Indigenous women across America face disproportionate levels of violence.

It's an epidemic — an often-underreported crisis centuries in the making — with a complex web of causes. Much of it comes down to jurisdictional issues, lack of data, generational trauma and an ambivalence on the part of authorities.

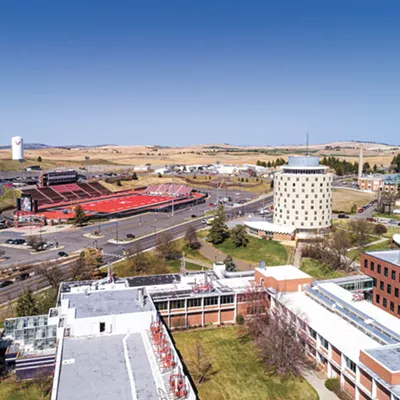

The crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women is something that Margo Hill, a member of the Spokane Tribe and an urban planning professor at Eastern Washington University, has spent years tirelessly advocating for more awareness of. She's become a national expert on the topic — publishing research, improving data, training officials and pushing the state to fund a tribal liaison dedicated to the issue in Eastern Washington.

"All the work I do, it has to be work that matters," Hill says. "I don't do any research for the purpose of theory — I have to do work that helps my community."

Hill began her advocacy and research work about five years ago, while working on a project to reduce traffic fatalities on reservation roads with a grant from the state Traffic Safety Commission. She soon saw that the way people travel on reservations was directly connected to the stories she'd heard of human trafficking and violence against Indigenous people.

The reservations that Indigenous people were forcibly relocated to are usually in rural areas, with long distances between jobs, health care and education. These vast open spaces are difficult for understaffed tribal police to patrol, and many young Indigenous women don't have cars, forcing them to rely on unreliable public transportation or hitchhiking.

On those roads, at isolated truck stops and bus stations, people are often most at risk, Hill says.

Hill has worked with graduate students to map those connections, showing how the geography of reservations and their relationship to major cities like Spokane can make Indigenous people vulnerable to trafficking and violence.

She's also worked with agencies like the Washington State Patrol and Washington Department of Transportation to train employees and raise awareness about the danger.

Highway rest stops are often hot spots, so Hill will meet with maintenance workers to help educate them on what to look out for. Like a scared-looking young woman getting into a car, or a parked motorhome with men waiting to get in and out.

"Basically, if you see something, say something," Hill says.

You don't need to confront the trafficker yourself, Hill says. She recommends an app called "Truckers Against Traffickers" that anyone (not just truckers) can download to report suspicious activity.

Before coming to Eastern, Hill spent a decade working as an attorney for the Spokane Tribe. It was there that she saw how a tangled web of jurisdictions can create gaps and make it difficult to bring perpetrators to justice.

Tribal courts and police departments are limited by a Supreme Court ruling which held that tribal courts can't prosecute non-Indigenous people for major crimes.

"So all these cases of murdered and missing Indigenous women, if they involve domestic violence or rape or homicide, tribes have their hands tied behind their back with no ability to go after these perpetrators," Hill says.

As an attorney, Hill says she regularly received letters from the U.S. Attorney's Office declining to prosecute cases — even for cases involving violence or molestation that had ample evidence.

Things have slowly changed.

"Today, they're stepping up and paying attention to those cases that are happening in Indian Country, because they get raked across the coals in Senate hearings in Washington, D.C.," Hill says.

Efforts to address the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women have long been hampered by problems with data, Hill says. Various agencies have different methods for reporting, and basic information — like contact info, race and when the person was last seen — are often lost.

"All the work I do, it has to be work that matters. I don't do any research for the purpose of theory — I have to do work that helps my community."

Hill says data collection has also improved significantly in Washington state. She recently worked with a graduate student to map data on missing Indigenous people by county, and the Washington State Patrol now publishes regular maps with the names of missing Indigenous people and contact information for the various agencies.

In early May, 142 Indigenous people were missing in Washington state. Ten people were missing in Spokane County.

Hill has also worked with leaders from the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians to secure funding for an Eastern Washington Tribal Liaison position with Washington State Patrol. The liaison works directly with families, sharing information, answering questions and helping coordinate across multiple law enforcement agencies.

Public and institutional awareness of the crisis has improved dramatically in recent years, Hill says. Politicians at the state and local level are talking about the issue and taking it seriously, and local law enforcement are increasingly engaged and looking to collaborate.

"When I do training for law enforcement, I can look them in the eye and say, 'Thank you for working with our families,'" Hill says.

But there's still a lot of work to do. Communication across jurisdictions needs to improve. Tribal law enforcement needs more resources. Tribal courts need greater authority. Drug and alcohol treatment needs to be expanded.

For her part, Hill plans to keep fighting.

"We're not going to be silenced anymore," Hill says. ♦