The end of a Bloomsday run is glorious. There’s nothing quite like that slow, victorious meander across the sun-drenched Monroe Street Bridge.

Then you get to the T-shirt turnstiles. The race is officially over — you are a finisher.

But not many finishers know that getting that shirt takes more than 12 kilometers. It involves global geopolitics, the occasional natural disaster and the whims of Wall Street speculators. It’s quite a hassle.

“This has been the hardest year, for sure,” says Don Kardong, Bloomsday’s founder and continuing head honcho. “It’s quite amazing,” he says about the complexity of procuring 50,000 shirts at once.

Since Bloomsday began in 1978, Kardong says he’s purchased almost 1.4 million T-shirts. That comes to about 700,000 pounds of cotton, or about two cotton plants per T-shirt.

And that’s where it all begins, in a field of cotton. Cotton picking goes back 8,000 years and is grown on every continent but Antarctica. It’s a global affair, but the Bloomsday cotton begins somewhere in North or South America.

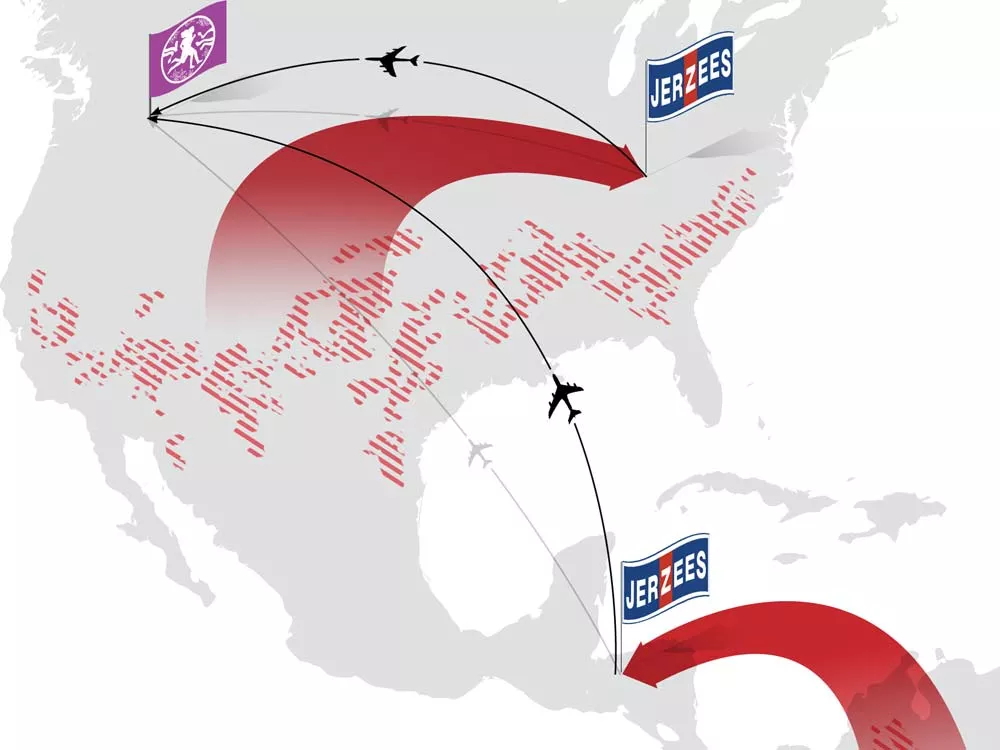

“We don’t source any of our cotton from Asia,” says Todd Gilmer, a national account executive for the northwest division of the Russell Corporation, a subsidiary of Fruit of the Loom that owns the Jerzees brand, this year’s manufacturer of Bloomsday T-shirts. “We’re a completely vertical manufacturer. We spin the yarn. We knit, cut and sew it. That’s a pretty simplistic explanation, but that’s the nuts and bolts of it.”

After the cotton is harvested and ginned — the process that separates the valuable fiber from the seeds — it is shipped in its “raw” form to Russell’s factories in either Leesburg, Ky., or Merendon, Honduras.

From there, T-shirts, underwear, sheets — you name it — emerge.

Recently, 50,000 blank shirts (the color of Kardong’s choosing) came to Spokane. A local company, Wildrose Graphics, is putting the design on it.

“If we want to get a unique color, that can be a challenge,” Kardong says. “In the past, when there was plenty of supply, we could get any color. This year, their supply was down, and it was really difficult to find a color we wanted in all the sizes we need.”

Kardong wouldn’t say what color was chosen — it’s a surprise for race day. “I think we had to tend to a more a common color,” he says.

The last few years have been rough for cotton, as for all commodities.

First, the economy took its toll.

After years of steady yields, American cotton precipitously dropped. In 2005, American farmers produced 11.5 billion pounds of cotton. By 2009, less than 6 billion pounds of cotton were cultivated. Things weren’t much better elsewhere.

Floods in India and Pakistan — two of the world’s largest cotton-producing and -milling nations — destroyed crops. India lost about 15 percent of its crops in the Punjab region, its cotton belt, and yarn prices went up by 60 percent in Pakistan.

“Cotton farmers in China are hoarding the cotton because of the price,” Russell’s Gilmer says. “They’re storing cotton in barns while the price goes up.”

But the price jump didn’t stop with hoarders. “Cotton’s a commodity,” Gilmer says. “Wall Street’s got involved. The futures market is affecting the price as well. Speculation.”

But the shirts have arrived in Spokane, so Kardong doesn’t have to worry about it. That is, until next year.