No matter what’s done, the guy on the table isn’t going to care. The surgery that’s about to be performed can go well, or it can go completely wrong and there won’t be any lawsuit. He’s not going to be concerned about scarring or recovery.

That’s because he’s dead. And someone is about to learn from his cold body.

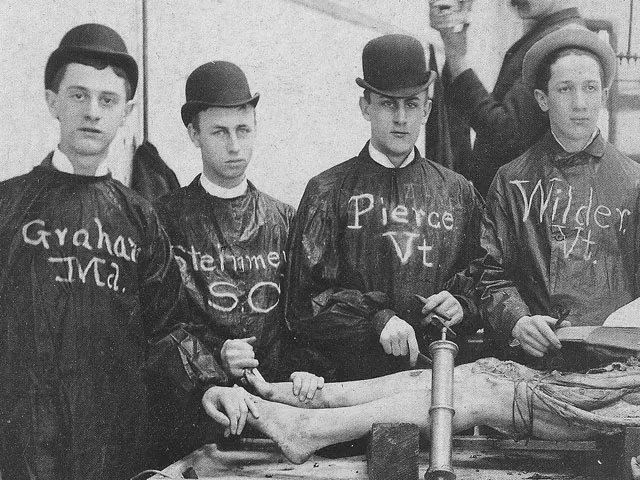

In Dissection, you’ll take a fascinating peek at the history of Anatomy & Physiology classes from a century ago. And you’ll be thankful that you live now.

“During the nineteenth century, the experience of dissecting a human body was more prominent in the education of American doctors than any time before or since,” says John Harley Warner in his introduction.

Back then, many doctors learned their craft by apprenticeship, and a chance to view the inner workings of the human body was precious. Then, as now, students looked upon cadaver dissection nervously — as they would with any important rite of passage — and professors cautioned them to keep in mind that the body used to be a living human being with loved ones.

To procure bodies, grave-robbing was all too common; at least, until the deceased relative of a former president showed up on a table. Later, unclaimed bodies made their way to A&P classes and the occasional generous donor came under the knife.

As you page through Dissection, several things slowly dawn on you. First, amazement that med school students actually made Christmas and Easter cards and postcards with photos of cadavers in various degrees of flayed. Second, surprise that large numbers of African-Americanonly and women-only medical school classes existed in the 19th century. And finally, discomfort over how gowns were few, masks were completely lacking, decomposition must’ve been ferocious, and latex hadn’t been invented yet. Nobody was gloved.

Warner and Edmonson point out that several medical school students died of infection contracted from the corpses from which they were learning.

Dissection, then, is not for the faint of heart. But it’s a fascinating peek at our medical past.