A few pops of color dominate an otherwise drab conference room. A bright red sweatshirt broadcasts that "Housing is a Human Right." Pink hearts on a homemade sign finish the equation "Housing Stability = 🩷," while orange flowers on another sign dance around the words "Black Women 4 Housing Stability."

But all the sentiment in the room on Sprague Avenue can be summed up by just five words stenciled in purple: "Rent is too damn high."

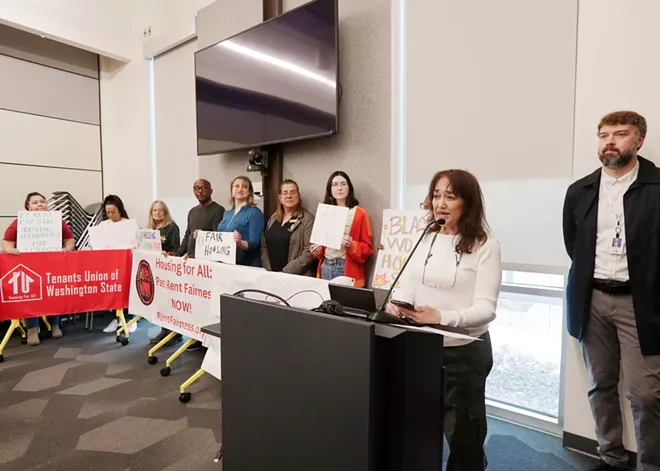

On April 3, advocates from the Tenants Union of Washington, The Way to Justice, Manzanita House and the Washington Low Income Housing Alliance hosted a tiny press conference at the Hive, a branch of the Spokane Public Library, to show their support for statewide rent stabilization.

Lawmakers in Olympia are currently considering the idea — again — via House Bill 1217 and its companion Senate Bill 5222.

About 40% of Washingtonians currently rent their homes, and they have "zero protections right now about how high their rent can go," says state Sen. Emily Alvarado, D-West Seattle, one of the main sponsors of the bill.

Rent stabilization is not a new idea. A similar bill died in the Senate last year, and the year before that. But despite its repeated defeats in the past, the current rent stabilization bill looks like it has its best shot yet of passing.

This session's bill is pretty stripped down compared to previous iterations after its sponsors made significant compromises to developers, Alvarado says. The proposed law would cap rent increases at 7% annually (or 5% for manufactured home lot rents) and require 90 days' notice before rent increases. The proposal does not include any caps on move-in fees, as previous efforts did, and exempts new construction that's less than 12 years old from the cap on rent increases.

"What's left is a basic bill that provides one simple iota of predictability for tenants — one small thing for tenants," Alvarado says.

Adopting rent stabilization would give an immediate sense of relief to some renters. But its long-term effects are less predictable.

Academics generally agree that rent control leads to fewer housing units overall, more poorly maintained buildings, and increased rents for anyone in a noncontrolled rental.

The Spokane Home Builders Association estimates that Spokane is short about 32,000 housing units, and argues that the shortage is one of the biggest factors driving up costs for renters and homeowners alike.

Washington builders also face construction costs that are outpacing inflation, skyrocketing interest rates on loans that are now sometimes in the double digits, more state fees than the national average, and insurance costs that have doubled within a few years.

"Everything I've read or understood about [rent control] has said that over the long term, it tends to dampen new construction," says Chris Venne, a semiretired senior housing developer for the affordable housing nonprofit Community Frameworks. "It tends to disincentivize landlords to do maintenance. And especially in Spokane, we have a situation where, if builders see a reason not to build here, they're just gonna go to Idaho. That's already happening in single-family home construction."

WHERE'S THE RELIEF?

"Twenty years ago, my life was really good," Tina Hammond tells the housing advocates and reporters gathered at the Hive.

Hammond is a 64-year-old Spokanite. She owns her home and has a master's degree from Gonzaga University. But her life changed a decade ago. She lost the home where she used to live in 2010 and developed debilitating arthritis. She spent years renting a basement or a mother-in-law suite from friends until she could buy a manufactured home with money her father bequeathed to her.

Hammond is now on a fixed income that's less than $2,000 a month. It used to barely cover her medicine and the lot rent for the land where her mobile home sits. But when her lot rent went up by $66 a month last year — a 12% increase for her — she says it meant that she had to pause her meds for three months to save the extra cash. She turns her heat off at night to save money — over the winter, she says, the temperature inside her home often fell below 45 degrees overnight.

Hammond fears the day her rent will increase again, quite possibly by far more than $66 a month. While rent stabilization wouldn't stop her rent from rising, it could replace her sense of dread with a sense of expectation — she could stop worrying and spend her energy planning ahead for a 5% increase.

Duaa-Rahemaah Hunter, a statewide organizer from the Washington Low Income Housing Alliance, stresses the difference between rent stabilization and rent control. Rent stabilization restricts the amount that a landlord can increase the rent of a specific tenant annually. If that tenant moves out, the landlord can readjust the rent by more than the cap and find a new tenant.

Rent control, on the other hand, is far more restrictive and caps the total amount that a landlord can charge for a specific apartment or unit. Advocates argue that rent stabilization doesn't cut profits like rent control does, but provides much needed relief and stability for tenants.

Terri Anderson, the interim executive director for the Tenants Union of Washington State, says that it's not uncommon for renters to face a $400 per month increase under the state's currently required 60-day notice. She says that the most common call to the Tenants Union crisis hotline is regarding an "economic eviction" — that is, being forced out of a home because of a near-immediate monthly increase that the renter can't afford.

From 2020 to 2023, Spokane's housing vacancy rate was below 3% — at times even below 1% for small apartments — which made it nearly impossible for someone to move into a more affordable apartment if they needed to.

National statistics also show that increases in rent are intimately connected with increases in homelessness. Research from the U.S. Government Accountability Office shows that a $100 increase in the median rent is associated with a 9% increase in homelessness.

"It's not 'people experiencing homelessness,' it's 'people who can't afford rent,'" Spokane City Council member Paul Dillon says.

According to the Washington Center for Real Estate Research, the average rent in Spokane has increased by $300 since 2019. But it's possible that more affordable rentals saw more significant increases — just ask Dave Bilsland, a retired veteran whose rent doubled from $525 a month to $1,050 a month in six years.

If a 7% cap had been in place since 2019, his current rent would be about $788 per month.

"This bill is about people," Alvarado says. "It's about elders who are sacrificing medicine, who are sacrificing heat in order to keep up with rising costs. It's about people like parents who just want their kids to be able to stay in the same school and not have to deal with 10%, 20%, 30% rent increases."

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

Research is very clear about one thing: Rent caps are very good at stabilizing rent for some renters.

But as for stabilizing the rest of the housing market? Current research says probably not.

The Journal of Housing Economics recently released an overview of all studies done on rent control across the world from 1967 to 2023. The review concluded that "although rent control appears to be very effective in achieving lower rents for families in controlled units ... it also results in a number of undesired effects, including, among others, higher rents for uncontrolled units, lower mobility and reduced residential construction."

That is, any rental unit without a rent cap — in Washington's case, any rental built in the last dozen years — typically becomes more expensive. Plus, people stay put for longer in rent-controlled apartments (as opposed to moving toward home ownership, which is the most stable housing situation to have), and developers build less housing.

The research aligns with the concerns of housing builders, who often oppose this type of legislation.

Isaiah Paine, public affairs and strategic officer for the Spokane Home Builders Association, says that pricing instability generally comes from a mismatch between housing supply and demand. New home construction has taken hit after hit, which has helped create the high prices Spokane faces today.

"It's death by a thousand cuts," Paine says. "Everything across the board has seen some increase."

The five main cost concerns for builders are nicely alliterative: land, labor, lumber, lending and laws. Each category has become more volatile in recent years, Paine says, and faces even more uncertainty as new tariffs throw everything into a tizzy.

As costs grow more unpredictable, developers look for safer profit margins. If costs keep rising but revenue from previous projects stays relatively stagnant, developers might choose to build in a cheaper location (read: Rathdrum or Post Falls) or not build at all.

Community Frameworks' Venne, who has spent nearly 30 years working to build affordable housing in Spokane, says the classic X-shaped supply and demand curves from microeconomics don't capture everything that's happening in the housing market, but it's not a bad place to start.

"Just saying 'It's supply and demand' is a little bit of oversimplification," Venne says. "But it is certainly an important factor."

While the proposed legislation centers on rent stabilization, both for-profit developers and nonprofit housing groups agree that the most stable living situation is home ownership, much to the frustration of millennials.

According to the literature, when rent caps disrupt revenue streams and market activity, they decrease the development of all types of new housing. That means a rental cap could decrease the availability of starter homes for people trying to move away from renting altogether, Paine says. Buying a home can seem nearly impossible for most people in their 30s, and in Spokane, it practically is.

"Only 15% of Spokane residents can afford to purchase a new home, and so essentially, the only people who can afford to purchase a home are the people who already own a home," Paine says. "That's not a long-term reality that we want for our community."

Spokane is missing lots of "middle housing" units, which are what developers typically call the small homes or townhomes that people typically buy to move away from renting and up the housing ladder.

But Venne wonders if the housing situation in Spokane might be turning a corner.

Spokane's vacancy rate has risen to 5.5%, which is close to an equilibrium rate where there's no positive or negative pressure on the market. Paine says that 3,000 housing units are planned to become available in the next year to 18 months. Dillon mentions the relaxed rules that Spokane has put in place locally to allow more freedom for multifamily housing units.

"Although people are scared of rent increases, and they certainly have happened, I think the market has changed to some degree," Venne says. "This may be an issue that people are looking in their rearview mirror and reacting to the way the world was three years ago, not the way it is now." ♦