democrats in the Fourth of July parade and will have their own entry this year. They also placed an ad in the paper for their annual rummage sale, a small measure of publicity they would have shunned in the past.

Finigan says they've had no backlash. No protestors outside of meetings, no angry confrontations.

"No drama," she says. "That is an amazing thing."

Earlier this spring, Stratton nervously dropped off an application to join the Coeur d'Alene Chamber of Commerce.

"They said, 'We're so glad you're here,'" says Stratton, adding that while the history of the area is associated with bigotry, "people are so tired of that reputation."

Steve Wilson, president and CEO of the chamber, says that white supremacist groups left a "big black mark" on the city that people want to scrub away. He points to an ordinance passed in 2013 that made it illegal for businesses, with a few exceptions, to discriminate against people based on their sexual orientation or gender expression.

"Generally speaking, what is socially correct is good economics," says Wilson of why his organization supported the ordinance.

Outside of the 12 Idaho cities that have ordinances banning discrimination based on people's sexual orientation or gender identity, it's legal to deny LGBT people housing or jobs. It happens. In 2013, a transgender woman was charged with trespassing in Lewiston after she tried to use the women's restroom at a Rosauers. According to a report from the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law, 78 percent of transgender respondents to a survey conducted in Idaho reported harassment or discrimination at work, and nearly half had been discriminated against in hiring, promotion or job retention because of their gender identity.

Since 2007, activists have been trying to convince lawmakers to add four words — "sexual orientation" and "gender identity" — to the Idaho Human Rights Act, a law that prohibits discrimination in educational, housing and workplace settings. But Idaho lawmakers have balked.

Chelsea Gaona Lincoln, chair of the Add the Words campaign, says that her group has new regional leadership and will be highlighting where legislative candidates stand on the issue.

Meanwhile, Stratton, who identifies as gender-non-conforming, says that while she's experienced no outright hostility in Coeur d'Alene, she gets strange looks and has had comments directed at her like "queer," or "is that a guy or a girl?" She says that most people just need to meet people like her.

"They need to know that we're not the scary things they have in their minds," she says.

Bathrooms and Ballots

In 2006, Washington lawmakers updated the state's Law Against Discrimination, effectively outlawing discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity for employment, insurance, housing and other areas.

Currently, an effort is underway to qualify a statewide ballot initiative that, if passed, would change how that law applies to which bathrooms and locker rooms transgender people can use. Late last year, the Washington State Human Rights Commission, an agency that interprets and enforces the state's anti-discrimination laws, issued a rule that requires any facility open to the public to allow people to use restrooms and locker rooms (including in schools) that align with their gender identity.

After the rule became public, calls to repeal it were swift, and Washington entered the culture war over transgender people and bathrooms.

"Parents have a right to expect that when their children go to school, the boys will use the boys' locker room and the girls will use the girls' locker room," reads a statement issued in January by state Sen. Doug Ericksen, R-Ferndale. "For political reasons the commission overturned a sensible and deeply ingrained cultural tradition without informing the public, telling the Legislature or even issuing a press release."

Earlier this year, states began considering so-called "bathroom bills," all of which concerned which restrooms transgender people could enter. During the most recent legislative session, Washington legislators considered a bathroom bill that would have undone the HRC's rule and would have barred the commission from issuing any regulations on gender-segregated facilities. The bill passed the state Senate but died in the House. Now a group of activists have begun gathering signatures and funds for I-1515, a ballot initiative that would undo the HRC rule and bar local governments from adopting laws that guarantee transgender people can use bathrooms of their choice.

The most notable bathroom bill is the one signed into law in March by North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory that would require people to use public bathrooms consistent with the gender on their birth certificates, while banning municipalities from enacting anti-discrimination ordinances. In response, the U.S. Justice Department has threatened legal action and companies have indicated they'll avoid the state, with PayPal notably announcing that they'd cancel an expansion in the state that would have created 400 jobs.

In May, the Obama administration issued a directive instructing public schools across the country to allow transgender students to use bathrooms and locker rooms that match their identity. Idaho joined 10 other states that responded with a lawsuit against the Obama administration over the directive, and Gov. Butch Otter has called it an "offensive attempt at social engineering [that] only harms our children."

"The rhetoric they are spewing is so hateful and so dangerous to transgender folks," says Jan Shannon, a assistant pastor at Spokane's Westminster Congregational United Church of Christ who is leading statewide efforts to oppose I-1515. "This is just unfounded fear, so we need to stand up to that, even if doesn't make it to the ballot."

But Kaeley Triller Haver, communications director for Just Want Privacy, the campaign for I-1515, says, "There are genuinely kind people who have legitimate concerns about this that don't have a voice in this."

Triller Haver says I-1515 has been unfairly conflated with North Carolina's law and points out that repealing the HRC rule wouldn't necessarily force transgender people to use bathrooms that match their birth certificate. Instead, she says, it would allow businesses to make their own decisions. Inside public schools, however, transgender students would have to use bathrooms of the gender they were assigned at birth. Under the initiative, students could sue a school for $2,500 if they encountered "a person of the opposite sex" in a bathroom or locker room.

Faith communities as well as victims of sexual violence — who may find it traumatic to encounter someone who is anatomically male in a women's locker room — have been left out of the conversation, she says. Triller Haver points to an incident in Seattle where a man entered a woman's locker room at a pool, citing his right to be there under the new HRC rule. She expects that rule will lead to similarly confusing and volatile situations.

"The rules don't say a man can go into a women's restroom, they say that a transgender woman can go in the women's restroom," responds Sharon Ortiz, executive director of the Human Rights Commission, who says there already are laws barring men from going into the women's bathroom.

Ortiz says that the rule just codifies how the commission has been enforcing the law since 2006. The commission began a public rulemaking process in 2012, but she says the HRC had budget cuts and major IT issues, making outreach harder.

Triller Haver says, "If they wanted people to know this, they could have told them; it's not hard."

She points to incidents where men have posed as women to enter women's restrooms to commit devious acts. But opponents of repealing the rule point to research showing that transgender people are already at a higher risk of being attacked or harassed than the general public, and that laws like this haven't led to an increase in assaults or voyeurism in restrooms.

Ortiz says that someone who has transitioned from female to male may look completely like a biological man. But if the rule were to be repealed, says Ortiz, that person could be placed in the potentially awkward or dangerous position of having to use the women's restroom.

"It's a very easy, scary trope that can be used to demonize people," says Green, of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, of concerns that allowing transgender people to use the bathroom of their choice will aid predators. "It's been done with every civil rights movement in this country. Every group that has been singled out has been told they can't use the bathroom."

Homeless & Transgender

For Rosie-Mae Green, a 24-year-old transgender homeless woman, using the bathroom is often a reminder that she doesn't look like a woman. Sometimes she can't shave and a thick beard sprouts up. Hormone treatment and surgery remain out of reach, she says. Although she knows that she can legally use the women's restroom, she often doesn't.

"I get told to use the men's room, or there are too many women in the women's room and they start yelling at me and causing fights with me," says Green, who lives in Spokane. "So I just use the men's room to avoid all that."

Sometimes she buys over-the-counter estrogen supplements, but she says people won't recognize her transition until she's on hormones.

Last year, Washington state began requiring Medicaid to cover hormone therapy and gender reassignment surgery for transgender people. Green is on Medicaid, but before getting these treatments, a patient has to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria by a qualified mental health professional. Green says that in Spokane she's had a hard time finding a counselor to work with her.

"Sadly, there aren't that many practitioners in Spokane," says Marybeth Markham, a counselor who specializes in helping transgender people, many of whom have been abandoned by family and friends. She says that the handful of doctors and mental health workers in Spokane who have experience working with this population isn't enough to meet demand. She also says she wants to accept Medicaid, but has yet to get through its red tape.

Green, of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, says that getting this treatment can be a challenge for people on Medicaid or Medicare because the reimbursements typically don't cover the physician's costs.

Rosie-Mae Green has been homeless since last October after her landlord told her to leave, which she suspects was because neighbors complained about her wearing women's clothing and "low-cut Gene Simmons boots." She sleeps on people's couches, in backyards and "anywhere I can lay my head down." But she avoids shelters operated by Union Gospel Mission or Catholic Charities, two religious social service nonprofits. She says she's been harassed while trying to sleep at Catholic Charities' House of Charity by other clients who screamed at her to get out. UGM won't let her in to eat lunch, she says, and told her "to come here as a guy or not come here at all."

When asked about its policies regarding transgender individuals, Catholic Charities responded with a statement from Rob McCann, its executive director, stating, "We follow all local, state and federal laws and guidelines related to issues of equal service delivery to all persons. We serve everyone at Catholic Charities regardless of religious beliefs, age, gender, race, disability, ethnicity, cultural background, or socio-economic status."

A statement provided by UGM notes that its"shelters are not equipped to serve all segments of the homeless population."

"Homeless families, individuals with serious mental illnesses, transgender, people with significant medical concerns or individuals who are unable to function independently are referred to other agencies better equipped to accommodate their needs," reads the statement.

Green says she's been jumped while dressed in women's clothes and she was confronted by a group of men who took her money. One of them drew a gun and told her they would kill her on the spot if they see her again.

She's applied for jobs in retail and fast food, but problems inevitably arise when she checks "female" on the application. When asked why she doesn't just check "male" on the application, she says she doesn't have the money for the fees to get her ID changed. Besides, she says, that's not who she is.

"I don't feel male," she says. "I'm female. I've always felt female. ... It's not a choice. You don't choose to be straight. I don't choose to feel like I'm female; I just am."

There have been 18 complaints made to the Washington State Human Rights Commission over the past three years alleging discrimination based on gender identity, two of which were from Spokane.

However, Ortiz says that there's likely more discrimination that the HRC does not hear about because people are afraid or think nothing will be done. The most recent National Transgender Discrimination Survey found that 72 percent of transgender respondents in Washington reported harassment or mistreatment on the job. Forty-two percent were not hired at all as a result of being transgender. Ten percent of respondents reported being evicted and 19 percent had become homeless because of their gender identity.

Green says that there are more people like her than most people realize. And, she says, "they all bleed red."

Always In Transition

The process of transitioning is never really complete, says Jamie Breedlove.

"No doubt I'm envious of the younger people," says Breedlove, who wonders what life might have been like had she transitioned earlier.

"Almost as ridiculous as it sounds sometimes, [I wish] I would have grown up and met a nice boy and gotten married," says Breedlove. She pauses before punctuating the thought with a "wow." But that thought, she continues, is now just "a fantasy."

Overall, she says people have been supportive. Old classmates from high school take her to doctor's appointments.

She says she had a negative experience with a doctor while being treated for a burn. The only other time she's experienced anything negative was when her cancer treatment coordinator referred to her as "he." The coordinator was embarrassed after Breedlove corrected her.

"It's actually OK," Breedlove responded. "It's taken me 65 years to get it right." ♦