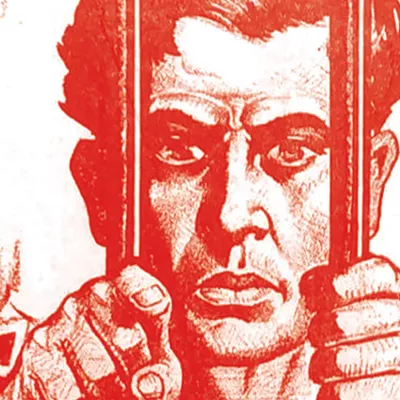

Chris Tennant will never forget the night of the Washington State University riot. He'll never forget the screams of hundreds of college kids surrounding him, or the rocks they threw in fury. He'll never forget how the flames from the fires they set to Greek Row reflected in their eyes.

That night, just after midnight May 3, 1998, he and other Pullman Police Department officers were surrounded by rioters attacking with anything they could get their hands on. Tennant got hit with a cast-iron pot. He thought his leg was broken, and he feared for his life. He saw one person nearby smash an officer's leg with a manhole cover. When the officer made it to a patrol car, somebody else threw a cement brick at the car, shattering the back window.

"And all for what?" asks Tennant.

It wasn't a protest of war, or societal injustice. The Washington State University riot in 1998 centered around one thing: the right to drink beer.

Tensions between WSU students, the school and local police were heightened that year, due to a WSU ban on on-campus and fraternity drinking, part of a nationwide crackdown on alcohol in colleges. And around 12:30 am May 3, 1998, officers got a call that a person had been hit by a car in the middle of Greek Row. When police arrived, no injured pedestrian was found. But, as it was the weekend, there was a keg party nearby.

Apparently, as Tennant recalls, the partygoers thought police were there to shut it down. And on that night, they weren't about to let that happen.

They threw rocks and beer cans at police. Police promptly called for backup, but it only emboldened the partiers. They threw garbage and portable toilets into the street and lit them on fire. The number of rioters grew to about 200, with hundreds more looking on.

By 2 am, police decided they needed to take more serious action to stop it. They called for dozens of Whitman County officers, 18 state troopers and officers from Moscow, Idaho and Latah County.

They tried to use tear gas to disperse the crowd, but it backfired, only fueling the crowd even more.

Tennant says they would have been justified in using lethal force, but they held back. They didn't want anything like the Kent State shootings.

"At the end of the day, even though we were dealing with a mob, they were all college kids," Tennant says.

Luckily, everybody came out alive. Four students and 23 officers were treated for injuries. Police and WSU investigations resulted in a few students being expelled, and 19 convicted of a crime, mostly misdemeanors. Pullman officers left the department. Officers across the state got more training on how to handle riots. And today, alcohol is still prohibited in many places on campus, permitted only in some cases where students are of legal age and in the privacy of their own room.

But most importantly, Tennant says, after the riot came a new emphasis for police on communicating with students. Pullman police created a program that had officers get to know students on College Hill.

"The idea," Tennant says, "is it's a lot harder to beat up on friends than strangers."