If you have hepatitis A, there's a good chance you don't know it.

You may feel tired or sick to your stomach. You may not feel hungry. Maybe your head hurts, or you feel achy, or you're itchy. But the first time you realize you might be really sick is when you look in the mirror and realize your skin and the whites of your eyes are yellow.

And by then, you've likely been contagious for a couple of weeks.

This is part of the challenge in trying to stop an outbreak of hepatitis A like Spokane has seen this year. Since April of 2019, there have been 70 cases of hepatitis A in Spokane County, according to the Spokane Regional Health District. Two people have died due to complications associated with hepatitis A in that time. It reflects an outbreak of the virus nationally, where there've been nearly 30,000 cases of hep A since 2016, and 298 deaths.

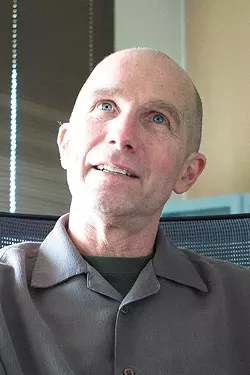

Many of those impacted by it are homeless, says Bob Lutz, Spokane Regional Health District officer.

"It's a problem that has disproportionately affected those living homeless," Lutz says.

Fortunately, thanks in part to the 124 vaccination clinics the SRHD has held since June, the spread of the disease locally seems to be slowing down. But for Lutz, the outbreak tells him that there's more work to do for the homeless population.

"If you don't have access to basic sanitary needs, then your risk is amplified," he says.

The encouraging thing about hepatitis A, a virus that infects the liver, is there's a vaccine for it that works extremely well. Two doses of the vaccine, which is recommended for children, are more than 95 percent effective in preventing hep A.

When the vaccine became available in 1996, the number of cases in the United States steadily declined — until 2012, that is. Then, for several years, outbreaks increased among adult populations due to imported foods, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But since 2016, the virus has been spread person to person. There's still a large population of unvaccinated adults who are vulnerable to infection. People who use drugs, experience unstable housing or homelessness, and men who have sex with other men are considered to have the highest risk of getting hep A.

That seems to correlate generally with the population that's been impacted in Spokane. A majority of the population that's been infected is older than 30, and 83 percent had a history of either being homeless and/or substance use, according to the health district. Only one person who was infected was vaccinated.

Hep A spreads from person to person through fecal matter, which can make it easy to transmit, says Malia Nogle, an epidemiologist with the Spokane Regional Health District.

"If you have it, and you don't wash your hands properly after using the bathroom, you can touch surfaces, people, food, cigarette butts, vapes, [you can] share utensils and that can cause it to be spread to other people," Nogle says.

The health district has held vaccination clinics in an effort to target populations that may be more at risk than others. That means at the jail, at shelters and warming centers, Nogle says. She says over 1,900 doses of the vaccine have been given.

Lutz says the outbreak could have been worse if it wasn't for the team effort at the health district collaborating with local partners. But he says the issue hasn't gotten as much attention as other kinds of outbreaks have. He suspects that has to do with the population most affected.

"This is not a topic that has really gotten much interest from the media," he says. "When you look at the homeless population nationwide, yes, it's become a politicized issue here locally, but it's a population we don't want to talk about."

Not having a home doesn't make someone inherently more likely to get hep A, he says. It just means that you may not have basic sanitary needs met — and that can make it more likely to be infected.

"Locally and societally, we do not provide those basic human needs to this marginalized population," Lutz says. ♦