Sixty years ago, the political landscape in the U.S. was drastically different than it is now. Instead of acting solely along party lines, lawmakers worked together, often across the aisle, to find bipartisan solutions.

And while the polarization we’re seeing in national politics today has always been present in some form, it didn’t take firm hold until 1994 when the GOP gained 54 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives — in what was called the “Republican Revolution.”

The charge was led by then-U.S. Rep. Newt Gingrich, and resulted in Eastern Washington’s Tom Foley — the first and so far only Washington state representative to lead the U.S. House as speaker — becoming the first House speaker since 1862 to lose a re-election campaign.

When Foley took office in 1965, he was a Democrat in a district that had elected Republicans for more than 20 years. After 15 terms — nearly 30 years — he lost his bid for re-election against George Nethercutt and the district again turned red. It’s stayed that way since, with U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers succeeding Nethercutt in 2005.

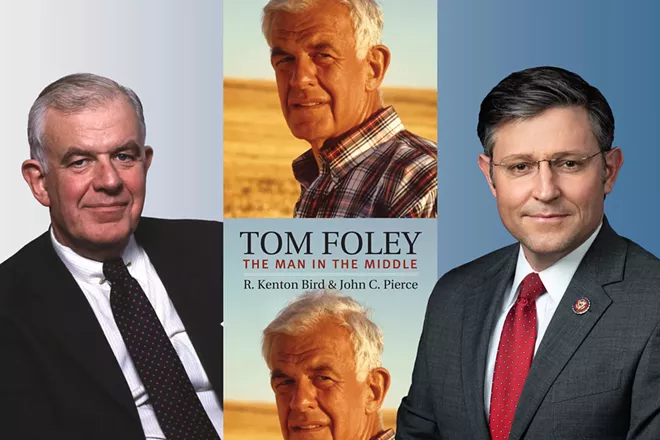

R. Kenton Bird and John Pierce set out to tell Foley’s political story in Tom Foley: The Man in the Middle, which was published in June. The Inlander spoke with Bird about Foley’s 30-year career in U.S. politics, the hyper-polarization of national politics after he was ousted from Congress in 1994, and what Foley could teach today’s politicians.

INLANDER: Why did you and co-author John Pierce write this book?

BIRD: The story actually begins more than 50 years ago, when John Pierce was a young political scientist. He won a congressional fellowship and worked on Capitol Hill where he spent half the year in the office of Frank Church, then a senator from Idaho, and the other half in Tom Foley’s office. So he had a real early chance to observe Tom Foley when he was still pretty much a junior congressman in the House.

Then, 15 years later, in 1988-89, I worked on Capitol Hill in the same program. The American Political Science Association had a congressional fellowship program for journalists to help them better understand the workings of what was happening on Capitol Hill. So that was what really piqued my interest in Congress.

I went back to the [Moscow Idahonian now known as the Moscow-Pullman Daily News] after the fellowship ended in 1989, but at that point I was ready for something else. So I enrolled in graduate school at Washington State University in Pullman in the Ph.D. program and American Studies, which brought together American history, American politics and American culture. The tipping point that led to my choice of further research on Foley was the 1994 election, when Foley was defeated by George Nethercutt and lost his seat after 30 years, in what was the so-called Republican takeover of the House of Representatives under the leadership of Newt Gingrich.

I ended up spending 1994-99 doing research on Foley’s congressional career for my Ph.D. dissertation. My dissertation was a fairly narrow profile of Tom Foley as a member of Congress, and the title was “The Speaker from Spokane: The Rise and Fall of Tom Foley as a congressional leader.” And then I set the dissertation aside.

I didn’t really think much about Foley until he passed away in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 18, 2013. I spent so much time immersing myself in Foley’s life and career, so I went to the memorial service that was held at St. Aloysius Church on the Gonzaga campus, and I saw a number of Foley’s close friends, political allies, former members of Congress who had served with him, and that got me thinking that there might be more to the Tom Foley story.

Why is Foley’s story important to tell now?

We saw Foley as an important transitional figure in the House of Representatives. He was the last of a long line of Democratic speakers that dated back to the 1950s. So it’s sort of this tipping point from a long line of Democrats to this shorter series of Republicans who had leadership positions.

Foley was a moderate ideologically, and one of the reasons he was successful as a leader in the House of Representatives was his ability to reach across the aisle to work closely with Republicans, as well as to bridge the big gaps in his own party between rural Democrats. Foley was able to bring them together with a gentle, persuasive style. He also had a backbone — he could be tough when he needed to.

He helped people find common ground to work together for the national interest. So that was one reason why we came up with the subtitle for the book — The Man in the Middle. He was in the middle chronologically as this sort of transitional figure. He was in the middle politically, because of his ability to be conciliatory, to create consensus when necessary. And when he couldn’t get consensus, he was able to push legislation through without creating a lot of animosity with the people who did not support that particular piece of legislation.

Foley took office in 1989 when George H.W. Bush was president, so for the first three years of his speakership he was working with a Republican president. Then when Bill Clinton was elected in 1992, the last two years of Foley’s speakership was spent working with a Democratic president. So I think it’s a good case study of a period in American politics when elected leaders of different parties could perhaps set aside their partisan interest to do what was good for the country, like the assault weapons ban, which was passed, at Foley’s urging after the mass shooting at Fairchild Air Force Base that year [when a former Air Force member shot and killed four people and injured 22 others on June 20, 1994].

You know, I can’t help but think that if the assault weapons ban did not have a sunset clause — it essentially expired after 10 years — that we might have avoided some of the bloodshed from the large number of horrible shootings we've had in this country.

Would Foley’s politics have changed if he was re-elected and served in the newly Republican-led House?

I think it was a blessing in disguise. Foley would not have been happy in that minority role if the Republicans were going to take control of the House. When you’re in the minority and a more partisan environment, you’ve got to be pretty aggressive and pretty partisan to get your message out — I don’t think Foley would have been comfortable in that role. Foley took great comfort in knowing that even in defeat, he diligently carried his home county of Spokane.

Do you think this hyper-polarization in national politics really got started after Foley was ousted from Congress in 1994?

Well, that was a watershed election because Gingrich successfully nationalized the elections for the House of Representatives. What Gingrich succeeded in doing was to make the 1994 election a referendum on Bill Clinton, who had been elected two years earlier. The party in power always loses seats in the midyear election, and that trend was already working against Clinton and the Democrats in Congress. But, Gingrich really succeeded in convincing people in places like Eastern Washington that they could tell Clinton to back off on his more ambitious policies by electing Republicans to the House — and it was successful.

Gingrich’s strategy, in part, was to attack the integrity of Congress and portray it as a corrupt institution because the Democrats had been in control of the House since the 1950s. This strategy was the only way to clean up Congress and get rid of the Democrats. It meant a lot of good people, like Foley, were tossed out, not because they themselves were corrupt, but because they were painted with that broad brush that Gingrich and his allies used in 1994.

It turned out it didn’t make a lot of difference to the reputation of the institution or the integrity of Congress’ and Gingrich later left the speakership after a book scandal that, in some ways, was very similar to the scandal that led to Jim Wright’s resignation in 1989. [Wright’s resignation essentially opened the door for Foley to become House speaker.]

So there wasn't a great deal of difference in how Congress was run after the Republicans came in, but I see 1994 as the beginning of the intense polarization, particularly in the House of Representatives, and to a lesser extent, in the Senate.

Do you see an end to this polarization anytime soon?

There were a couple of bright spots in the last month with the impasse over who the Republicans would nominate to be the next speaker after Kevin McCarthy. [McCarthy was voted out by fellow Republicans, the first time a speaker has been removed during a legislative session.] Minority Leader Rep. Hakeem Jeffries has also proposed what I thought were some very common sense changes to the rules of the House that would make it possible to work together across party lines.

One of the rules that he proposed was to repeal the so-called “Hastert Rule.” Dennis Hastert was a Republican from Illinois who followed Gingrich as speaker, and when he was speaker the Republican caucus passed a rule that said unless a bill had majority support within the leading party, it wouldn’t go to the floor — even if it would’ve been supported by a majority of the congressional body. So now, it’s practically impossible to do any bipartisan legislating.

If the Republicans had not been able to agree on a candidate for speaker [which they ultimately did last week], I thought, well, maybe the Republicans would choose a moderate that the Democrats could support for speaker. This would enable a little bit more conciliatory approaches to dealing with issues like climate change, and the budget and the war in Ukraine, instead of this very divisive approach that has been enforced since Republicans won back the House in 2022.

And maybe if the Republicans have to go through this speaker selection process again, there may be a window to have more conversations. I’m not putting a lot of money on the current speaker to be in office for a long time. There’s lots of speculation about whether the new speaker will be able to hold together the coalition that elected him in the wake of the two other candidates falling short.

There’s actually a group called the Problem Solvers Caucus that has an equal number of Republicans and Democrats that meet for dialogue. They’ve been at least having conversations and trying to find each other’s positions on issues and identify ways to cooperate. So I wouldn’t say that the picture is all doom and gloom.

Do you see any comparisons between Foley and today’s House Speaker Mike Johnson?

That might be a stretch.

What Mike Johnson has going for him is that he’s apparently a likable guy who is pretty congenial. He may not be well known, but those who have worked with him see him as able to do more persuasion with incentives and gentle arm-twisting, rather than then making threats. So that would be something where Foley, I think, would appreciate Johnson’s style.

We’ll probably see in the next two weeks the degree to which Johnson can use more gentle persuasion to get his fellow Republicans to pass a short-term spending measure to keep the government open.

Do you think any politicians like Foley even exist in today’s Congress?

Well, I have a friend who is a former Republican congressman from South Carolina. Former Rep. Bob Inglis was a freshman in the House in Foley’s last term as a speaker, and he is the leader of a group called republicEn. He is a climate change activist who is working hard to bring Republicans together on climate change issues and since leaving Congress, he has been working tirelessly.

I have the highest respect for Inglis and his approach because he’s doing what Foley used to do. He’s meeting people where they are and trying to find what it would take to get them to move just a little bit, one way or the other, so that they can come together.

I really like Jeffries. He’s obviously in a different role than Rep. Nancy Pelosi, because Pelosi had the big challenge of being the Democratic speaker in a time when Donald Trump was president. But, I think he’s being thoughtful and articulate and in a different environment he could be the kind of speaker that Foley was.

Just in the state of Washington, you're gonna find more moderate candidates and members of Congress who are going to be less partisan and may be more receptive to the kinds of compromises that were more common in the late ’80s, early ’90s.

Is there a possibility that someone like Foley could retake office in the district he served 30 years ago?

The interesting thing about the 5th Congressional District of Washington is that it has pretty much had the same configuration since 1970. While the boundaries have been the same, the economy of the district has changed significantly. Jobs in 1964 were in agriculture, forestry, mining and more natural resource oriented. Today, the jobs are in commerce and finance and health care and to a lesser degree in high tech. That has posed challenges for Democratic candidates ever since Foley lost in 1994. Nethercutt had five terms, 10 years, and Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers has held the seat since then.

I don't see any scenario where the Democrats are going to recapture the district until she retires. If it's an open seat and there are some fresh faces running, a strong, moderate Democrat might be able to win the seat.

Is there anything about Foley that may not have made it into the book but is still important to understand his role in U.S. politics?

So I found Tom Foley to be a fascinating figure, but also somewhat of an enigma. He didn't have a lot of close friends in Washington, D.C., I think he probably maintained more close friendships in Spokane, even when he became the speaker. One of my regrets is that between the time I did my dissertation in the late ‘90s and when we started the book together in 2019, that a lot of his confidants and close friends had died.

He had a cousin that had been in law practice in Spokane, another lawyer had been his longtime campaign manager, a former federal judge in Spokane, people that he had grown up with or had gone to law school with, so what was missing from the book were those personal anecdotes from people who knew him best. We didn't really get that kind of personal glimpse into what made him tick. We relied predominantly on what was on the public record.

Foley was such a great storyteller. The stories about him and the stories he told have taken on new dimensions in their retelling. We have a story early in the book about Foley at the Omak Stampede — the big rodeo in North Central Washington — when Okanogan County was part of the Fifth District. Foley ended up on a horse for the grand parade at the rodeo and his horse was not taking directions very well and ended up going the opposite direction from the rest of the parade. The other dignitaries already left the arena and then there's Foley by himself in the middle of the arena with his cowboy hat and difficult to control rodeo horse. That story sort of defined Foley's early years and his willingness to get out and meet people where they were. He never really lost touch with the people of the constituencies that he represented. ♦