The first advertisement a shopper notices when entering Coeur d'Alene's Silver Lake Mall isn't one for spring fashion or Cinnabon. It's the one painted across an entire wall in big, brash deep red, telling shoppers to go to college.

"CARDINAL RED LOOKS GREAT ON YOU!" the ad proclaims, with the North Idaho College cardinal mascot peeking out. "Apply now at www.nic.edu/Apply."

Nearby, in a bright pink Payless ShoeSource aisle, Geoffrey Hess says he actually did apply to North Idaho College, back in 2013. "I had the acceptance letters, I had taken the [ACT] Compass test, had everything squared away," he says. But then his parents kicked him out their house: "I didn't have access to the Internet. I ended up living out of my vehicle."

In the chaos, he missed his financial aid deadline. Instead of school, he ended up working odd jobs, mostly manual labor, often getting paid under the table.

His friend next to him didn't make it to college either. Damian Johnson, decked out in a camo sweatshirt, planned to take just a year off after high school before college. But one year became five. Five years of bagging groceries, pushing shopping carts and manning gas station registers. "It's been rough," he says.

The reasons for missing out on college vary. Just ask the people in this one mall: The employee at the body-piercing parlor says her mom refused to fill out her financial aid information. The young woman walking through the mall arm in arm with her boyfriend says a mental health diagnosis nixed her culinary school plans. The tattooed dad, eating at the food court with his two little blonde girls, says his first daughter was born before high school graduation and work made more sense than college.

Jon Byrum, 25, and his wife, Paris, look through the window of a jewelry store. "Never saw the point of it," Jon says of college. High school, he felt, had mostly been a waste of time. Why would college be any different?

"I didn't know what I wanted to do," he says. "So why go to college, get my general education, get all that nonsense, so I can have an A.A., which means absolutely nothing, and still not know what I'm doing?"

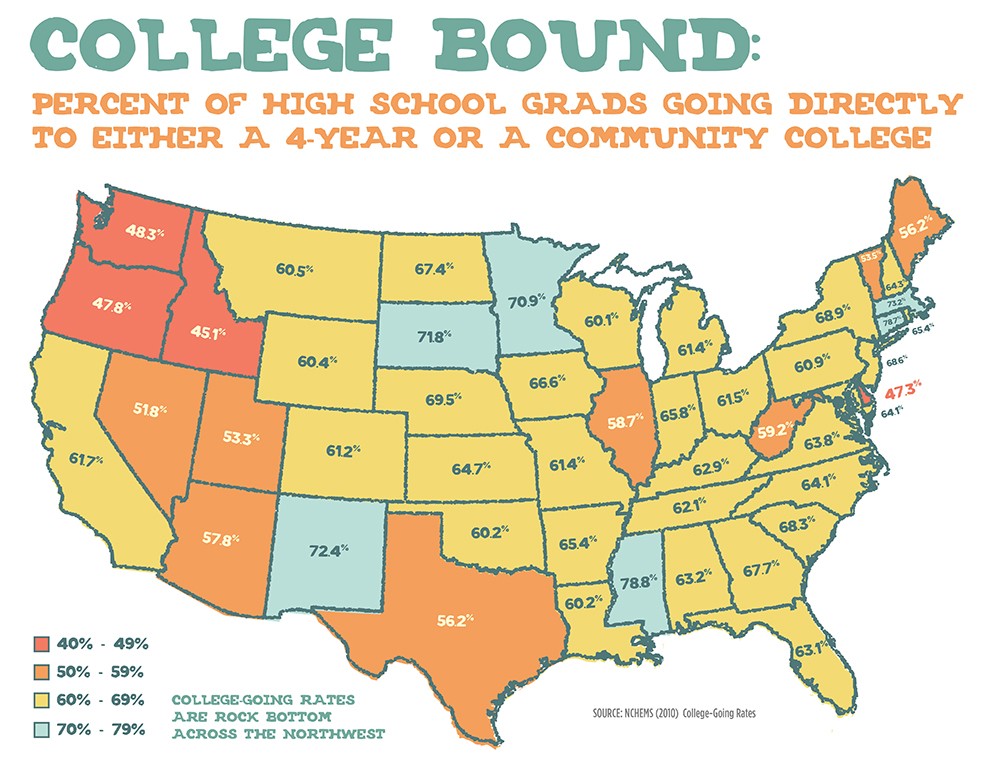

Add all of these reasons together, zoom out, and you've got a problem that plagues most Western states, but especially Idaho. A year after high school, nearly half of Idaho's 2013 high school graduates hadn't enrolled in higher ed. In 2010, Idaho ranked last in the nation in its college-going rate, and it's remained in the bottom five ever since.

You can quibble about the data — some measurements don't account for military service, apprenticeships or Mormons who do door-to-door missions after high school — but it all points toward the same grim conclusion: As Idaho's economy is struggling, its high-tech jobs are going unfilled and the solution — an educated workforce — means that a lot more Idahoans need to start getting college degrees.

Idaho knows this: Since 2013, the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Foundation has been pumping out ads calling out the dismal state of Idaho education.

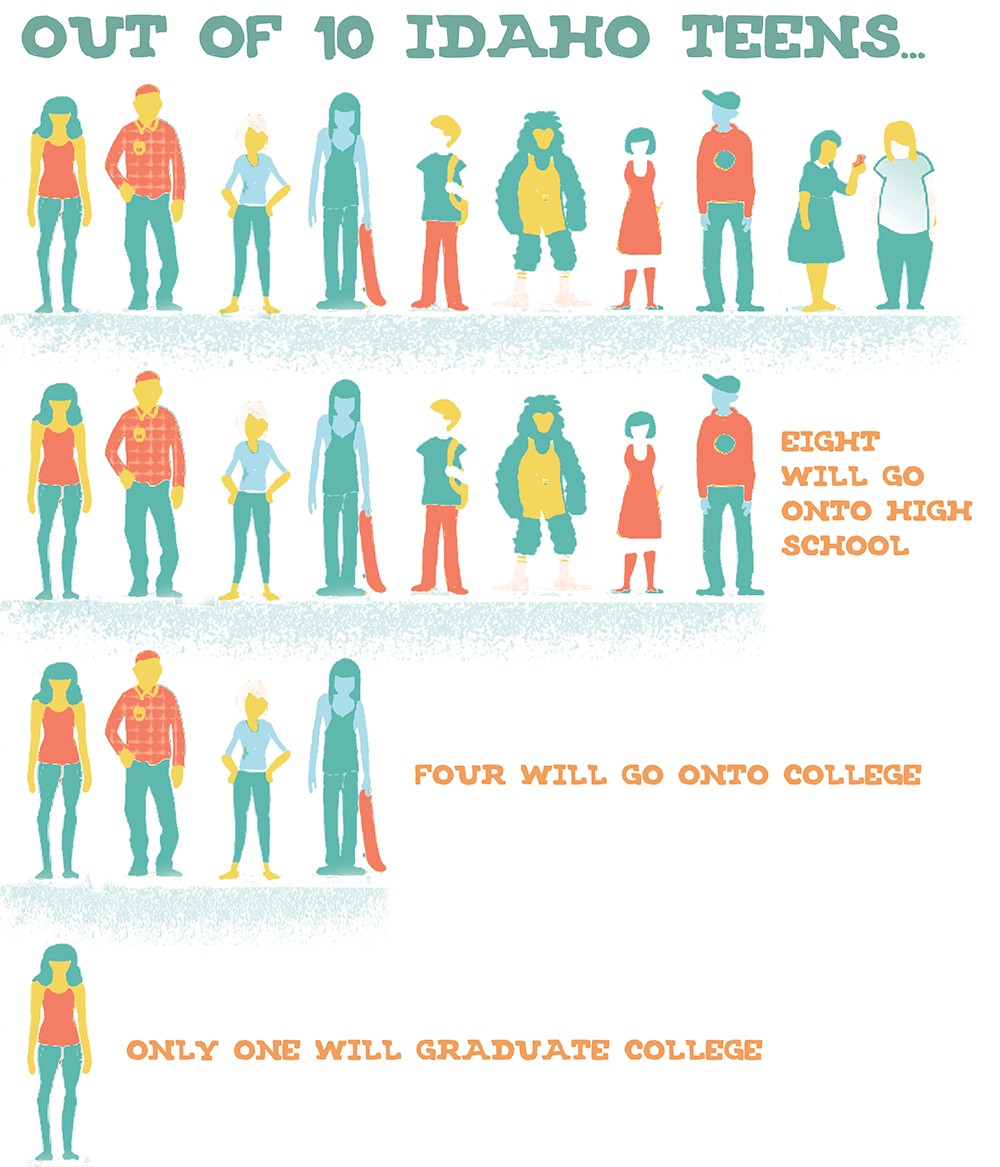

"Look at it this way: For every 10 high school freshmen, eight will graduate, four will go to college, and only one will graduate with a degree," former Dirty Jobs host Mike Rowe narrates in warm, earnest tones in one ad. "Let's get to an educated state. Don't Fail Idaho."

The foundation had tried positive ads. For five years, it ran an $11 million "Go On" campaign encouraging students to go to college. They didn't work. Districts, universities, business leaders and legislators have banded together to fight the problem, but after rising briefly, the statewide rate of kids going to college actually declined from 2013 to 2014.

"It alarms me that people aren't more alarmed by this," says Jennie Sue Weltner, foundation spokeswoman. "We're not making the kind of progress everyone hoped we would make."

The question is why.

The Isolated Geography

It was 11 degrees below zero in Pocatello, researcher Jered Hinchcliffe recalls, when he flew into Idaho in December of 2013. Over nearly two weeks, he visited Pocatello, Coeur d'Alene, Boise and Twin Falls. He looked everywhere: leadership classes, malls, a bowling alley, a Boys and Girls Club, a KFC and a Carl's Jr.

He'd been hired by the Albertson Foundation's ad agency to find kids to talk about their plans after high school.

"One of the things we noticed the most, especially for the younger people, is that they all had a plan," says Hinchcliffe. "They all wanted to go to college." But the closer they were to graduation, he says, the less certain and more skeptical they had become.

Brand strategist Jen van Arkel and her colleague followed up with in-depth interviews, the entire thing filmed by a documentary crew. All this to ask: "Why don't more kids go on to college after high school?"

The kids shared their fatigue and frustration with school, the lack of support they felt and the mixed messages they've heard about the value of college. And as she interviewed them, she saw the dramatic disparity between kids with bright academic futures and kids with dim ones. Income mattered. Day-to-day struggles like paying rent or avoiding domestic violence can make higher education the last thing on their parents' minds. Location mattered too.

"We talk to some kids in more rural areas whose families are in agriculture, and they would say, 'My dad didn't go to college, and my grandfather didn't go to college, and they're doing just fine,'" van Arkel says. "So why bother?"

These are places like Bonners Ferry, a town of less than 2,500 near the Canadian border with the lowest per-capita income in North Idaho. A year after 2013's high school graduation, only 41 percent of Boundary County students enrolled in college, one of the lowest rates in the state.

"A fair amount of that is probably just financial hardship and difficulties," says Tim Gering, principal of Bonners Ferry High School. "This is a very economically depressed area."

As a rule of thumb, poor, rural communities struggle to send their kids to college: Nationally, a National Student Clearinghouse study of the class of 2013 showed high-income suburban high schools had college enrollment rates nearly 50 percent higher than low-income rural schools.

Idaho is especially rural and poor. Legislators cringed last year as the Idaho Department of Labor reeled off 2012's economic rankings. Idaho: last in the nation in average wages, per-capita income and wage increases; first in percentage of minimum-wage workers.

The pothole-pocked roads and isolated communities in Idaho can hit education hard. For the more than 400,000 Idahoans living rurally, it's easy for college to seem out of reach.

Take Chad Copenbarger, for example, a recent high school grad from Wendell, north of Twin Falls.

"I did go to college for two weeks and had enough of that," Copenbarger says. During those two weeks, he had to juggle classes, work and the distance between. He drove his used Chevy pickup from his jack-of-all-trades job in the city of Wendell a half-hour to the College of Southern Idaho, and then the half-hour back.

"I liked the class. I liked to learn how to weld," Copenbarger says. But gas alone, he estimated, was costing him $100 every month: "I couldn't make what I was spending." So for now, he's dropped his college plans.

Idaho, filled with federal lands, has very few colleges. In fact, for most of its history there were only two comprehensive community colleges in the entire state. Until 2009, even Boise didn't have one. (Idaho actually is in the middle of the pack in sending students to four-year colleges — it's community-college attendance where Idaho's in dire straits. )

A look at state data shows that isolation and poverty are hardly the whole story, however. Chart Idaho's "go-on rates" by how well schools are funded, or by the poverty level, and the result looks like a shotgun spread. No obvious correlation. There's another factor at play, something elusive to define and unique to each community: culture.

The Self-Reliance Doctrine

Matt Handelman, superintendent of Coeur d'Alene Public Schools, says when he moved to Idaho from Spokane a few years ago, "the fierce independence of Idahoans" stood out, with their sense of "don't tell me my life's trajectory."

"There's less of a sense of the importance of education for education sake's as much as other places I've lived," Handelman says. "Early on, people I met here preached that you're throwing away money by just going to a four-year liberal arts school."

If you're not exactly sure what you want to do, he says, the sense in Idaho is that you're just piling on debt. Instead of seeing college as an exercise in intellectual edification, Handelman says many Idahoans view it in practical terms: Is it worth it?

In the long run, studies still suggest that it is. An associate's degree results in annual salaries more than $6,500 higher than just a high school diploma, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Georgetown University research finds that recent college graduates were making more than even employees with decades of experience and only a high school diploma. Even art and psychology majors made nearly 30 percent more than their non-college peers. (Engineering majors? 138 percent higher.)

Yet the case for college has become more muddled lately, partly a victim of its own success. At one time, an applicant with a bachelor's degree stood out from the crowd. Now, they're competing with a horde of peers holding degrees just like theirs.

Combine that with exploding tuition — 30 percent higher at University of Idaho and Boise State University than in 2008. "Kids are hearing their peers getting saddled with a ridiculous amount of debt," van Arkel says.

For the seven years she's been a postsecondary transition counselor at Sandpoint High School, Jeralyn Mire has watched students struggle with the decision to go to college. Facing uncertainty over what they want to be and the huge price tag, many choose what seems like a sensible option: Take a year off and work. Then, once they've saved up, go to college. An improving economy, where entry-level jobs are becoming more available, can make that path seem even more attractive.

"Until they get a truck payment. Until they get a cellphone bill. Until they get a girlfriend. Until they get a boyfriend. ... and they have no money," Mire says. "Life happens. And it gets harder." She pleads with students to keep at least a toe dipped in education.

Pell Grants and scholarships are available to help with financing, especially for low-income parents. But that's only if they know how to get them. One report estimates that nearly $20 million in financial aid went unclaimed in Idaho in 2013.

The FAFSA form for federal financial aid has 108 questions, and one 2007 Brookings Institution study calculated that completing it took 10 hours on average. For parents who've never been to college, taking that on can be especially intimidating.

"You want me pissed off?" Mire asks, then rattles off a story about a bright kid losing a scholarship from Boise State University because he won another scholarship from a regional foundation. She's yelling, swinging her hands.

"There you go! Here, kid! Go apply, go do some work, bring in an extra scholarship! Oh, we're going to take yours away! Because we've met your" — she shifts into a mocking tone — "federal need."

Mire helped the family get the issue resolved. But many parents don't have someone like Mire to guide them through the process, while others are downright skeptical of what college represents.

"Education has a reputation, straight up into higher ed, for being a bastion of liberalism," Handelman says. "Bastions of liberalism aren't received too well in Idaho." In 2012, for example, the Coeur d'Alene School Board ended the International Baccalaureate program after two years of the program being attacked for allegedly having a liberal, United Nations-backed agenda.

So why would Idahoans want to spend tens of thousands of dollars to send their kids to a place that contradicts their values?

To some conservatives, like the Idaho Freedom Foundation's Wayne Hoffman, all this obsession with college has a dark side.

"It's causing people to emphasize college to everyone, people that don't need to go to college," Hoffman says. He's worried about "credentialism," the idea that the letters of a degree matter more to society than the training it represents, that employers may be turning down qualified applicants because of educational requirements. Degrees, critics worry, can just as easily be artificial barriers, perpetuating inequality, as they can be signs of expertise.

Last month, the credentialism debate invaded the 2016 presidential race as pundits wondered whether — despite being the governor of Wisconsin — potential GOP candidate Scott Walker's lack of a college degree disqualified him from the presidency. Rowe, who voiced "Don't Fail Idaho" ads, leapt to Walker's defense.

"I think a trillion dollars of student loans and a massive skills gap are precisely what happens to a society that actively promotes one form of education as the best course for the most people," Rowe wrote on Facebook. "And I think that making elected office contingent on a college degree is maybe the worst idea I've ever heard."

Many of the Idahoans fighting to improve college-going rates would agree. College, in the classic four-year sense, isn't for everyone. Van Arkel worries that society's focus on the four-year degree is so unrelenting, it drowns out the other options — community colleges, trade schools, apprenticeship programs.

It's why they've shifted from the phrase "college" — implying four-years, ivy-covered dorms and tweed-jacketed professors — to "postsecondary," alluding to community colleges, trade schools, the military and apprenticeships.

"People learn in different ways. A trade school, where a school is doing hands-on-work, that's a way a lot of the kids learn," van Arkel says. "These kids, they need to know there are other options."

The morphing economy

The path to a job in Idaho wasn't traditionally through the classroom. It was in the field or the forest or mine. That reality has changed so gradually that many haven't noticed it. Blue collar and white collar have blended together. These days, auto body shops use computer programs to mix the paint they use to coat dinged fenders. The semi-trucks that cross Idaho's highways are equipped with high-tech computer systems.

"If you went into a sawmill 25 years ago, everything was done by hand," says Rod Gramer, president of Idaho Business for Education. "Now if you go into a sawmill, when they cut the boards, they do it by lasers and computers. It's all high-tech."

Technology has been a double whammy for underskilled Idaho: It's meant fewer well-paying blue-collar jobs that require a lot more training. Hess, at the Silver Lake Mall, knows what it's like looking for jobs without the degree on his résumé.

"It's definitely closed a lot of doors because I have all the experience in the world, but there's only so much you can do," says Hess. He has three Automotive Service Excellence certifications but needs 13 for full master certification. "I can't even get a job at a shop, and I've been working on cars since I was 8," Hess says. "If you're not master-certified, they just don't want you. "

Multiple studies have shown that in just a few years, 60 to 70 percent of Idaho jobs will require more than a high school diploma. Two years ago, Gov. Butch Otter's education task force unanimously set a goal to increase the number of 25-to-34-year-olds with postsecondary credentials from 40 percent to 60 percent by 2020.

"That's our North Star, if you will," Idaho State Board of Education Director Mike Rush says. Everything they do is geared toward improving that rate: "It is our economic future."

But when Bob Lokken, CEO of WhiteCloud Analytics in Boise, addressed the legislature earlier this year, he was blunt: It was already too late to meet the goal by that deadline.

And at least for tech companies, Lokken says, that's a huge problem. If you can't recruit enough talent locally, growth is slow and stunted. Companies look elsewhere, launching branches in other states, or even move entirely. Lokken saw it happen. In 2006 he sold the ProClarity Corporation to Microsoft, which he hoped would continue to hire engineers for its team in Boise. It didn't. "After four years of not being able to keep up with attrition, they shut it down," Lokken says.

That's the nightmare: If Idaho can't get kids to college, it won't hurt just their future, but the future of the entire state.

The struggling schools

When Education Week ranked Idaho a dismal 46th in the nation for education this year, it didn't just cite the state's bottom-rung postsecondary rate. It blamed the state's mediocre test scores, near-last per-pupil spending, and 50th-place ranking in early education — behind only Utah. It slammed Idaho for inequality: The reliance on local levies means Idaho schools in regions with higher property values raise money easier. So in Preston, schools get less than $5,000 per student, but in Blaine County, schools get more than $15,000 per student. Low pay means some districts struggle to recruit teachers who meet even the minimum qualifications.

Several of the kids interviewed by van Arkel said they could feel that the state didn't care enough to invest in education, that many of their teachers had given up on them and didn't care whether they were learning.

The state's high school graduation rate — 83.6 percent — is one of its few bright spots. But even that has some observers questioning whether the graduation rate is so high because standards are so low. Of the Idaho students who do make it to a four-year college, nearly a third never make it to their second year.

In fact, a letter from Idaho's education leaders last year, including then-Superintendent Tom Luna, blamed the state's lousy academic standards for not preparing "students for the rigors of postsecondary education" and contributing to Idaho's low college-going rate. (The solution, the tougher Common Core standards, isn't exactly beloved by North Idaho conservatives.)

Many Idaho kids are unprepared for the rigors of college. "A lot of those people have 4.0s and have to go to remedial classes when they go to college," Lokken says. Half of Idaho's community college enrollees have to take catch-up courses.

It's a massive task for Sherri Ybarra, the controversial new state superintendent of public instruction. When she proposed her educational budget to the legislature, she came under fire for her modest request — substantially less than the governor's — and lack of details. Despite repeated requests over the course of three weeks, Ybarra declined to be interviewed about the high numbers of Idaho students failing to enroll in college. "Right now she's worried about other stuff," spokesman Kelly Everitt says.

The State Board of Education, however, has been hammering away at the problem for years. It increased funding for the Idaho Opportunity Scholarship and made it available to more students. It pushed classes that also count for college credit — from 2008 to 2014, the number of high school students taking dual-credit classes grew from 5,000 to more than 12,000.

Two years ago, Idaho became one of only two states to pay for SATs for every student. The state held a "College Application Day," where students could apply to an in-state college without an application fee. College applications skyrocketed at the participating high schools.

Otter's latest proposed budget includes more money for teacher salaries, nearly $3.4 million extra for colleges, and an additional $2.5 million for college and career advisers in high schools. "I think Idaho education is on a good trajectory," says Rush, the state board of education director. "But we have a lot of work to do."

The local solutions

It's a rainy Friday morning at Sandpoint High School. Pennants from numerous colleges — Whitworth, BYU-Idaho, Carrington College, Montana Tech, University of Southern California — line the walls of the counseling center. Lewis-Clark State College enrollment specialist Justene Garner leads a small crowd of high school seniors through the nuances of dorm room setups, scholarships, parking passes, roommate matchups and the campus Quidditch club.

"Are you guys feeling way overwhelmed right now?" Garner says, her peppiness contrasting with the groggy unease of the students. "Like, overwhelmed to the max?

Garner's here to try to ease their minds.

Zale Filce, a Sandpoint senior with a red beanie and braided goatee, flips through a brochure. "How is it dealing with the paper mill?" he asks about the college's Lewiston location. "I hear it smells."

"That is the smell of the economy and money," Garner assures him. A lot of Filce's friends aren't planning on going to college.

"I have a friend currently who's dropped out. He's working at a pizza parlor," Filce says. "It's tricky, because they affect my life. I see what they're doing — that looks like fun."

But Filce is sticking to his plan: Go to college for business, nursing or physical therapy, get a solid job and then use that to support his passions: glassblowing and guitar manufacturing.

For the past seven years, Sandpoint High School has been a grand experiment. Supported by grants from groups like the local Panhandle Alliance for Education and the Albertson Foundation, the school has tried anything and everything to promote college.

Mire, the transition counselor, walks out of the counseling center, and there are a handful of students outside her door, thumbing through the "Great Wall of Scholarships" — multicolored folders taped against the wall and filled with scholarship paperwork.

"Look at these guys!" Mire says. "Taking their scholarships!"

She walks down the hall, where outside every teacher's room there's a poster with an educational story attached to it — where the teacher went to college, what they majored in, which activities they did while in school. Not just the teachers, but the counselors, the principal and the staff. Kids can see that the lunch lady went to the University of Wisconsin, majored in resource management and minored in biology.

Enter the library, where sophomores are tapping away at keyboards. "Adrenaline junkie job," writes Trevor Eidson, a kid with a Carhartt patch duct-taped to his cap. "Linemen have a job filled with danger and excitement at the same time."

The very first big paper that freshman students write is about what they want to do with their lives. The next year, they write about the education they need to get there.

So when Eidson graduates, he wants to be one of those guys who dares to climb power poles in storms to fix downed electrical lines. His friend beside him, in a camouflage jacket and mud-speckled black hat, wants to be a mechanic.

They both sketch out plans in their papers. Eidson's friend has his sights set on WyoTech — a Wyoming-based technical institute. Eidson calls up a Spokane Community College video about Avista's Pre-Apprentice Lineworker school. It's a pricey, exhausting four-month program, but at the end of it, if he's hired, a pre-apprentice groundman starts at $50,000 a year.

As for that intimidating financial aid paperwork? Sandpoint High countered with "FAFSA Frenzy" nights. Attendees scarf down pizza and sandwiches and enter raffles to win gift cards as they work through the knottier parts of pre-college paperwork. "First Generation" students — students whose parents never went to four-year colleges — have a club where they and their parents can work through each step of the college process.

All of this can seem a bit much to keep track of for a high school student. But there's an app for that, too. "They let you sign up for texting — they send you reminders," Filce says. "Here's scholarships coming out. Here's counselor meetings. Here's field trips." Filce says the school has taken him on multiple trips to see the North Idaho College campus.

At Sandpoint, applying for college is nearly mandatory. Senior Paige Schabell was dead set on not going; she wanted to travel instead. But Mire insisted that Schabell apply somewhere. She recounts sitting stubbornly in the library computer lab a few weeks ago as her classmates were applying for college, refusing to comply for most of the class period.

Finally, grudgingly, she applied to North Idaho College. "I applied so she wouldn't keep nagging," Schabell says. That, and a conversation with her mom, changed her mind. Now she plans to take Idaho community college online classes this summer.

So far, there have been encouraging signs. Sandpoint's SAT scores recently have been among the highest in the state. Student surveys the past few years have shown that about three-fourths of Sandpoint seniors plan to go to a four-year, two-year or technical college, with an additional 5 percent joining the military. Yet a year after graduating, only 59 percent of the class of 2013 had enrolled in college.

Sandpoint resident Jim Elsfelder, for one, doesn't have a college degree. He's 57 and has spent 40 of those years butchering hogs, cows and sheep in a meatpacking plant. He likes the variety, but he knows the cost as well. Coming home exhausted, clothes smelling like decomposing pig guts, with back, shoulders and neck aching. Or worse.

"I've had well over 300 stitches," he says. He lost a kidney after a bullet missed a cow's head, blew through his right side and tore through his liver, kidney and spine. He lost a tear duct when a roller fell on him, the hook swinging around hitting him in his eye.

Behind the scenes, Elsfelder and thousands of parents like him may be the most crucial players in changing Idaho's educational landscape: Parents who didn't go to college but are doing everything to make sure their kids get the chance.

His daughter, Sandpoint senior Topi Elsfelder, plans on attending the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology. "My parents always wanted us to be better than they were," she says. "They were always pushing us."

Her dad, like many in Idaho, still has a traditional job. But he looks around and sees firsthand how different the world is now.

"It used to be, a kid would get right out of high school and go to the mill or go cut trees. And that's gone away," Elsfelder says. "More [Sandpoint kids] are saying, 'I cannot get out of high school and make a living in this town.' Unless you want to flip burgers or cut hair." ♦