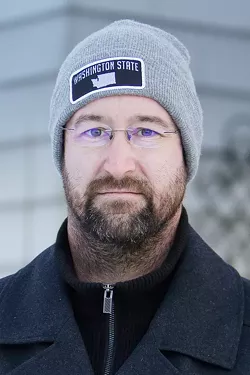

JUSTIN JAMES SHERFEY

INVESTOR/FLIPPER

When he was 19 and going to school at Eastern Washington University, Justin James Sherfey listened to a lot of podcasts about the housing market. Real estate offered the appeal of financial freedom and the ability to take time off when you want, so he decided to jump right into the business of renovating homes and reselling them.

Through family who work in real estate and construction and his own research, he learned how to find potential "contract flips," where he'd locate a property, help negotiate a deal and pass the baton to an investor who could fix it up.

The type of properties he looked for had often become untenable for owners to keep up. Some people fell into pre-foreclosure status after missing payments. Other properties suffered damage from tenants, and the owner wasn't able to afford repairs. In other cases still, people inherited property they couldn't maintain or clean up (say, if it had been hoarded).

Now 23, Sherfey chips in with partners to purchase properties to fix and sell, or rent out.

"Over the last couple years post-COVID [arriving], inventory has shot down to all-time lows," Sherfey says. "The housing market is just crazy."

He knows house flippers sometimes get a bad rap, but he hopes people know he and his partners work with owners and whoever is living in a home to help them find a solution to their situation. They never kick people out without a place to go.

"We're really trying to do right by people in the situations they're in. We know we're not a fit for 99 percent of sellers out there, and we realize that," Sherfey says. "But if we're able to help someone not have a bankruptcy or foreclosure on their record, we're going to pursue it."

KEITH KELLEY

LANDLORD

Keith Kelley says he was the only landlord on the city of Spokane's affordable housing committee. And he says he kept getting the same kinds of comments: "Keith, if you go out of business, your family's going to be just fine."

And in one sense, that's true.

"I'll adapt and find other work," Kelley says. "My family will be fine. But what happens to the roughly 75 people that I provide affordable housing to?"

That was the crux of the tension with Washington state's eviction moratorium last year. Of course protecting low-income tenants from becoming homeless is more compelling than a landlord's bottom line. But if you make it so miserable that landlords don't want to be in the low-income rental business, you'll have fewer available homes to rent, and the rent will be pricier because of it. Drive out decent landlords, he argues, and all you'll be left with will be the bad ones.

"The policy environment has created a host of unintended consequences," Kelley says. "I don't think anyone intends to make life absolutely miserable for our marginalized communities."

He says challenges he faced dealing with dangerous and destructive tenants during the eviction moratorium — and the spate of new laws intended to protect tenants — is pushing him out of the business.

He's already sold most of his shared single-room occupancy rental houses, and he's planning on selling his multifamily properties as well, though he hasn't made a final decision yet.

In his case, he's been trying to make sure to find buyers who will continue to offer them as affordable rentals. But that's not been the case for every landlord. He says he knows of another landlord in West Central who's converting five of his rentals into Airbnb-style short-term rentals. That risks making Spokane's affordable housing crisis worse.

Kelley isn't sure about what he's going to do next. He says he thought about investing in other cities but says he didn't get into this business just to make money.

"I am passionate about Spokane; I'm passionate about affordable housing," Kelley says. "[But] I can't live out my passion and get beat up all the time."

MARCY MARTIN

REALTOR

Marcy Martin never thought the Spokane housing market would get this crazy.

Martin has been working as a Realtor in Spokane for around 15 years. Over the course of the pandemic, she's watched as a rise in remote work and buyers from major cities across the country transformed Spokane's real estate market.

"It's pretty stunning growth," Martin says. "Two years ago you definitely had a lot more wiggle room."

The market has become especially tough for first-time homebuyers aiming for houses in the $300,000 range. The market is competitive, and cash offers are increasingly common, Martin says. For first-time buyers, moving quickly is key.

"We have to get in the house that day if it comes on the market," Martin says.

Martin doesn't see the Spokane market slowing down anytime soon. More people are realizing their jobs can be done from anywhere, and even with prices skyrocketing, Spokane is still a cheap alternative to cities like Portland and Seattle. One of Martin's clients was able to buy a 7,000-square-foot home in Spokane using cash from the sale of his home in Los Angeles — a 400-square-foot property (picture a two-car garage) that went for just over a million dollars.

ZOE HJELM

DIVERSION SPECIALIST

In her work at SNAP (Spokane Neighborhood Action Partners), Zoe Hjelm is familiar with how difficult it is to help people get off the street and into housing.

Through "coordinated entry" applications, social service agencies in Spokane first rank the many difficulties people face (mental health, addiction, medical issues, etc.) to figure out if they qualify for help.

For those with fewer struggles, rapid rehousing is an option. If they can find an apartment, there's money to cover early costs and the first few months of rent so people can move in, start working and take over payments on their own.

For those with higher needs, there's permanent supportive housing operated by a provider such as Catholic Charities. Those apartments are meant to build the skills and rental history needed to later move to other housing options.

But the system has been overwhelmed in recent years, both as the number of vacancies in Spokane has plummeted and the number of high-needs people has increased, Hjelm says. Some higher-needs people would actually qualify for assisted living, but many don't want to go that route, she says.

"What we have noticed is kind of a twofold problem: The folks that are coming through coordinated entry are higher acuity, with mental health, substance use issues, evictions, domestic violence, a plethora of issues, right?" Hjelm says. "And then there's a very, very limited number of apartments."

If someone can even find an open rental to apply for, when they have no job, no credit, and maybe an eviction or felony on their record, landlords don't even consider renting to them, even if they've got income to cover the rent, Hjelm says.

"It's just heartbreaking really. ... They come to our door and think we have apartments we can just put people in ... [then] they find out this is on them, and you see that look of defeat," Hjelm says. "There's less than a 0.4 percent vacancy rate. Even if everybody had the money, we wouldn't have enough places to go."

LT. ARIANA WILKINSON

RENTER

Back as an ROTC student at Texas State University, Air Force Lt. Ariana Wilkinson never had a problem finding an apartment to rent. So when she was sent to Fairchild Air Force Base, Wilkinson had no idea how difficult a problem simply finding a place to live would be.

Wilkinson had tried checking apartment listings only a couple times and assumed that things would open up when Gonzaga students left for the summer. Instead, by the time she got her active duty orders in July 2021, the apartment hunt was a nightmare.

"I realized that availability was really, really, slim," says Wilkinson, a public affairs officer at Fairchild. "This was one of the first big obstacles I had."

For nearly a month she searched, staying in hotels like the Hampton Inn as she scrambled to find a spot.

"I think I honestly applied to about 25 or 30 different apartments," Wilkinson says. "Spokane Valley, Spokane, Airway Heights, north side, South Hill, all locations."

And she wasn't the only one. Fairchild Air Force Base is a massive economic engine, generating over $520 million in economic impact a year in Spokane. But even their best efforts to find housing for their airmen faced serious obstacles last summer.

"It was really frustrating. You'd lose sleep over it," says Jack Farver, who works in Fairchild's Housing Referral Office. "We started driving anywhere and everywhere, looking for rentals that wouldn't be advertised, looking for duplexes or new apartment complexes."

They'd get ahold of the property managers and keep checking in: When might there be a vacancy? Things are slightly better now, but still pretty rough.

In Wilkinson's case, she ended up finding a townhouse condo. It was about timing. Within 30 minutes of a vacancy opening, she called the landlord, told her all about her situation, and said she was new to the area. The landlord seemed to understand.

"I was able to secure a condo on the South Hill," Wilkinson says.