Mama can’t find a steady job. So Zettie goes to bed every night in a cold, cramped car and wakes up every morning to the peal of police sirens.

Daddy forged a check, got caught, and thrown in jail. So Amber and Essie curl up against one another when peanut butter and jelly doesn’t fill their tummies.

“There’s no room for ‘want’ around here,” says Grandma, “just ‘need.’ ” So Jeremy buys a pair of thrifted name-brand shoes he covets, but they’re a size too small. In the end, he gives them to a friend who needs them more than he does.

A few years ago, Janine Darragh, then a Ph.D. student at Washington State University, read and reread dozens of picture books about children grappling with poverty. Consumed by their tales, she often dreamed of these characters; one night they descended upon her house, begging for a Thanksgiving meal.

Against the backdrop of one of the country’s worst economic crises, Darragh wondered: How accurately do contemporary children’s books reflect the reality of American poverty? And what messages do they send kids about financial hardship?

Darragh, now an assistant professor in education at Whitworth University and self-professed “book nerd,” says books should honestly reflect students’ socioeconomic realities. About 16 million American children, roughly one in five, live in poverty — a decade high. In Spokane Public Schools, 57 percent of families are eligible for free or reduced lunch.

“Books like Great Expectations or The Scarlet Letter don’t necessarily connect to students,” she says. “If a student is struggling with something and sees a character in the book whose parent might have lost a job or has to live in a shelter for a while, then that can be connected to his or her self-worth and self-esteem, to feel like he or she is not alone.”

For her Ph.D. dissertation, she and Jane Kelley from Washington State University analyzed 58 picture books published after 1990 portraying American children living in poverty, and compared their results with Census Bureau data.

Their findings, which were published in 2011, were somewhat surprising: While demographic trends in gender and race are more or less on par with Census statistics, “there was a huge discrepancy,” as the authors write, in geographic setting. Although 44 percent of impoverished people live in rural areas, of the children’s books they studied, only 17 percent show present-day families struggling to make ends meet in the countryside.

“I was surprised. I didn’t think there would be very many depictions of contemporary rural poverty, but I didn’t think it would be as glaring as it was. It was really challenging to find books at all,” she says. “It also was a little bit disappointing to see how issues of poverty were oversimplified.”

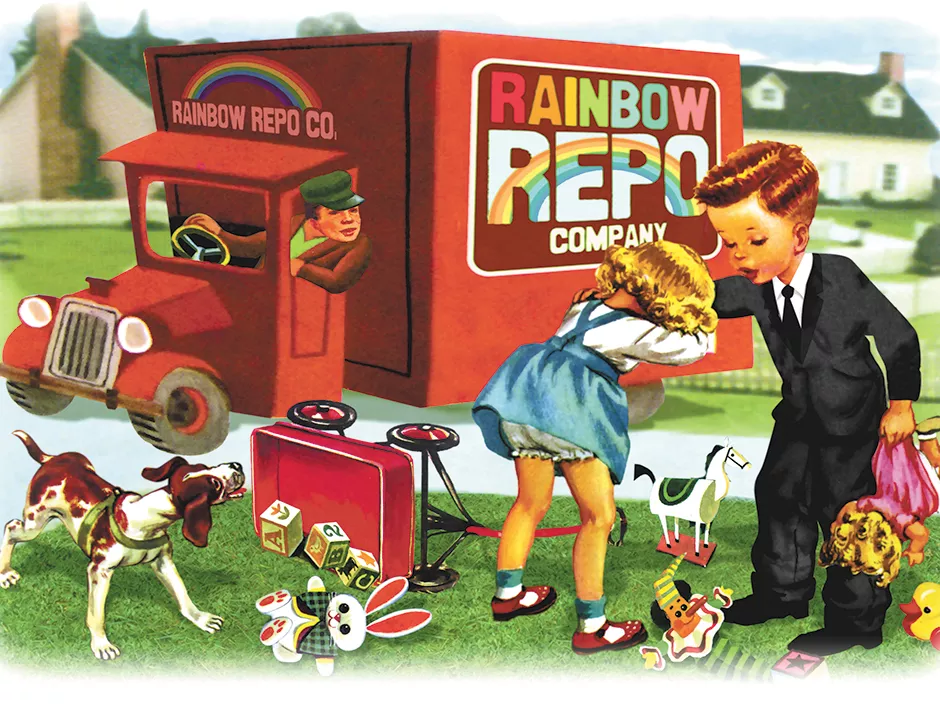

Corroborating earlier studies, they found that structural roots of poverty are often ignored. Characters pick themselves up by the bootstraps; they rely on luck and resourcefulness. They find a four-leaf clover or make a wish on birthday cake, and — surprise — good fortune and material possession abound. Poor families, Darragh says, are too often “romanticized.”

Despite these disappointments, she uncovered quite a few gems in her research. Darragh gushes about her favorite books: A Shelter in Our Car by Monica Gunning tells a tender tale about a girl and her mother, Jamaican immigrants, who must scavenge for food and bathe in a public restroom because they can’t afford an apartment. Amber was Brave, Essie was Smart by Vera B. Williams is a bittersweet portrait, written in verse, of two sisters who protect each other through good times and bad. Those Shoes — “a really sweet book” by Maribeth Boelts — chronicles a little boy who dreams about owning a pair of black high-tops, but Grandma only has the money for new winter boots.

“I think they were honest portrayals,” Darragh says. “Kids struggle, but they’re kids. They still like to play; they still have hopes and dreams, so they were not overdramatic, definitely not didactic or preachy. [They] just told a story where the child happens to be struggling economically, and with a good interesting story, which I think is most important.”

Darragh says she first noticed these gaps in children’s literature almost 20 years ago when she started her teaching career at a rural high school in southeast Ohio.

“I was having a hard time finding depictions of rural poverty for children to read, for other students to know rural poverty even exists,” she says. “A lot of the times when you turn on the news and see depictions of poverty, it’s more the inner city,” she says. “If you’re riding on a bus 45 minutes to get to school, people might not even know the struggles that you’re having.”

Darragh is currently replicating the study with Craig Hill from Washington State University, but this time, she’s looking at young adult novels. She urges her students — all future teachers — to ask critical questions of the books they’re choosing for their classes.

“Who’s telling the story? What story is being told?” she says. “Teachers [should] be super-careful in the books that they use and how they use them to make sure that they’re not unintentionally sending messages to students about stereotypes of people in poverty.”