The grass is greener on the south side of Bridge Avenue. A squadron of GreenLeaf Landscaping workers in fluorescent vests are on patrol in Kendall Yards, where the rectangular lofts and sharp-angled townhomes are painted in rich shades of modern gray.

They're armed with mowers and leaf blowers, ensuring every house has a lawn up to the same exacting standards. Horticulturists, weed sprayers and irrigation specialists descend on the neighborhood, caring for the daffodils, the feather reed grass, and the young trees that are spaced along the sidewalks with mathematical precision.

The pristine yards and porches of Kendall Yards seemingly vary only by the brand of high-end barbecue grills and deck furniture preferred by owners.

But on the other side of Bridge Avenue, which runs east-west, the carefully coiffed Kendall Yards neighborhood becomes the wilder West Central. Some West Central lawns have watered grass and trimmed flowers, sure. But there are also the yards where shin-high weeds grow untamed, and the yards that are nothing but dirt. There are the bare yards strewn with toppled Tonka trucks, plastic bowling pins and naked dolls missing limbs.

Fraying Tibetan prayer flags are strung above one porch, as chickens peck at the grass. A rickety wooden chair with "I love Jesus" crudely painted in red on the back is perched on the porch next door. Stray cats lick at the water in a plastic tin in an overgrown yard, next to a house where kids scurry around overturned bikes and Big Wheels.

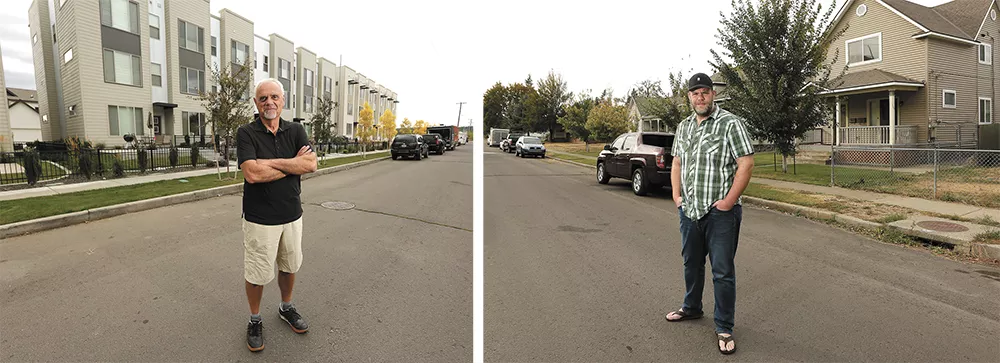

Jim Frank, Kendall Yards' developer, rides through Bridge Avenue on a golf cart, Kendall Yards on his left, West Central on his right. On the left, the tony, three-story Solo Lofts condos were snatched up for $200,000 — six sold in a single day in April, even before they were built. The new condo owners stare across the street at an abandoned home with peeling paint and boarded-up windows.

That, Frank says, is intentional.

"We wanted them to face the street, even though often what they were facing often wasn't very pretty," Frank says. "We wanted Kendall Yards to be part of West Central."

But the separation remains stark. The houses on the right are often 100 years older and sell for $100,000 less than the houses on the left. West Central is one of the poorest neighborhoods in Spokane — and Bridge Avenue is in one of the poorest parts of West Central. So when the 78 acres of former rail yard to the south began to transform into the high-end Kendall Yards development, the surrounding neighborhood was expected to transform with it.

So far, the north side of Bridge Avenue has largely resisted that transformation. Frank sees sparks of investment, but not the strong, fast change he'd been hoping for. Over the past year, more properties on the West Central side of Bridge have seen their assessed values fall, not increase. As the market heats up and Kendall Yards' construction marches westward, that could soon change, but for now, Bridge remains a symbolic and literal dividing line, separating the new from the old, the rich from the poor.

SEPARATION ANXIETY

The divide on Bridge Avenue could have been even more stark. Developer Marshall Chesrown's original vision for Kendall Yards, in the heady days of 2007's construction boom, featured more density, higher prices, taller buildings and swankier condos. It was planned as $1 billion gated oasis of high-end luxury in a desert of poverty.

"The previous potential developer, Chesrown, he was like, 'Ugh, we're going to build a fence. And that all the houses will face each other and you don't have to look at the poor people,'" says West Central resident Bea Lackaff.

The economic crash, however, destroyed Chesrown's plans, leaving Jim Frank's Greenstone Homes company to swoop in and pick up the pieces.

Frank had a different plan. He imitated the existing street grid of West Central instead of turning the whole thing into a network of cul de sacs. He capped building heights on Bridge to create a smoother transition into West Central.

"Bridge isn't anything special. It's not a barrier. It's not a boundary. It's not like the end of our project and the beginning of something else. We're all one neighborhood," Frank says. "Bridge is nothing but another street."

At least that's his long-term vision.

To assist that integration, Greenstone has poured much of its own resources into West Central. Neighborhood activists praise Greenstone's contributions to the neighborhood council, Project Hope, a nonprofit that involves kids in community gardening, and West Central's C.O.P.S. (Community Oriented Policing Services) location.

"My fear was the people living in Kendall Yards would want to isolate themselves from West Central," Frank says. "But that's the furthest from the truth. They've wanted to do what they can to be part of West Central and help West Central."

Frank notes that Kendall Yards neighbors cook a monthly meal for the community at West Central's Youth for Christ center. Some of them have helped their West Central neighbors with landscaping. Kendall Yards resident Kathleen Grier says she volunteers at the Spark Central — a Greenstone-supported nonprofit that focuses on literacy for West Central kids.

Three years ago, Marshall Peterson, who lives above the art gallery he runs in Kendall Yards, launched a music festival called Porchfest, precisely as a way to bridge the class divide between West Central. Greenstone sponsored it.

Kendall Yards neighbors speak of friendships forged across the street.

And neighbors on both sides say they've seen the crime begin to fall in the neighborhood once disparaged as Felony Flats.

"When I first moved in, it was a kinda sketchy neighborhood. Like 3 am to 5 am, there'd be some very criminal-looking people roaming up and down the street," says West Central renter Kevin Doyle. "There'd be some guy with a bicycle with a baby carrier behind him, and all those criminal tools in the baby carrier."

But the neighborhood has changed since then, he says. It feels safer.

"The simple answer to crime is people," Frank says. "You do some investment here, and you put people in the street, and crime goes away."

Police data seem to back that up: According to Spokane Police Department statistics, the amount of crime in the district that includes West Central fell nearly 25 percent between 2012 and 2015, outpacing the drop in crime citywide.

Yet crime can also become a flash point between the two sides of the street.

Mike Brakel, chair of the West Central Neighborhood Council, says he's seen tensions flare up on Nextdoor.com, a social network that puts West Central and Kendall Yards on the same private forum. Kendall Yards residents sometimes blame West Central for burglaries. Brakel scoffs at the new neighbors who feel they can just leave their garage door open and expect nothing to happen.

West Central residents bristle at feeling judged, he says, feeling like Kendall Yards residents don't understand what it's like to live in generational poverty.

"There does seem to be an 'us vs. them' mentality," Brakel says.

At times the separation is explicit: As Oak Street turns into the driveway at the back of the Kendall Yards apartments, a red-on-white sign warns "Private Access Residents & Guests Only."

Lisa Lightbody lives with her kids, her sister and her sister's kids on the West Central side of Bridge, all struggling to get by.

Lightbody yells at her niece to stop doing cartwheels across the street in Kendall Yards.

She says some Kendall Yards residents are nice — entertaining her kids, even giving them snacks — but not all of them. "The ones that are not nice will just drive by slowly and give you dirty looks, pretty much like you're not a person," she says.

Lightbody's 10-year-old daughter gleefully interjects with a theory: "Because these houses are ugly," she says. "I think we should rebuild this whole street!"

Holly Garrabrant, a pastor with a West Central street ministry, says class resentment exists on both sides. Some low-income residents view Kendall Yards as almost a colonization, contemptuously referring to it as the Gaza Strip.

"There is a large income discrepancy as well a cultural barrier of fear," Garrabrant says by email. "The people who grew up in West Central have had several encounters with residents of Kendall Yards that were unpleasant, fear-based, and at times racially motivated."

Garrabrant describes breaking up a confrontation at the new park in Kendall Yards, where a Kendall Yards resident pulled a knife on a West Central resident, telling her to go back to her part of the neighborhood.

"[Kendall Yards residents] drive expensive cars through areas of West Central where people live 12-to-15 deep in two-bedroom apartments, scrounging for things like deodorant, borrowed shower and laundry services," she says.

Garrabrant and Brakel both see ways that Kendall Yards neighbors could get more involved. He says Kendall Yards has accountants who could help residents with their taxes, and lawyers who could give them legal aid.

Brakel would like to see a big public forum, possibly moderated by the city, that would bring together Kendall Yards and West Central to talk through their issues. Technically, the city considers the two part of the same neighborhood — though only one Kendall Yards resident is on the council.

"The cultures are so complexly different," Brakel says. "Neither side really understands where the others are coming from."

ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT

A rusted horseshoe hangs above the numbers — W. 2312 — fading on the concrete porch. The paint on the side that hasn't sloughed off has faded to the color of old newspaper. The cracked front window has been plugged with caulk, but a jagged hole has been busted in the attic window. That may be how the pigeon got in: The bird bobs and struts through the dust and rubble on the concrete floor, underneath bare wooden beams, then flutters up into the rafters.

This vacant Bridge Avenue house is owned by Gavin Cooley, the chief financial officer of the city of Spokane. The struggles he's had with the property illuminate why despite — or even because of — Kendall Yards, improving the neighborhood has been so slow.

Cooley says he bought the house in 1998. He'd look at the bare land across the street, and picture the thriving neighborhood that was sure to someday be built there.

But then a once-reliable long-term tenant went downhill. Court records and an interview with the tenant reveal a sad and ugly tale involving emotional health issues, custody battles, property destruction, an abusive ex, a bipolar boyfriend and a methamphetamine arrest. Cooley says he waited too long to evict her, and by the time she was out the house, it was utterly destroyed.

"All I could do was take it down to the studs and wait for the opportunity to reinvest," Cooley says.

He's been waiting eight years.

The whole thing has been a nightmare. Squatters have repeatedly pried plywood off of his windows or kicked in his back door, using the empty house as a warm place to sleep. For a few years, the next-door neighbor was looking after the property — until 2009, when two drunk teens beat that neighbor to death so viciously, cops identified one of them by the footprint he left on the neighbor's face.

In 2012 and 2013, confidential complaints about Cooley's property were sent to the city. "Garbage — couch, etc. Blocking driveway," one complaint says. "Garage door open. Nuisance."

"Mattress, box-spring and piles of clothes in the alley!" another reads.

The city cracked down. The office of Code Enforcement — one floor below Cooley's in City Hall — sent him multiple letters about solid waste and fire hazard violations, with boxes checked like "garbage and refuse not in cans," "Unsanitary condition — risk to public health or safety," "public nuisance: No appeal."

And the garbage problem hasn't ceased. Cooley says he recently filled an entire dumpster with the trash — a mattress, a sofa, a TV — that someone dumped into his yard.

"When you have an abandoned home — or a seemingly abandoned home — it has a huge deleterious effect on the surrounding neighborhood," says Cooley's colleague Jonathan Mallahan, the city of Spokane's neighborhood and business services director. Particularly when there's the presence of garbage, he says, a vacant house can send the home values of neighbors plummeting by as much as 17 percent.

The West Central side of Bridge has at least three such vacant homes.

Cooley's house lost nearly $8,000 in assessed value this past year. The Kendall Yards townhomes directly across the street, meanwhile, sold during the same period for more than $200,000.

Still, Cooley is wary of spending tens of thousands of dollars to bring the house up to snuff, doubting that he'll be able to justify a higher rent if the neighborhood doesn't improve first.

Keith Johnstone, who owns the house next door, says he's also waiting to invest until the other houses improve. "There's no bold leader out there," Johnstone says.

It's a recipe for stalemate: Many of the West Central homeowners don't want to improve their properties until their neighbors do. But since Kendall Yards represents a promise of significantly higher home prices, a lot of West Central owners have delayed selling.

"Like a lot of people along there, I'm waiting for the best return on investment," Cooley says.

Fewer West Central houses have sold on Bridge Avenue in the seven years since Frank announced his Kendall Yards development than in the previous seven years. Some of that is undoubtedly a consequence of the recession. But it also could be the fact that over the past 25 years, the possibility of developments like Kendall Yards has been dangled time and time again in the area, sparking speculators to snatch up properties and wait. In the meantime, some of those homes have crumbled.

At this month's West Central Neighborhood Council meeting, Arielle Anderson, a West Central resident, tears into the problem of substandard homes there.

"Folks should not be living in that. We should be absolutely appalled and embarrassed that people live in the type of housing they live in, in our own community. That we allow that to happen," she says. "I want the city to step in and start reining this shit in. Because it's just absolutely appalling what we see."

In fact, the city has made this issue a major priority. Just last week, the Mayor's Housing Quality Task Force presented its suggestions for how to improve the houses in neighborhoods like West Central. Already, the city has changed the way it responds to troubled properties, using tax liens and incentives like single-family home rehabilitation loans to spur landlords to either improve their properties or sell.

Next month, Spokane's Neighborhood Services division and the nonprofit Spokane Neighborhood Action Partners will go door to door in West Central, explaining to residents how the city can help them in anticipation of a neighborhood-wide cleanup day on Oct. 21.

"I believe the city is moving in the right direction," says Anderson. "We just need to see action, sooner than later."

But Frank says that city regulations currently restrict West Central from transforming in the same ways as Kendall Yards.

"The thing that frustrates me is that what you see constructed there on this side of the street, as you go down, cannot be constructed over here," Frank says, pointing from the Kendall Yards side to the West Central side.

Kendall Yards' planned unit development agreement lets it divide up lots into small segments and sell townhouses close together. But most West Central property owners would have to wind their way through an expensive and arduous hearings process to do the same. It's a regulatory system, Frank argues, that favors rentals and creates all kinds of barriers to homeownership.

And that's a huge part of the problem. Right now, he says, about 60 percent of West Central's houses are rentals, compared with 40 percent in the rest of the city.

"It's totally out of kilter," Frank says. "You're concentrating all of the rentals and all of the low-income living all in one place. It's not good."

He says the consequences for the neighborhood are awful. For neighborhood schools like Holmes Elementary, he says, it creates chaos: Many of the kids in the classroom in September have moved away by June.

"You don't realize how debilitating it is, losing that social structure in a neighborhood," Frank says. "From my point of view, nothing can be worse than what is going on right now."

BRIDGE TO THE FUTURE

Bags of popcorn rest on the bright orange statue of a vintage camera as a Porchfest musician strums his acoustic guitar outside a West Central home. In the past year, the value of this home shot up nearly $45,000, more than any other single-family home on Bridge. It's obvious why.

The homeowner, photographer Nick Follger, speaks with a German accent, describing how he and his wife wrestled with how to remodel their house while respecting West Central's century-old character.

"By taking an old home, and trying to make it more modern and energy-efficient, would we be sticking out in the rest of [the] homes — as an intruder, maybe?" Follger says. "We spent many, many months trying to figure out how to go about it."

They decided to aim for a blend of the old and the new. The balcony and modern framing and gray color scheme matches the Kendall Yards homes across the street, but the angles and footprints imitate the West Central houses next door.

And as new Kendall Yards condos rise up to the west, others have begun leaping into the fray. Real-estate investor Patrick Kendrick — a West Central resident himself — just purchased two duplexes on Bridge Avenue, the property with the off-white siding and the flamingo stuck in the dead lawn. He plans to repaint it, mimicking the Kendall Yards color scheme right down to the paint codes.

"Down the road, I plan on using the same landscaping, the same fencing, all of it," Kendrick says.

That there hasn't been more improvement in this area, Kendrick says, "boggles the mind." But he views the whole neighborhood through the lens of optimism, pointing out the spots that have recently been sold or rehabbed. He points to a house that, if you look past the chipped paint, shows proof of a real pride in ownership.

"If they painted that thing, it would be gorgeous," he says.

Just as a vacant property can send values plummeting, Kendrick believes that a single improved property like Follger's can have the opposite effect, setting off a cascade of improvements in other properties.

When he looks at Cooley's property, he doesn't see a nightmare. He sees possibility.

"Wow. That's a great property," Kendrick says. "Does he want to sell it?"

Cooley says that he and his wife are talking about it. Next year is the time to finally make a decision, Cooley says: Reinvest or sell. And if there's any time to sell, it's right about now.

Citywide, a real-estate boom has sparked a flurry of home buying and constrained the rental market, driving prices higher. But what's good for property owners isn't always good for low-income renters. Brakel, the West Central Neighborhood Council chair, says he's concerned about gentrification: Improve property values too much, and suddenly it's not just changing the neighborhood — you've changed out the neighbors.

"It's a horrible situation to try to struggle and keep this balance between improving the community for those who reside here, and making it an opportunity where they can still reside here," Brakel says. "It means displacing the residents of the neighborhood. It means basically making people homeless."

Kendrick says he's not a big fan of the word "gentrification."

"'Revitalization' is probably a better way to put it," says Kendrick, who sees real-estate investing as an evolution of his community activism. He's long been active with local arts groups and has worked for the Inlander's Volume music festival.

Still, as in Kendrick's new property, the side effects of that revitalization can be seen.

Back in 1995, Shawn West moved into the small one-bedroom apartment at the top of one of Kendrick's duplexes. He was 20. "I moved to Spokane in the early '90s, because you could have one job, no roommate and have your own place," he says.

West was there when the house flippers who previously owned the building got over their head during the recession. He was there when the bank foreclosed on it. He was there when the owner's other property on Bridge burned down, and weeds grew in its place.

Today, at 41, he's leaving the apartment for Spokane Valley.

He was only paying $350 for rent — but Kendrick plans to raise it to $500. That's still cheaper than the median amount for a one-bedroom Spokane apartment in this booming market, but West says it's impossible for him to afford that price on his salary from a local machine shop.

"I don't know how you can pay out that much in rent and still have anything left," West says. "I don't have a cellphone, I don't pay for TV."

Joshua Godfrey, a 20-year-old who'd been renting the top unit in Kendrick's other duplex, piles his snowboards and skateboards on top of his other belongings in a pickup truck. He's moving to a run-down neighborhood near NorthTown Mall where a Papa John's delivery boy salary can pay the rent.

"It's not as nice, that's for sure," Godfrey says. "It's life, man. It happens."

The excitement about how Kendall Yards could change West Central is tempered by caution, even nostalgia. Follger says his latest photography project is to try to capture the old West Central before it's gone forever.

"There is going to inevitably be tremendous change happening in this neighborhood," Follger says. "West Central will change, some of it for better, or for worse. Right up the street... we saw that whole block being taken down for a car wash. That was for worse."

That, he laments, could have been turned into a new block with new houses.

Greenstone's recent announcement that it would build its own local grocery store came stocked full of Kendall Yards-friendly phrases like "locally sourced" and "sustainable agriculture" and promises of wine clubs and cooking classes. But West Central residents like Anderson hope that the store's prices would be affordable for low-income West Central residents, who are currently in a food desert without close access to a grocery store.

Frank says to expect the prices of some items to be more expensive, but that much of it will be competitive with stores like Fred Meyer. "We hope to be able to serve a lot of West Central," he says. "It's a mistake to think that West Central is made up of nothing but very poor people."

Neighbors like Anderson look at Spokane's Perry District in the similarly impoverished East Central neighborhood. While some celebrate it as a model of the promise of revitalization, Anderson sees it as an example of the peril. She says she'd considered moving to Perry, but was completely priced out.

"Gentrification gone completely wrong, right?" Anderson says. "Normal working people can't afford to live there."

Kendall Yards sales manager Cat Carrel says that gentrification is inevitable. In five years, Greenstone will have built out on all the vacant land in Kendall Yards, and the only way to be a part of the development will be to buy across the street.

Frank isn't concerned. He's excited about the change.

"The world doesn't stay the same," he says. "If I don't create an environment where there's some investment in my neighborhood, it's going to get worse. I want West Central to get better."

And someday soon, he hopes, the dividing line between Kendall Yards and West Central will disappear completely.

"The perfect world — my ideal — is that 20 years from now, no one knows," Frank says. "They drive through here and have no idea where Kendall Yards started and ended." ♦