What Came True

The year is 1986 and it’s race day. More than 48,000 have registered for the official Bloomsday race, and for the first time ever, there are more women participating than men. More than 5,000 volunteers assist the nearly 45,500 who finish the race. While all this is going on, Don Kardong, founder of Bloomsday, asks those involved with the race to look ahead: What will Bloomsday be like in the year 2001?

While the prediction about the enclosed skywalk system from downtown to NorthTown has yet to achieve reality, the following are some of the predictions from those 1986 interviews that did come true — even if not quite on time.

• “Runners will use their home computers via the telephone system to register for the run, and their entry fees will automatically be deducted from their checking accounts,” said Tom Cameron, who ran the check-in at the convention center. This, of course, is exactly how things work now, although we’ve moved past the dial-up connection. The other part of Cameron’s prediction was a huge miss, though. He expected 275,000 runners by the 2001 race. Let us be grateful he was wrong.

• “By the year 2001, we should have the technology to read everyone’s start and finish times electronically, probably with some kind of transmitter on the runner number. Finish times would be automatically and instantaneously available at the end of the race,” said George Schwartz, who worked on the timing system in 1986. Schwartz’s idea was seen as out-there at the time. A similar idea, suggesting a card-scanning checkpoint system, was hailed as “far-fetched.” But in 2004, race organizers introduced electronic chips that runners wear around their ankles to track times with extreme accuracy. Kardong says the introduction of these chips catapulted Bloomsday’s popularity.

• “In the future, I hope the celebration part of Bloomsday will expand beyond the runners. I’d like to see those thousands of people watching all along the course join in, doing their own thing, having little side-shows or whatever along the way, so it becomes one long street fair, with everyone involved,” said Dan Leahy, a Bloomsday photographer. While there have been certain entertainers along the route since the beginning of the race, it was only 10 years ago that Bloomsday planners started booking performers for the race. Along with the addition of the performers, Bloomsday has become a huge spectator event, drawing thousands of non-runners to gather along the course. (TIFFANY HARMS)

A Look Back at Bloomsday ’77

A man driving his car had mapped out an 8-mile course through the city, beginning at the Opera House and ending back at the Washington-Stevens couplet. For $3, runners registered for the race, which began at 1:30 pm. It was 81 degrees outside, and Don Kardong remembers the problems the heat caused for runners.

“The very first year was the first time I’d ever seen heat stroke. ... I just remember looking around and seeing these people who looked like they were having seizures, which I guess is what heat stroke can look like. We were just not prepared for that,” said Kardong.

That first race day was the hottest to date, matched only by 1980’s contest, which also saw a high of 81 degrees. The coolest years were 1984, which had two inches of snow on the morning of race day, and 1999. Both had highs of 47 degrees. (TH)

Getting to the Race

Come race day, downtown Spokane and surrounding areas become flooded with the massive surge of runners and families. It can make getting around tough, especially if you’re driving. Rather than hunt for that elusive parking spot in the thick of the action, it’s best to ditch the car on the outskirts of the festivities and either hike or opt for one of the following:

Bloomsday Bike Corral: For the past 18 years, the Spokane Bike Club has been keeping an eye on Bloomies’ bikes in their Bloomsday Bike Corral. The corral is open to all race participants from 7:30 am-2 pm in the Central Meadow of Riverfront Park, south of the former YMCA building and adjacent to Howard Street. The club says Bloomies are also welcome to leave their extra belongings with their bikes, which makes this the perfect option for those either traveling to the race alone or just looking for the quickest getaway afterward.

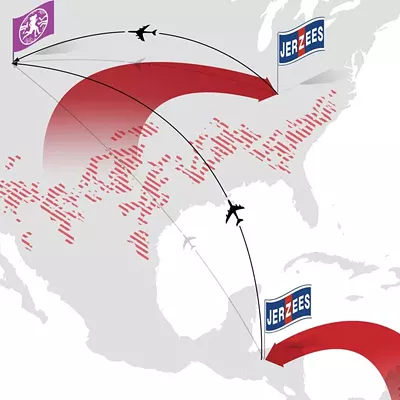

STA: Spokane Transit runs shuttles from four locations — the Spokane Valley Mall, Ferris High School, NorthTown Mall, and Eastern Washington University — and will drop riders off right on First Avenue between Post and Stevens streets. Buses depart for the race between 6:30 and 8:30 am and head back to their original locations between 10:30 am and 2 pm. Cost is $1.50 each way for riders over age 7 (exact change required), unless you have a pass, but you must buy your pass ahead of time at the Bloomsday Trade Show’s STA booth during Bloomsday check-in on April 29-30. You may also purchase your pass online when you register, but you must pick it up at check-in as well. Note that STA monthly passes do not apply on race day. Visit spokanetransit.com/bloomsday.asp. (TH)

Bloomsday Trivia

• After the 1994 reconstruction of the T.J. Meenach Bridge, the Bloomsday course had to be recertified and was inadvertently mismeasured. In 1994 and 1995, because the course was about 70 yards short, some 11 seconds had to be added to most of the elite runners’ times.

• In 1979, pounding feet caused the Maple Street Bridge lampposts to sway.

• During the course of Bloomsday, depending on your stride length, each of your shoes will hit the pavement between 6,000 and 8,000 times.

•In 1996, the oldest Bloomsday finisher was Cecelia Kelly, age 105.

• In addition to organizing the race, Don Kardong runs Bloomsday every year. A long-time runner, he placed fourth in the 1976 Olympic Marathon and won both the 1978 Honolulu Marathon and the 50-mile Grizz Ultramarathon in 1987. Despite being on his game, he couldn’t stay focused that first year. “In the first year, my head was definitely not in the race. I was just saying, ‘Oh, that water aid station was not operated properly, and this was wrong, and where was the timer,’” says Kardong. “But things go so smoothly now, I can just think about my own performance.”

• Kardong originally had a runners-only event in mind for Bloomsday. Walkers were allowed in the second year after a couple of board members realized the potential for greater community involvement. Kardong says this move was largely responsible for Bloomsday’s ultimate success. (TH)

The Elite Field

This year, as in most recent years, Kenyans will likely chase Kenyans for the Bloomsday crown.

A Kenyan man, after all, has won Bloomsday for 16 of the last 18 years. Last year, the top eight finishers were Kenyan. The women’s draw is slightly more diverse. Kenyans have won only 10 of the last 16 in that contest. But last year’s champions both hailed from the east African nation.

This year, defending women’s champ Lineth Chepkurui will try for a record fourth win in a row. Last year, Chepkurui set an unofficial world record for 12k races in Spokane. She broke her own record two weeks later at San Francisco’s Bay to Breakers.

Jon Neill, Bloomsday’s elite athlete coordinator, thinks the field won’t be as tough for her as it was last year, but “she’ll have her hands full with Jelliah Tingea” (a Kenyan who won the Cherry Blossom 10-mile race in Washington, D.C., on April 3) and Shewarge Amare, from Kenya’s northeastern neighbor, Ethiopia. Amare is coming off a very competitive 10k win in Charleston, S.C. Neill also says to look out for Kenyan Risper Gesabwa. “She will definitely be in the mix.”

Men’s champion Peter Kirui was scheduled to run, but won’t make it this year because of visa problems, Neill says. Nevertheless, there will be some notable Kenyan competitors. Among them, Julius Kogo just won the Pikes Peak 10k “in very swift fashion.” Allan Kiprono and Lani Kiplagat took second and fourth, respectively, at Washington, D.C.’s Cherry Blossom.

For most of us, Bloomsday is a fun little road race. For a large chunk of the elite field — and especially those from East Africa — it is incredibly serious business.

The median household income in Kenya is a little more than $1,000 per year. Half of the population lives on less than $400. The winner of Bloomsday this year will take home $7,000, enough to support a family for a very long time. (LUKE BAUMGARTEN)

Ups and Downs

Only 1,198 runners finished Bloomsday 1977. Not bad for a first-time event, but compared to later years, ’77 was scarcely attended. The next year, the number of finishers more than quadrupled, to 5,024, and the year after that boasted just over 10,000. The steady increase in numbers more or less continued until 1996, when 56,156 finishers were counted. But just as steadily as attendance had grown, it began to dwindle the following year, the first in a seven-year dip.

“We don’t really know why it goes up and why it goes down,” says Bloomsday organizer Don Kardong. He adds that larger societal trends have an impact on Bloomsday attendance, but he also notes three factors that he believes have been responsible for the steady rise in attendance since the dip in the early 2000s:

• The introduction of computer chip timing in 2004 made Bloomsday more desirable to runners due to the appeal of the system’s accuracy. The chip also eliminated the need for a staggered start time. Kardong said that prior to the chip, some runners had to wait as long as a half-hour to start the race.

• Running events have grown nationwide, and it’s no different in Spokane.

• In the sour economy, people are looking for events that are close to home rather than ones they have to travel far away for — “the old ‘staycation’ idea,” says Kardong. (TH)