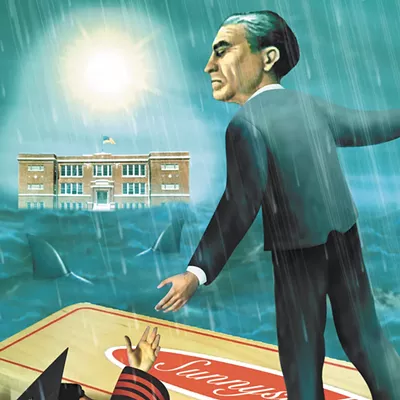

In a January Science magazine story about his work, the word "heretic" is splashed in teal letters across the page. On those pages and elsewhere, he's been called a "maverick" and a "pioneer," winning over some of his fellow scientists while outraging others.

That's because Washington State University's Michael Skinner has called into question the fundamental scientific understanding of what makes us susceptible to disease. Until now, he says, much of science has been built on the understanding of genetics as the way we inherit traits and on the belief that mutations in our genetic material — our DNA — are what make us susceptible to diseases like obesity and cancer.

"What I'm suggesting is that the DNA sequence is very critical — we can't live without it — but it's only a small piece of a much bigger story," he tells the Inlander.

The rest of that story, according to Skinner, can be seen in the work of his lab. There, he and his team are exploring another way inheritance happens, and they're finding links between toxicants like pesticides and jet fuel and conditions like obesity, even generations after the toxicants are introduced.

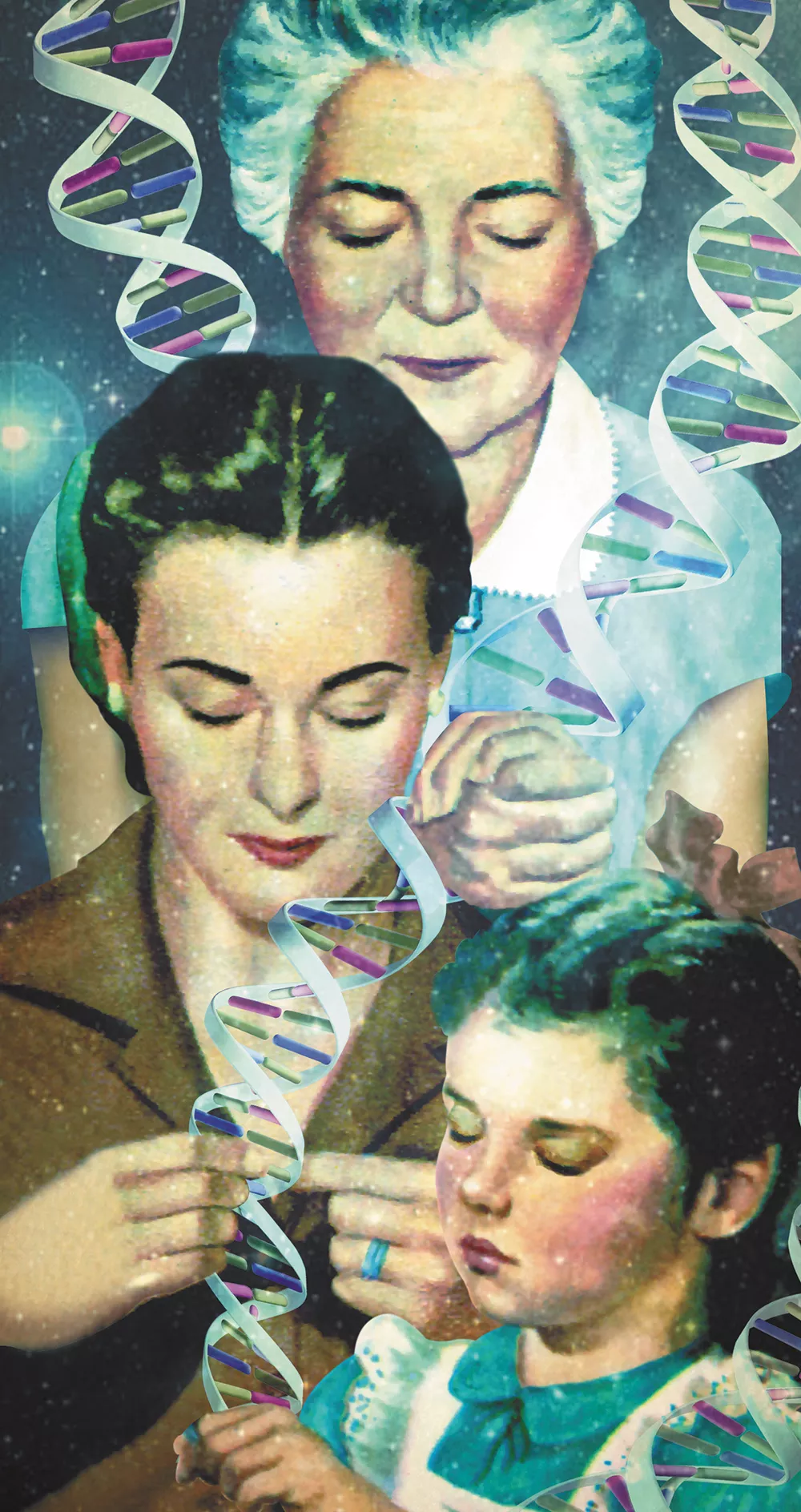

"One way to explain this is that what your great-grandmother was exposed to when she was pregnant can influence your ability to get a disease that you're going to pass on to your grandkids, even though the only one exposed was your great-grandmother," Skinner says.

When Skinner's lab injected pregnant female rats with toxicants while their fetuses were developing, they found that the exposure affected not those rats or their offspring, but their offspring's offspring. And rather than genetic mutations, they saw changes in the epigenetics — the chemical modifications to DNA and proteins around the DNA that determine which genes are on and off, helping to influence things like, for example, whether a developing cell will become a brain or heart cell. The change to that epigenetic process altered the rats' susceptibility to disease, making them more likely to get sick, and remained apparent in subsequent generations.

Since its initial findings 15 years ago, the Skinner Laboratory has studied the effects of eight toxicants and found that while the results varied some, all resulted in an increased tendency toward disease across multiple generations.

Not only is Skinner challenging a biological bedrock, the toxicants he's using and the resulting diseases are getting people's attention. The lab has exposed rats to jet fuel, the pesticide DDT and the chemical Bisphenol A (or BPA), recently banned from plastic baby bottles and sippy cups. The conditions to which the rats became more susceptible included obesity; brain abnormalities; and kidney, testes, prostate, ovarian and mammary diseases. The most recent findings around DDT come as the World Health Organization continues to encourage the use of the pesticide to fight malaria in developing countries.

It's not the first work to suggest that more than just genetics may be affecting our health. Studies of families who've lived through famines have shown more negative health effects among the children and grandchildren of women who were pregnant during the famine. Skinner says that along with when we're fetuses in the womb, our most sensitive exposure periods (the times when environmental factors can change our epigenetics) are during the first five years of life and during puberty.

"It's not just pollutants," Skinner says. "Your nutrition is your biggest exposure: the foods you eat, the waters you drink and bathe in."

While Skinner does point out the potential ramifications for humans, it's important to note that his lab is not doing "risk assessments." Researchers there are not necessarily exposing rats to the same amounts of toxicants that humans would encounter. They're not measuring how much DDT it takes to cause an increased likelihood for obesity. Instead, they've been working to understand whether these outside factors can influence rats' susceptibility to disease, and how. That, Skinner says, eventually could lead to more understanding of the phenomena in humans, even the possibility of mapping our personalized exposures and what diseases we may be most susceptible to, in order to focus on preventing them before they take hold.

As Skinner continues his work, he is likely to continue facing skepticism from those who believe genetics alone provide the answer. But he sees the research as part of a "paradigm shift." That he's challenging the status quo and attracting labels like "heretic," he says, just "means I'm doing something important." ♦