The Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie aquifer is the only supply of drinking water for most of Spokane and Kootenai counties. It flows for about 370 square miles under North Idaho and Eastern Washington, starting between Spirit Lake and Lake Pend Oreille and eventually emptying into the Spokane and Little Spokane Rivers just west of downtown Spokane.

Yes, it flows — an aquifer is less like a subterranean bowl holding water and more like an uneven sandbox with a kid spilling a bucket of water at one end.

But before it can surface in the Spokane River, a lot of that groundwater is pumped up by municipalities, who then use it for flushing toilets, watering lawns, showering, irrigating crops and filling glasses from the tap.

Spokane County averages about 235 gallons of water use per person per day, which is among the highest water use in the nation. Runoff puts water back into the aquifer, but it's often contaminated with urban pollutants like fertilizers and microplastics.

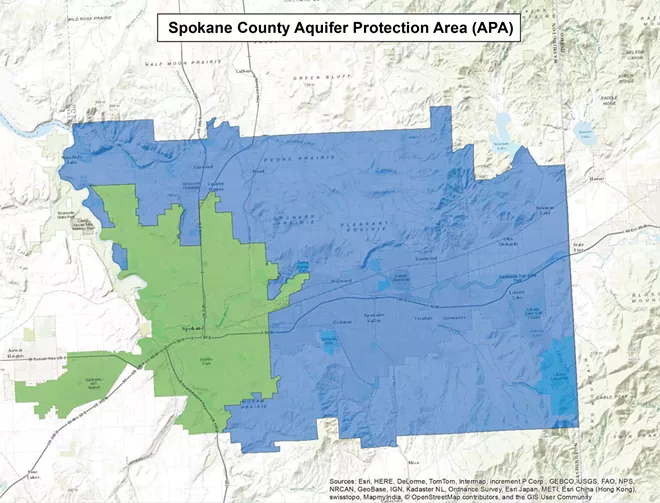

In 1985, voters in parts of Spokane County created an Aquifer Protection Area, a portion of the county where residents paid between $1.25 and $2.50 a month per household for 20 years to fund water quality monitoring and improvements (there were increased fees for commercial properties). The city of Spokane joined the protection area to focus on controlling nitrates in groundwater by creating a contained sewer system and removing more than 30,000 septic tanks and drain field systems, which allow treated wastewater to filter back into the ground.

The Aquifer Protection Area was renewed in 2004 for another 20 years, but that time the city of Spokane decided not to ask residents to participate in it again.

"[The sewer] work had been mostly achieved, and at the time, there weren't more complex testing or regulations around other pollutants we are now addressing like PFAS," Spokane Public Works spokeswoman Kirstin Davis says via email.

The Aquifer Protection Area currently covers some of the unincorporated parts of the county, plus Spokane Valley, Liberty Lake, Nine Mile Falls and Mead.

This fall, Spokane city residents may get a chance to decide if they want to rejoin. On March 17, Public Works Director Marlene Feist introduced the idea to the Spokane City Council at the Public Infrastructure, Environment and Sustainability Committee meeting.

The Aquifer Protection Area is up for renewal this election season, and if Spokane City Council members want to, they could introduce a resolution to add the city to the protection area when it goes on the ballot this fall.

"Obviously, protection of our sole source aquifer is really important to the city of Spokane," Feist said at the meeting. "We're the largest water provider in the region, providing up to 150 million gallons a day of water to our 230,000 residents, plus visitors and businesses."

Between 2000 and 2012, the city spent $220 million on water quality improvements through its Integrated Clean Water Plan. This included updating the Riverside Park Water Reclamation Facility, which treats 34 million gallons of wastewater every day and returns it to the river.

Rejoining the protection area would generate about $1.8 million yearly for the city, and Feist said Public Works would use the money for new projects to address pollutants, including "forever chemicals" like PFAS.

Both the city's Climate Resilience and Sustainability Board and the mayor favor the city joining the protection area, Feist said. But city officials need to take plenty of actions before the choice would be put to voters on the August primary ballot. City Council members would need to introduce and pass a resolution, and then the city would need to sign an interlocal agreement with Spokane County, which will be responsible for finalizing the proposal before voter education guides are sent out.

If voters renew it, the fee would be the same as it's been for the past 40 years, Feist says, and would cost each household unit $15 a year. The fee would be listed on property tax bills. For houses that have been split into multiple units, the $15 fee would be divided between residents as the landlord sees fit. Rates are different for large commercial or residential buildings.

Some residents pay an additional $15 per year if they use septic systems, rather than a municipal sewer system.

In addition to infrastructure, a portion of the revenue would go toward monitoring, which the county oversees. Since 1977, Spokane County has taken quarterly samples from 45 wells to check for nitrates, phosphorus, lead, arsenic, chloride and other pollutants.

"For 40 years, that's provided us with a lot of data, so we would intend to continue to support that," Feist said.

On the other side of the Washington-Idaho border, 66% of Kootenai County voters approved the creation of an Aquifer Protection District, which the Kootenai County Board of Commissioners then established in 2007. Kootenai is facing rapid growth — its current population is over 180,000 people, which is five times its population 50 years ago.

The protection district's purpose is the "protection of the state's economy, maintaining a water supply that does not require extensive treatment prior to human consumption or commercial use, avoiding the economic costs of remedial action, and protecting the well-being of communities that depend upon aquifers for essential human needs."

People who own land above the aquifer pay a $5.74 parcel fee each year. The protection district then helps fund efforts by the Panhandle Health District and Idaho Department of Environmental Quality. The dollars mostly fund inspections of businesses that handle hazardous chemicals.

Though the Idaho Legislature stripped public health districts of rulemaking abilities in 2021, local ordinances in 2024 reestablished Panhandle Health District's ability to enforce rules about the disposal of harsh chemicals above the aquifer. ♦

CORRECTION: This piece has been updated to reflect which ballot the Aquifer Protection Area renewal would be on. The proposal would be on the August primary ballot."