Cedric Habiyaremye learned what it's like to be hungry when he was 7 years old.

It was spring 1994, at the start of what would become known as the Rwandan genocide. Habiyaremye and his family were forced to flee their home in Gafunzo, Rwanda, and faced severe food insecurity as they made their way to a refugee camp in Tanzania.

"I faced hunger and starvation for the very first time," Habiyaremye says. "The only thing that kept us alive was beans."

Even after arriving at the refugee camp food remained scarce. When Habiyaremye and his family were finally able to return to Rwanda three years later, he saw how the chaos and violence had left the country with a dire shortage of food.

"That's when I thought that, if I survive, I want to study agriculture and see ways we can never go to bed hungry," Habiyaremye says.

He attended the University of Rwanda College of Agriculture and connected with a program called Building Bridges with Rwanda, which allowed him to pursue a master's degree at Washington State University's College of Agricultural, Human and Natural Resource Sciences in 2013. He stayed at the college and obtained a Ph.D. in agronomy and crop science.

That's where he discovered quinoa.

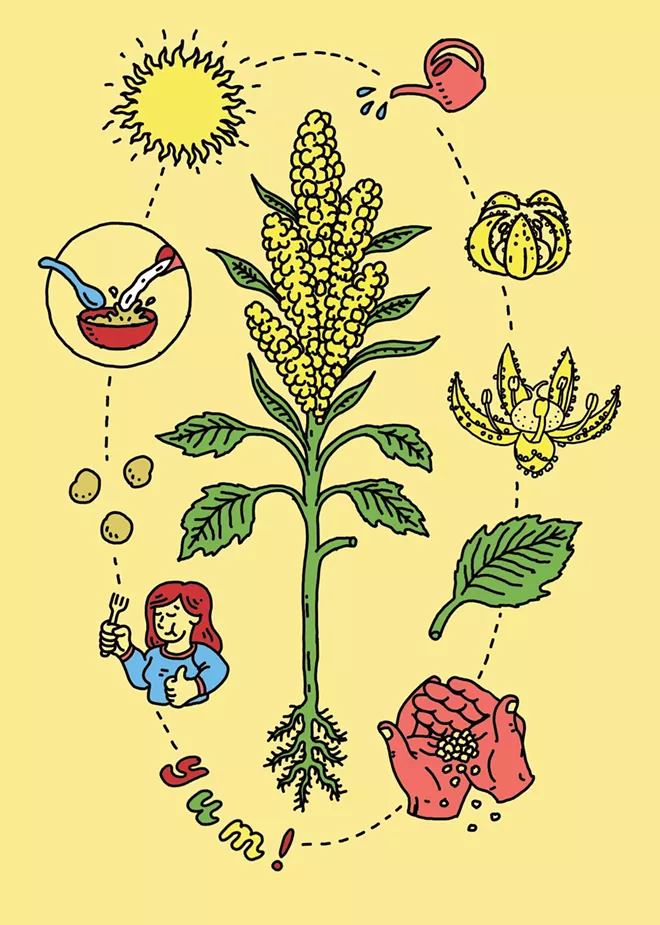

The crop is rich in nutrients and highly resilient. It can thrive in poor soil conditions, can be stored for long periods of time and has leaves that can be eaten while it's growing. People can use it to make drinks, flour, food for animals and a host of tasty dishes.

Habiyaremye realized that quinoa could be the solution to Rwanda's hunger crisis he had been looking for.

In 2015, Habiyaremye took a small amount of seeds to Rwanda and introduced quinoa to local farmers. Some were skeptical at first — quinoa was totally new to the region.

"It was a new crop — nobody knew about it — so it was hard to get partners in the country," Habiyaremye says. "Some were hesitant to start."

Habiyaremye also gave a few seeds to his mother. It grew faster than expected, and neighbors soon became curious.

"From there, we started to see a lot of interest from farmers," Habiyaremye says. "We were blown away... initially we didn't know if people would accept it."

Habiyaremye partnered with Rwanda's Minister of Agriculture to bring more quinoa into the country and train farmers on how to grow and cook it.

The program had about a dozen farmers in its first year. Today, Habiyaremye says there are close to 1,000 farmers.

"The number has been growing like crazy," Habiyaremye says.

Farmers in Rwanda don't usually have grain elevators to keep their harvested crops out of reach of insects, which often means they have to use pesticides to protect their harvest. But quinoa has natural protections from bugs, which helps farmers there save money and avoid using harmful chemicals, he says.

Habiyaremye graduated from WSU in 2019 and has continued to work with the university and study how the quinoa plant grows in Rwanda.

He has recently been collaborating with researchers at WSU and Brigham Young University to develop new varieties of quinoa that thrive in diverse climates. The work was started by researchers at BYU, who developed close to 1,000 breeding lines and sent them to WSU for experimentation.

From there, Habiyaremye worked with researchers at WSU to identify the best-performing seeds and took them to Rwanda for further testing. They found the quinoa varieties that performed best in Rwanda originated in Ecuador, which is similarly close to the equator.

Last June, the researchers announced the release of three new quinoa varieties: Shisa, Gikungu and Cougar.

Shisa quinoa is specifically designed to thrive in Rwanda's high-altitude regions. It matures slightly earlier than other varieties. The name was chosen by farmers, Habiyaremye says, and means "to flourish" in Kinyarwanda, one of Rwanda's official languages.

"They chose this name because they say quinoa has improved their lives and the lives of their children and helped them grow and develop in a healthy and vigorous way," Habiyaremye says.

Gikungu is designed for low altitudes. The name means "economy" in Kinyarwanda, and Habiyaremye says local farmers chose the name because of the role quinoa can play in economic development.

The third strain, "Cougar," was named by researchers at WSU after the school's mascot. Cougar quinoa has distinctive, vibrant red seeds and bright green leaves. It's a bit of a mix of Gikungu and Shisa because it can thrive in both high and low altitudes.

"We want to develop a system where quinoa can be among the staple foods in the country," Habiyaremye says.

Through his company, QuinoaHub, Habiyaremye is continuing to help train farmers on how to grow the plant. He's recently expanded to eight other countries in Africa and is working with Rwanda's Minister of Agriculture to develop a national quinoa distribution system.

In addition to the nearly 1,000 farmers now growing quinoa through his program, Habiyaremye says other farmers have obtained seeds from participants in the program and are now growing quinoa independently.

"With all those, we can't track the numbers, but we know that they have also grown," Habiyaremye says.

Many crop seeds are patented, which means the companies that create those strains maintain control and receive royalties off all seeds that are sold. But Habiyaremye says the three new quinoa strains are open source, which means anyone is free to use and share them.

Quinoa should be used for the "greater good of humanity," Habiyaremye says, not to "just squeeze a penny out of a poor person.

"We don't want to make quinoa a cash crop." ♦