Idaho often has been overlooked by those dreaming of moving to the great Northwest. No more. The state population of 1.8 million is growing faster than any other in recent years, adding 256,167 residents (16.3 percent) from 2010 to 2020.

A natural question arises about one of the reddest states: Is growth changing its political profile? It is, but not in the way you might think. It's growing meaner, sillier and more small-minded.

I moved from Seattle to North Idaho 20 years ago. When confronted by liberal family and friends with raised eyebrows, I responded with a simple declaration: "I'm not moving there for the politics." My husband and I had long vacationed at a cabin on Lake Pend Oreille and, smitten by the peaceful lifestyle, rural acreages and small-town charms of Sandpoint, planned our retirement there. Today we enjoy a busy life on 25 acres with two gardens, a horse, a pen where we raise lambs, and a flock of hens that lay the prettiest brown and blue-green eggs. In the fall and spring, we clean up the forest and burn the slash piles. That was the life we imagined.

What we didn't imagine was finding ourselves in what we now call "the blue nation of Glengary," a collection of neighbors spread along a two-mile band of wooded acres and lakefront homes. The scenery is matched by the quality of friendships we've made. We don't talk politics much, but over time these good friendships reveal shared values about protecting the lake's water quality and the importance of electing reasonable people to the county commission, the school board and the state Legislature. Last fall there were plenty of Trump signs in the area, but I was pleased to see a Biden flag added flying below the American flag on my neighbor's pole.

This is not the Idaho most people imagine, and it is not representative of Idaho — old or new. My neighborhood is a tiny blue puddle in a sea of red. For all the talk (hope?) that the influx of newcomers would moderate the politics of Idaho, the opposite is the reality.

The last Democrat to win an Idaho presidential election was Lyndon Johnson in 1964. Kootenai County in North Idaho is a population growth hotspot. It is home to Coeur d'Alene and site of a successful organizing effort by far-right conservatives in recent years. Its margin for Trump last fall was 43 points. In the state as a whole, Trump bested Biden by more than 30 points.

I started my newspaper career in Boise in the early '70s and for several years covered the Idaho Legislature. Republicans dominated, but nothing like today. To my inexperienced eyes, the place seemed largely respectful of differences in politics. A few Democratic leaders managed to wield influence, but one Democrat outdid them all: Cecil Andrus was governor, and that made all the difference. Andrus served from 1971-77, when he left to become Interior secretary in the Jimmy Carter administration. A sign of Andrus' enduring popularity in the state was his re-election after the stint in Washington, D.C. — two more terms, which ended in 1995. This was also the era of Sen. Frank Church, elected in 1957 and defeated by less than 1 percent of the vote in the 1980 Reagan revolution. No Idaho Democrat has served in the U.S. Senate since.

Church and Andrus are legends of Idaho political history. They came to power when labor unions flourished in North Idaho, where mining and timber dominated. All that began to change in the '70s when I was covering the Idaho Legislature for the Idaho Statesman and later Idaho Public Television. Liberals across the country were embracing environmental causes and cultural issues — feminism, abortion, anti-war. These causes didn't play well outside liberal Boise. Elsewhere, Mormons and conservative values prevailed. At the same time, traditional, unionized industries related to mining and forestry were declining. Idaho chugged along with its Republican political base until a decade into the current century when population growth due to in-migration began to alter the dynamics.

Voter registration numbers tell the tale. Republicans consistently register more new voters than Democrats, especially in the areas of greatest growth. The result was a huge gain for Republicans by 2020, with 53 percent of voters registering Republican to just 14 percent for Democrats.

This swing to the GOP in the Trump era is obvious in the current Idaho House of Representatives, where some crazy stuff is going on. Lawmakers rejected a federal grant of $6 million for early childhood learning. One lawmaker opposed it because he believes mothers should be at home with preschoolers. Others worried that the curriculum would push a "social justice agenda" on Idaho's little ones. Early education funding lost by two votes. Idaho is one of only six states that does not fund any early education and one of many states now fearful of a so-called "social justice agenda."

Rep. Heather Scott, one of the best known and most conservative members of the Legislature, is from my region of North Idaho. She gained attention a few years ago for traveling to the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge to meet with Ammon Bundy. In the current legislative session, she helped to end Idaho's involvement in Powerball, which brings in money targeted for education. Why? Because it's now being expanded to Australia, and Scott, who is staunchly pro-gun, fears the Aussies would spend Powerball money on anti-gun causes.

Last month I sent an email to Sen. Carl Crabtree, a Republican, who represents me in Boise. I knew him to be a reasonable fellow and said I hoped he would vote against a bill that would make it virtually impossible to pass citizens' initiatives. Two years ago, an initiative to expand Medicaid in Idaho was successful, and conservative lawmakers, still stinging, were determined to head off a new effort that would increase education funding. (Idaho is 50th in the nation for per pupil spending.) Crabtree said he did not intend to vote for the bill. Two weeks later I saw that he had voted in favor. I emailed again. He responded promptly and said he had received additional information. "My opinion is with you, my vote was with the plurality of my constituents," he wrote. When asked about the additional information, he explained that his base supporters, agricultural interests, were lined up on the other side.

Agriculture has long had influence in Idaho. But the larger truth today is the heavy hand of the Idaho Freedom Foundation. Republicans like Crabtree cannot afford to buck the IFF too many times or they will face a far-right candidate in the primary. It's likely that today the IFF wields as much power as any single interest in the Idaho Legislature. It has ties to a national consortium of conservative and libertarian think tanks, and the result is look-alike positions to other red states: opposition to teaching social justice in colleges, rallying against governors' stay-at-home orders, favoring public support of private schools while criticizing "government" schools, questioning all-things pandemic, especially masks.

Idaho's political history includes not only Church and Andrus, but also Sen. William Borah, a progressive Republican who served from 1907 until his death in 1940, and Sen. Len Jordan, a Republican who served from 1962-73. Borah preceded Sen. Church as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee. He is remembered as an "intellectual giant" and "truly great man." Idaho's highest peak is named after him, along with many schools and the University of Idaho's annual Borah Symposium on international affairs, and his bronze statue is in National Statuary Hall. Jordan is less celebrated, but his Senate record reveals a progressive spirit. He voted in favor of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the confirmation of Thurgood Marshall to the U.S. Supreme Court and in favor of the Equal Rights Amendment.

The Idaho of Andrus, Church, Jordan and Borah is still a largely rural paradise, but its inhabitants, old and new, have traded self-styled independent conservatives and progressives for hard-right, orthodoxy-spewing politicians. It's a political climate the state's political heroes would not have recognized or appreciated. ♦

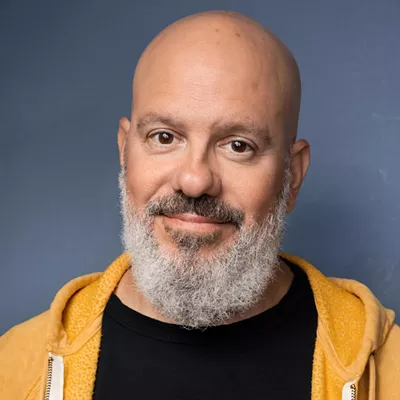

Mindy Cameron is a journalist and author of a memoir, Leaving the Boys, a story of motherhood and career, feminism and romance. A version of this story was first published on postalley.org