Judge James Lawless sat alone in his Franklin County chambers with a small, brown package before him. It was unusually heavy for its size, and inscribed across the top next to his name was the word "personal." Whoever sent the package intended for Lawless, and only Lawless, to open it.

A court clerk delivered the package to the judge's Pasco, Washington, chambers as he chatted with his fellow jurist, Judge Al Yencopal. Ordinarily a courthouse employee would have opened the small parcel, but the special instruction dictated otherwise.

As Yencopal left, Lawless tugged at the brown paper, then at the white paper underneath it. As he did, a blue pull cord yanked a pin from the pipe bomb inside. An explosion ripped through his chambers, launching dust and debris into the hallway. Yencopal came running, only to see Lawless slumped back in his chair, bleeding.

"Don't go in," he told the clerk, according to news accounts at the time. Lawless was pronounced dead later that afternoon.

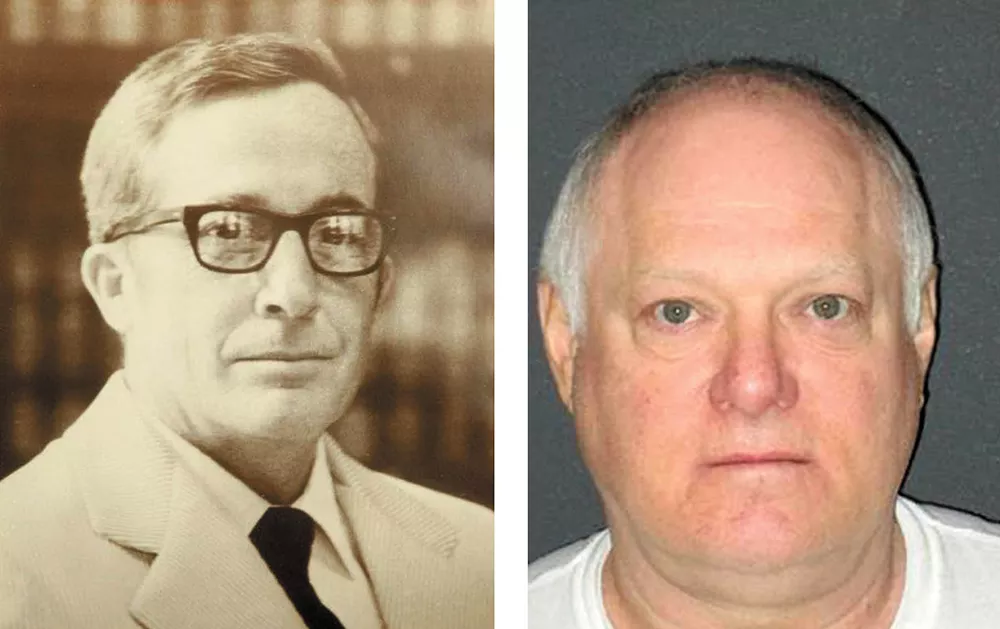

Ricky Anthony Young, the man convicted in 1975 for Lawless' death, was given a life sentence. He maintained his innocence until 1994, when he wrote an affidavit detailing his involvement in the plot to kill Lawless — admitting that he helped build part of the bomb, but had no role in the final assembly or mailing. In his letter, Young identifies some co-conspirators, but he is still the only person to be charged with the crime.

In November, attorneys with the Innocence Project Northwest, a legal clinic at the University of Washington dedicated to exonerating the wrongly convicted, asked that 24 pieces of evidence be preserved and tested by the Washington State Patrol Crime Lab. Those attorneys have since declined to comment when contacted by the Inlander, but the decades-old case is drawing attention in local legal circles, as some say the DNA could point to more suspects.

Franklin County Judge Bruce Spanner ruled earlier this month that the evidence will in fact be preserved. A hearing for whether or not it will be tested is set for Jan. 19.

"From our vantage point, the guy was convicted of first-degree murder by a jury trial," says Greg Lawless, the eldest of the five Lawless children. "It was a devastating day for the whole family that continues to this day."

James Lawless and Young had crossed paths before. The details of their previous encounters provided the prosecutor, Jim Rabideau, with a motive in both trials. The first ended in a hung jury.

In 1971, the then-19-year-old Young ran away with Margie Bishop, a Benton County deputy clerk's 15-year-old daughter. The two planned to flee to California and get married, experimenting with drugs and sex on their way out of town, according to court filings.

They didn't make it far. Young burglarized a Prosser, Washington, drugstore, looking for pills and cash, according to court documents filed by the Franklin County Prosecutor's Office this year. He escaped after police shot him in the leg, but later was arrested when authorities caught up with the teens in a remote "shack."

Young pled guilty to the burglary and faced 15 years in prison. Lawless showed him mercy, but not before he lectured the two runaway lovers.

"I will be completely candid with you," Lawless said to Young. "You have put the parents of this girl in an unfortunate position. They don't want to lose their daughter, and she's determined to maintain a relationship with you. Your background is such that you are about the worst possible example of a son-in-law that a parent could hope for."

He offered Young a deal: spend a year in the Yakima County Jail and five more on probation, rather than 15 years in prison, but refrain from any contact with Bishop.

"If you want that arrangement, speak up. If you do not, I'll send you to the Department of Institutions," Lawless said.

Young agreed. He served six of the 12 months, and then Lawless released him. He and Bishop were married on June 29, 1973.

It didn't take long for Young to find trouble. In the spring of 1974, several arsons and the explosion of a Benton County Sheriff deputy's car followed one of the biggest drug raids to that date in the area — 48 people were arrested, including Young. He was charged with "unlawful manufacture of marijuana," a felony. Authorities seized 72 plants.

At that time, Young's probation officer recommended that his suspended sentence be revoked in the burglary case for his suspected involvement in the arsons and explosion. A hearing was set in front of Lawless for June 6, 1974.

The package addressed to "Justice James J. Lawless" arrived June 3.

It took two trials to convict Young in the murder of Lawless. The first trial, held in Spokane, ended in a hung jury. The difference in the second was testimony from Young's cellmate, David McKinney.

"Strange enough, as so often happened in those days, they found a jailhouse snitch," says Sid Wurzburg, Young's defense attorney during his trials. "And that phony print they had was such a piece of junk."

The judge also denied Wurzburg's attempts to enter a piece of evidence. Letters from the "People's Army" were sent to local media at the time. They described in great detail the contents of the package and how the bomb was assembled, indicating that Young had some help. No one other than Young has ever been held responsible for the crime.

Rabideau, the prosecutor, says that Young's silence did him in with the jury.

"He had every chance to get up and testify," Rabideau tells the Inlander. "Ricky Young kept his mouth shut during the trial. That's what hung him."

When Young was convicted, fingerprint evidence was the "gold standard" of forensic science, attorneys for the Innocence Project Northwest wrote in their motion to preserve evidence. However, the limitations of fingerprint identification have been called into question. Take, for example, the case of Brandon Mayfield, an Oregon attorney the feds linked to terror attacks on four commuter trains in Madrid in 2004. Weeks later, the Spanish National Police said the prints belonged to an Algerian national.

DNA evidence now rivals fingerprinting as a powerful tool in court cases, though some experts caution that it's not perfect, especially when presented to jurors in a courtroom.

For example, the presence (or absence) of DNA does not prove innocence or guilt, though it certainly can help support the case. When a DNA profile is identified on a piece of evidence, for example, prosecutors will give the jury a number like one in 1 billion. That is the probability of finding a match among a random unrelated individual from an at-large population. That statistic can range from one in two to one in 1 trillion or more, depending on the quantity and quality of the DNA sample.

A mixture of two or more individuals' DNA complicates the evidence even more.

"That's where DNA science becomes a statistical interpretation," says Matthew Gamette, the director of the Idaho State Patrol's forensic services lab. "For mixed samples, we rely on statistical tools, and different labs might use different statistical analysis on that."

"If you get over three people, it's nearly impossible to deconvolute the contributors for that," adds Gary Shutler, the DNA technical leader for the Washington State Patrol Crime Lab.

For his part, Young submitted a similar request for DNA testing in 2001, but nothing came of it. Now, his attorneys argue that if the partial fingerprint used to convict him 40 years ago doesn't have his DNA, the state's biggest piece of evidence would be invalidated.

Franklin County Deputy Prosecutor Teresa Chen disagrees.

"The state has claimed from the beginning that Young conspired with others," Chen writes in a court motion opposing the DNA testing. "The presence of other DNA would only help finding other people, not exonerate [Young]."

In the rotunda of the Franklin County Courthouse, a plaque hangs outside courtroom three. In gold letters it reads: "Judge James J. Lawless Courtroom / Benton & Franklin Counties Superior Court Judge 1956 to 1975."

Lawless attended Gonzaga University Law School at night and worked during the day. He was elected as a Benton and Franklin County superior court judge in 1956 at 34, the youngest ever in the state at that time. He also served briefly as an interim judge on the Washington State Supreme Court.

"He was as sensitive a human being as I've ever seen on the bench," King County Superior Court Judge James Noe told reporters in 1974. "He is the last person you would expect this to happen to."

Greg Lawless was 20 when his father was killed. He says he didn't attend either of the trials back then, and has been paying attention to the recent developments, but it's difficult. Thinking about the case dredges up devastating memories, he says. But he also remembers his father's wicked sense of humor and gentle nature.

Occasionally, Lawless, now a real estate attorney in Seattle, would accompany his father to that city for work. He recalls checking out of the luxurious hotel the county had booked, opting for a cheaper one down the road.

"That's the kind of man he was," Lawless says. "He was a good person, and the most honest human being." ♦