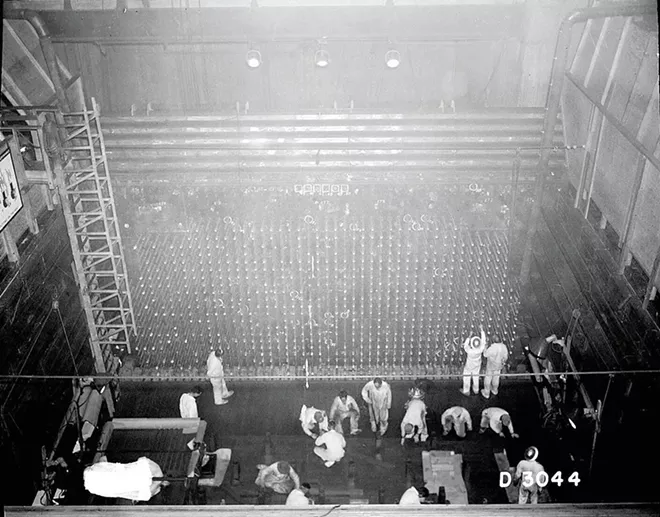

The B Reactor at Hanford was the nation's first industrial-scale nuclear reactor. It brought us the atomic bomb — in fact, it produced the plutonium for the first atomic test blast, Trinity, and the bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki. It left us with a legacy of scientific and technical advances as well as moral debates that will be with us for centuries, to say nothing of the colossal environmental consequences we'll be dealing with for millennia.

Late last year, Hanford's B Reactor became part of the Manhattan Project National Historic Park, which consists of three sites: Hanford in Washington, Oak Ridge in Tennessee and Los Alamos in New Mexico. You can tour Hanford today, and it's tempting to see its story as mostly an epic engineering tale.

But there's more, so let's hope the diverse human history of Hanford doesn't get overwhelmed. It's a tale that involves the Native Americans whose land it was built on — viewed by New Deal planners during the Depression as the "land of abandoned hopes," according to historian Michele Stenehjem Gerber in her excellent Hanford history, On The Home Front. Native Americans also were impacted by atomic tests and uranium mining in the Southwest. And of course there are the Japanese who were the first bomb's victims.

There are also the stories of the residents of rural communities who were displaced by the secretive project — who didn't know why the government had removed them from their land until the day the bomb was dropped in 1945. There are the scientists and engineers, the farmers, and the "downwinders" who suffered subsequently from the site's toxic elements released into the atmosphere.

There are the families who grew up nearby. One of those was the family of poet Kathleen Flenniken, who was raised in Richland and whose book, Plume, is a meditation on life in a nuclear site. She says families like hers (her dad was a Hanford civil engineer) lived as if they were members of a "secret society" where hazards were undisclosed, work could not be divulged even to loved ones, and where people were encouraged to have faith that something good and necessary was being done. "You were loyal to something you did not understand," she says. Think of a Mad Men-era nuclear cult in the desert.

An interesting exhibit called "The Atomic Frontier: Black Life at Hanford" recently brought a little-known slice of Hanford's human story to life at Seattle's Northwest African American Museum. Vast numbers of workers were shipped into the then-remote desert to build and run the B Reactor. That included thousands of African Americans eager to escape the Jim Crow South and get decent jobs during the wartime labor shortage. About 5,000 — roughly 10 percent of the Hanford workforce — were black, according to Atomicheritage.org. Some 15,000 African Americans moved to the area for the duration.

Blacks did construction and service jobs. They were janitors, waitresses and drivers. For the most part, they were banned from local restaurants and targeted by the local Pasco police. Still, they were, at least for a time, partially free of the limits they faced down South.

Mess halls were integrated, even if the barracks and many social events were not. Hanford maintained a weekly calendar of events — plays, dances, concerts, etc. — for Manhattan Project workers trapped in the middle of a dusty nowhere. A large wartime calendar on display in the exhibit was divided into "White" and "Colored" categories — startling to see for those who think such things did not happen in the Pacific Northwest. According to Atomicheritage, "Lula Mae Little, a waitress who worked at the mess hall, referred to Hanford as the 'Mississippi of the North.'"

It's startling to see a World War II propaganda poster in the exhibit that features a white and black worker side by side — an indication of how necessary blacks were seen as being to the war effort, and clearly an attempt to make whites understand that working with them was their patriotic duty. That attitude did not survive the war's end. Governor Art Langlie stated his preference that workers brought into the state for the war be sent back to where they came from, and Hanford hired no blacks as permanent workers in the wake of the war.

Some stayed in the Tri-Cities. Others dispersed, but not necessarily back "home." After the war, many black workers moved to find jobs elsewhere, especially in coastal cities like Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles. That postwar boom changed the race dynamics of Seattle.

"World War II brought a lot of folks to this part of the country," says exhibit curator Jackie Peterson, a museum consultant from New York. She has seen the power of telling more inclusive histories at major sites, like the Presidio in San Francisco, which touches on Native American, Hispanic and African American history, ranging from the original residents on San Francisco Bay to the Buffalo Soldiers, those black cavalrymen who passed through en route to protect parks like Yosemite and Sequoia.

There are big advantages to working hard to be inclusive, she says, to "go out of your way to where everyone sees themselves" in the story.

That's a message the Park Service should seize upon in telling the big history of Hanford's B Reactor. ♦

A version of this article first appeared on Crosscut.com.