In last week’s cover story about family history and how the Internet is changing the way we search, I wrote about how my grandmother’s father was born in Texas and ended up in Spokane.

Initially, though, I was researching my grandmother’s maternal grandfather, Howard Parrish, who came to Spokane as a young man and died at 88 in 1955. He was a Baptist preacher by the end of his life, and he was the one who walked my grandmother down the aisle after her own father died when she was young. According to family story, and his obituary, he worked for both the police department and the fire department during the early days of Spokane.It was through Google News Archive online that I found a tantalizing paragraph: In a Spokane Falls Centennial retrospective published by the Spokane Chronicle on Nov. 26, 1981, Howard Parrish is mentioned in a story called “Hardy pioneers came, seeking their fortunes”:

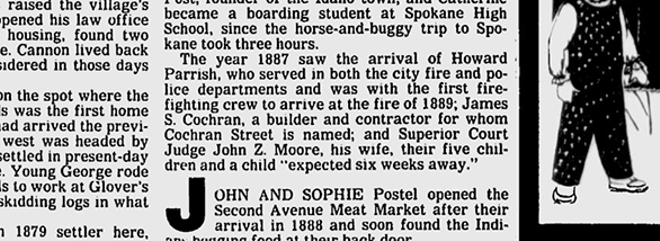

“The year 1887 saw the arrival of Howard Parrish, who served in both the city fire and police department and was with the first firefighting crew to arrive at the fire of 1889…”

If true, that would be a remarkable thing. The early history of Spokane is split by the fire — the insurance money that poured in afterward transformed the railroad hub into a boom town. It tells you something, what side of the fire your family showed up on.

There are no sources listed in the story. I Googled combinations of other names in the article and found no uniting source. I Googled the writer and found her obituary.

So I tried to find out: Was Howard Parrish present at the Spokane fire of 1889?

THE LIBRARY

My first stop was the third floor of the downtown library, where volunteers from the Eastern Washington Genealogical Society help people with research every Tuesday afternoon.

We start with the federal census records available online free from FamilySearch, which show that in the 1880 census Howard is 13 and living with his parents and older brother, Charles, in Pennsylvania. In 1900, he is listed as 34 and living in Spokane on Gardner Avenue with his wife, three children and his in-laws.

There is no 1890 census. As I mention in the story, the 1890 census was almost entirely destroyed in a fire, which leaves a huge hole in history. This is a good example: A huge amount of life happens in the two decades between 13-year-old Howard living with his parents and 34-year-old Howard married with kids.

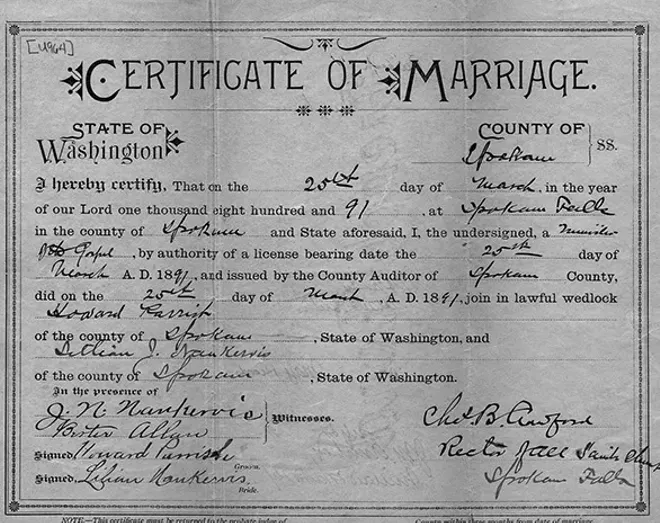

Fortunately, there are other resources: The Washington State Digital Archives has the record of his marriage to Lilian J. Nankervis in Spokane on March 25, 1891, among other records.

So he was definitely in Spokane by 1891. Next we turn to the city directories, which are essentially phone books before people had phones. They often list address and either occupation or employer, and they often have handy maps and other contemporary information. Spokane’s first was in 1885, when the city was still called Spokane Falls.

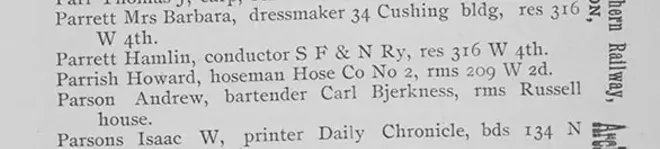

Howard Parrish first appears in the 1890 directory, as a hoseman with Hose Co. No. 2. The corresponding fire department roster in the city directory indicates that he was a driver.

In 1893, he is no longer listed with the fire department. In 1895, he is listed as a driver with Cascade Laundry, and the following year as a warehouseman. In 1900, he is listed as a patrolman with the police department, living at 2028 W Gardner Ave., the home in West Central where he lived the rest of his life. He is listed with the police department in each directory until 1907, when he became a collector for a Seattle-based furniture store.

(One confusing thing that keeps comes up when searching is that another Howard W. Parrish lived in Spokane during the early 20th century. Additionally, a Howard W. Parrish became the owner of the Seattle Star in 1942.)

We look up the 1887 Spokane County census on microfilm; he is not listed. That doesn’t mean he wasn’t here — it just doesn’t prove that he was.

THE POLICE MUSEUM

It was recommended that I get in touch with the Spokane Law Enforcement Museum, to see about any other information from the city’s early days. So I headed over on a Tuesday afternoon, and brought a photo of Howard Parrish that my mom once sent to me on my phone.

The volunteers there took a look at the photo and the dates and brought out a book they’ve republished from the original version. It’s a yearbook, essentially, published in 1902 to raise money for establishing a pension and relief fund for police officers in Spokane. Sure enough, on a roster page, the name H.W. Parrish is listed.The book includes many photos, but not one of him. They pointed out the drooping mustaches on most of the faces and told me it was unusual for a policeman to be clean-shaven at that time. And his hat — that style indicates that he was a wagon driver. Glen L. Whiteley, the museum’s founder and curator, pointed out an old photo on the wall of a wagon crew with their horses at about that time. Wagon drivers were responsible for the horses back then — caring for them, and training them to stay calm while running toward trouble.

I peered into all the tiny faces in the framed photos covering the walls, but none were familiar.

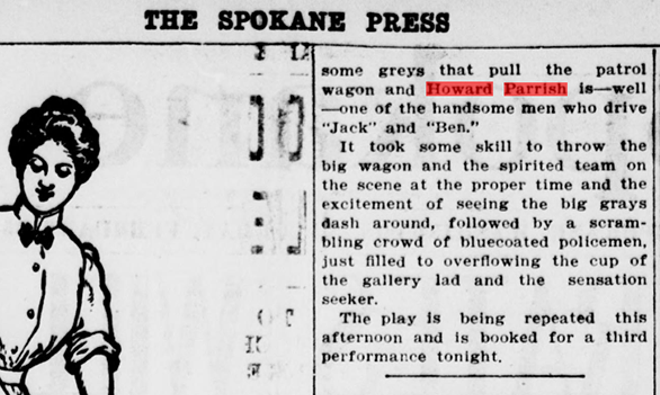

Later, searching through the excellent Library of Congress collection of historic newspapers, Chronicling America, I did come across a 1905 Spokane Press article about about Howard Parrish and his horses, Jack and Ben. They were apparently performing at the Auditorium Theater, located where River Park Square is today, for a play called “The Police Patrol.”

“‘Jack’ and ‘Ben’ are the handsome greys that pull the patrol wagon and Howard Parrish is—well—one of the handsome men who drive ‘Jack’ and ‘Ben.’ It took some skill to throw the big wagon and the spirited team on the scene at the proper time and the excitement of seeing the big grays dash around, followed by a scrambling crowd of bluecoated policemen, just filled to overflowing the cup of the gallery lad and the sensation seeker.”

THE NORTHWEST ROOM

Everyone I talked to kept saying I should visit the Northwest Room at the downtown library, to see if its trove of amazing regional materials might have additional clues.

There, I explained my search for fire department records or accounts of the fire, and I ended up with a stack of books and materials. I pored over maps of the fire and read transcripts of eyewitness accounts of the fire.

I read that it was a calm, warm summer evening when the fire started, and how a problem with the city water works meant water only trickled from the hoses. I read the oral history account of the fire from Lloyd E. Gandy, who was 12 when he watched the city burn from his front porch until his mother made him go to bed. I read how the bell in the fire tower rang until it melted.

I looked at an original copy of the book they showed me at the law enforcement museum, and learned that Hose Co. No. 2 was established in 1884 and entirely destroyed in the fire. I read that the fire horses knew that the next stop, after leaving the scene of an extinguished fire, was the brewery.

I never once came across the name of Howard Parrish. His name is not listed in the 1893 city council ordinance creating an official Spokane Fire Department. His name is not mentioned in a reunion of firefighters a few decades later.

An old newspaper clipping showed the obituary from James E. Daniels, the last of the “volunteers from ’89.” He died in 1945, a full decade before Howard Parrish. In another article I found later in the WSU Libraries Digital Collections, from 1936, Daniels recounts the fire and lists a few others from the old hose company still living. Howard Parrish is not among them.

THE SEARCH CONTINUES

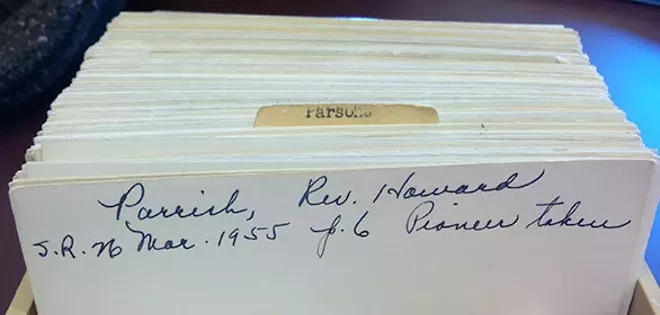

In retracing some of my steps to write this, I realized I never did look back at the second article handwritten on a card in the Patchen file, a brief obituary story published on March 26, 1955, in the Spokesman-Review.

I look it up online in Google News Archive:

“Mr. Parish came here in 1887 and helped battle the first [fires] which almost destroyer [destroyed] the downtown area in 1889. In the early 1900s he served on both the city fire and police departments.”

Apparent typos aside, this is probably where the information in that Spokane Chronicle article came from. Which solves one mystery, probably, though not the main one.

I’ve by no means exhausted all lines of inquiry; but I had a deadline, and it became clear that the answer wasn’t going to come easy. There are payroll records and other paperwork I could try to find. I could look more thoroughly for contemporary accounts, and try to figure out what stories have been passed down to more distant cousins.

The most frustrating aspect of searching into history is that there is a correct answer — either it happened or didn’t. Either he was there or he wasn’t. At one point these answers were known to someone; we had them, and we might not ever know again.