As a young person in Ethiopia, Kassahun Kebede and his family were displaced from their homes more than once, in something the Ethiopian government called resettlement. Those experiences later propelled him into his now nearly two-decade career researching population relocation, international migration and the new African diaspora — the voluntary movement of Africans to the U.S. and other countries in the latter half of the 20th century.

"Growing up, I just became a displaced person in my own community," he says. "Mobility has always fascinated me."

Recently, his research has delved into the identity development of second-generation Ethiopian Americans and how the Ethiopian diaspora (dispersed from their homeland) advocates for democracy across international borders.

As someone who now identifies as Ethiopian American and has children who would be considered second-generation Ethiopian Americans, Kebede says his own biculturality is what really drove him to research the formation of transnational identity.

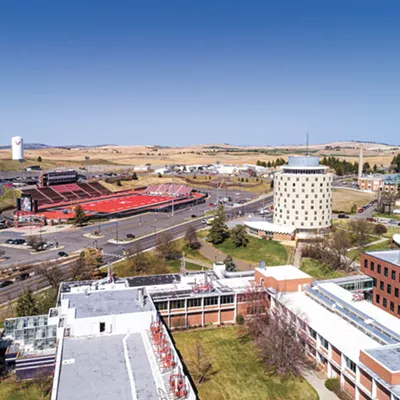

The associate professor of sociology and justice studies at Eastern Washington University says there are a few facets of his research into the Ethiopian American transnational identity.

Kebede studies the challenges that people face, how they are adapting and how they contribute to the culture in the U.S. To track this he looks at a handful of metrics, such as the percentage of immigrants who own their own business (about 20%, according to Kebede) or more noticeable day-to-day changes, like the items that can be found in the supermarket.

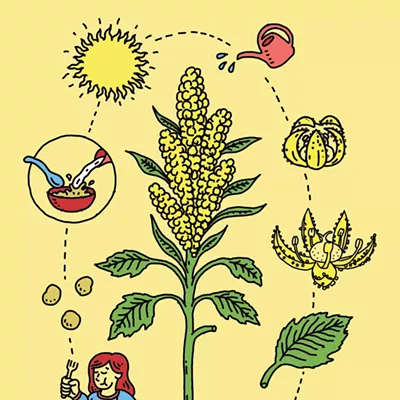

"I was surprised the first time I went to the store and I found teff (an ancient Ethiopian grain), and I never thought I would find any Ethiopian food," he says. "These ingredients didn't exist here 20 to 30 years ago."

His research into democracy across borders has taken a more hands-on approach with the recent creation of the Libraries for Ethiopia Fund. In his capacity as the nonprofit's president and director, Kebede is raising funds for his home country, which has fewer than 250 public libraries serving more than 120 million people.

"Democracy is not about going out and preaching about who you are or who you would vote for," Kebede says. "It's about giving back to the community you come from, almost like a gift for your absence."

Unlike other studies that require more specific scientific methods, Kebede's research relies on an interpersonal approach. This often includes multiple interviews with his subjects and a technique known as immersion, which he describes as a deeper kind of "hanging out." For this, he spends time each summer in the Washington, D.C., metro area — which has a large Ethiopian population — and observes what's happening in that community.

He also plans to conduct his research locally, working with Spokane Public Library and Thrive International. Those two organizations are partnering to build housing for refugees, and Kebede wants to interview the people who end up living in those apartments.

"There are always people who may struggle," Kebede says. "But overall, [second-generation immigrants] are thriving in this environment because the U.S. is more welcoming than it used to be."

In 2013, the U.S. Census reported that second-generation immigrants are much better off, in socioeconomic terms, than their parents. This includes higher household income, higher college graduation rates and a larger share who are homeowners.

But Kebede's research doesn't compare second-generation Ethiopian Americans with their parents — he compares them with everyone else in their same age group. And what he's found so far indicates that they're often outpacing their peers in those same metrics, too.

Looking at the larger picture, there are more immigrants in the U.S. than in any other country in the world, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. It's often been described as a melting pot of other cultures into one American society.

But if you ask Kebede, the U.S. would better be described as a place where multiple tapestries can be formed by the weaving together of different cultures.

"It's an American culture to weave things together," he says.

His research is affirming that thought, finding that the U.S. continues to be a place in which immigrants thrive and create space to mix their identities into a new transnational identity. Even though this country is filled with structural barriers for marginalized groups (like immigrants), Kebede says more often than not, people are going to find a way around those barriers.

"People think that structural factors limit their ability to move up when they're an immigrant," Kebede says. "But people will always try to find a way around it.

"That's essentially the nature of America," he adds, sporting a huge smile.♦