Cramped in the backseat on the car drive home from a family trip, Emily checks her Instagram to pass the time. A red dot pops up in the upper right corner of her phone. It's a direct message from someone she doesn't recognize — someone with the handle steven_smith__4.

Emily, then a 15-year-old sophomore at Lewis and Clark High School, thinks it's probably just some creepy boy being weird. She ignores it. When she gets home that night — Memorial Day last year — it's just like any other school night. After dinner with the family, she curls up on the basement couch to finish the last of her homework. But first she takes another look at her Instagram. She finds more messages from steven_smith__4.

Emily doesn't know anyone by that name, but whoever it is seems to know her. He keeps saying she should like him because he's better than the other guys she supposedly likes. She asks who he is. He brings up how she just made the cheerleading team. When she stops responding, he seems to get aggravated, and the messages spiral into something much darker. He calls her a slut and a whore. He sends her porn. He threatens to rape her, explaining in graphic detail — words that can't be printed here — how he'd do it. He says he will shoot up the school.

"I'll shoot up the school with u to go first," he writes, according to court records. "Can't wait till the day that I get to rape u when the least is expected."

Emily, who asked that her last name be withheld so as not to make herself a bigger target, runs upstairs to find her parents. They call 911 and notify a school administrator. The threats toward her and the school appear in the comments of public photos. Hundreds of students see them and in no time they're taking screenshots. Parents text each other and spread the pictures on Facebook. Emily's mom, Callie, tells the other moms not to post the threats with Emily's name. But within hours, seemingly everyone in Emily's world has seen it. Even people on the other side of the country, with little connection to LC, are in the loop.

Yet nobody knows how seriously to take it. After all, nobody took the social media threats seriously from the shooter in Parkland, Florida. Some parents decide to keep their kids out of school the next day. Spokane Police officers try to keep everyone calm as they make plans to post police officers in front of the school the next morning.

This is the state of fear gripping teens across America today. With images of mass school shootings seeped in the national consciousness, social media has provided a platform for school-shooting threats to pop up every day. They appear more often following shootings — Spokane County schools handled more social media threats after the 2017 Freeman High School shooting that killed one boy. Parts of Florida averaged a threat per day in the months after the 2018 Parkland shooting, according to news reports.

Often, the threats target teenage girls or minorities. In September, someone threatened to rape and kill several girls and open fire at students and the school principal at Freedom High School in Oakley, California. In March, schools in Charlottesville, Virginia, closed following anonymous online posts threatening an "ethnic cleansing" at Charlottesville High School.

And as schools go to great lengths to keep students safe and secure, sometimes they can feel more like prisons than places of learning.

"I have teenagers thinking through and thinking aloud, 'If something were to happen here, what is my strategy? What would my actions be?'" says Lewis and Clark Principal Marybeth Smith. "Not thinking of those is not a luxury we have anymore."

For Emily, the vile messages launched what's now been nearly a year of torment. Each time she thinks she can move on, a friend sends another screenshot of an Instagram user threatening to shoot up the school and calling her out by name. She's lost her sense of privacy and control. She's felt anger and frustration as the person allegedly behind it all has so far escaped serious jail time.

But now, she feels empowered, speaking as a girl who has confronted the terror and anxiety triggered by social media.

"We're hiding behind these screens, and all these terrible, nasty things can happen behind it and kids feel like they can't get caught," Emily says. "Social media is just a terrible thing."

The day after the first threats, on Tuesday, May 29, Emily passes by police officers guarding the front door of Lewis and Clark, the largest school in Spokane with 1,800 students. Outside the principal's office, more officers keep an eye out for anything suspicious. Around their wrists, hovering over their guns, they wear #freemanstrong bracelets in recognition of that fatal shooting.

Emily doesn't know what to think. Police have no idea who made the threats. It could be a joke, a hoax, anything. It could be a complete stranger. It could be a boy sitting next to her in class.

"You don't know what could happen, and at the same time, in the back of your head, you want to think it's not real," Emily says.

Emily didn't get an Instagram account until the summer before seventh grade. Most of her classmates already had one, and she felt social pressure to start her own account. She felt obligated to post somewhat regularly. Even the filter she used seemed to matter. The best profiles, she learned, used the same one for each picture.

Still, she enjoyed Instagram more than other social media apps. She learned how toxic social media can be from another app called ASKfm, where kids could anonymously pose deeply personal questions. Sometimes, it was a way to spread rumors and bully each other behind anonymity. It helped Emily learn not to react to what people say on social media. And she learned not to let people know you care.

"It just tears you down more and more, because they get the reaction," Emily says. "It was definitely not something you should be exposed to, because I think it was really degrading to a lot of kids."

But she never experienced the kind of harassment and hate like she received last year.

"Could he go get a gun? Yes. Is his mind in a place that he could do something terrible? Yes."

After that first day back at school, police are still trying to find the person who threatened Emily. She blocked the account, and it temporarily went hidden, but that evening it returns to make more threats to the school. The profile's bio claims there's a "special date planned for LCHS...BE READY...I'm sry ahead of time for those who will not be alive the next day." Spokane Public Schools sends a message to parents saying law enforcement doesn't believe the threats are "credible." Yet there would again be increased security for the next day.

At least 1,000 students — more than half the school — stay home on Wednesday. So does Emily, who has trouble sleeping the whole week.

The Spokane Police Department, meanwhile, obtains search warrants for Facebook and Comcast. They track the IP address to a home on the South Hill, about a five-minute drive from where Emily lives.

It's the home of a boy named Ryan Lee. Emily shares a math class with him. He's a quiet boy, who sometimes offers to help her with homework, she recalls.

Then she realizes this: On that first day back to school after Memorial Day — hours after being threatened with rape and murder on Instagram — she had sat one desk away from the boy allegedly behind it all.

Last year, Instagram unveiled a new tool aimed at limiting bullying and "spreading kindness."

They called it "machine learning technology" that could find bullying in photos and send it to a team to review. The idea was that even if victims of bullying don't report it, Instagram could detect it.

"It will also help us protect our youngest community members since teens experience higher rates of bullying online than others," Instagram said in a press release.

Instagram is popular among teens and typically considered less vitriolic than other social media platforms. But harassment remains a problem among its more than 1 billion monthly users, and even with its new "machine learning technology," it doesn't always shut down harassment when it sees it. It can take days for the company to respond, oftentimes after the damage is done. The Atlantic spoke to one man diagnosed with a form of dwarfism who, as a teen, was constantly harassed, insulted and bullied by trolls. "My entire experience of high school was completely ruined by Instagram harassment," he told the magazine.

Instagram declined to comment for this article when reached by the Inlander.

On Wednesday, May 29, police take in Ryan Lee, then 18, for questioning. After initially denying everything, he admits to creating the account and sending the messages to Emily, court records show. He is charged with felony harassment and communication with a minor for immoral purposes. He spends weeks in a local hospital for mental health treatment before he is booked into jail on June 12; he's then almost immediately released after posting $100,000 bond. On his iPhone and tablet, police are unable to find anything connected to the Instagram account, but investigators do find that the browsing history includes searches of school shootings and serial killer John Wayne Gacy in the days before the threats. They also find searches asking "Can the FBI track Instagram Accounts," from the day he's taken in for questioning, court records say.

The school district and law enforcement tell the media that the threats are not credible because police didn't find weapons in the house, and Lee told investigators that he had no actual plan to carry out the threats. But Callie, Emily's mom, thinks saying it wasn't credible diminished what felt very real to her daughter.

"Could he go get a gun? Yes. Is his mind in a place that he could do something terrible? Yes," Callie says. "When a student makes a direct threat against students or the community, it's credible."

Summer arrives, and Emily tries to get her life back to normal. But even away from school, it's hard. Emily worries she'll see Ryan Lee somewhere, like the grocery store nearby. During Hoopfest, with thousands of people in downtown Spokane, Emily is terrified when she's told that Lee is nearby serving as a court monitor for the basketball tournament. Lee's father is Lewis Lee, who co-founded Lee & Hayes, a firm specializing in intellectual property and internet technology. The elder Lee is also the chair for the Hoopfest Board of Directors.

In August, Ryan Lee is arrested when he violates his terms of release by attending church youth camps, where there are minors and other Lewis and Clark students. (Lee's attorney would not comment for this article. A phone message left for Lee's family was not returned.)

By the fall, Emily is looking forward to a new school year. She has a leadership role as a cheerleader. She is in choir. Everyone at the school is supportive of what she went through.

But in November, Emily is hanging out with her friends on a Saturday night when someone sends her another post using the same handle, steven_smith__4. "Cant wait to carry out what I said last school year," it says, claiming police arrested the wrong guy before. It repeats the same threats as before: Emily would be the first to be shot. Then it would be Emily's friend. "Then I'll follow my list." The account follows other girls' accounts, making some feel like they are on the hit list.

All of the emotions — fear, frustration, anger, embarrassment — come back.

"It seems like I'm exaggerating, but it kind of feels like the world is falling apart," Emily says. "And it's really hard because the second something's out, it's going to spread everywhere, and everyone's going to know."

Smith, the LC principal, says the teachers and staff were angry and heartbroken. They wanted to protect their students. But they also felt powerless.

"We just thought: How did we land here?" Smith says. "How did we land to where this is our reality, where our most vulnerable, innocent, sweet, ridiculous kids are the ones getting threatened?"

Kids often don't know the consequences of their words, and have no intention on following through, says Shawn Jordan, Spokane Public Schools director of secondary schools. At the same time, the district has to take every threat seriously.

"The way we look at it from a threat assessment team perspective is: Does the person pose a threat? Not did the person make a threat," Jordan says. "The things we're looking at are, is there a premeditated plan? Is there a specific target?"

More than three years ago, Spokane Public Schools established a threat assessment team. The district had to do something to respond to a growing concern of social media threats, says Jordan, who's part of the team.

The team as it currently works is based on a model created by John Van Dreal, the director of safety and risk management for the Salem-Keizer School District in Oregon. It includes school directors, counselors, administrators and school resource officer supervisors. In situations involving anonymous social media posts, it will convene and discuss how to communicate with the community, enlist the help of police if necessary, and come up with a plan to assist potential victims.

It's a trending idea in education. A bill that this month has been sent to Gov. Jay Inslee's desk would require each school district to establish such a team.

But it doesn't address the underlying issue of cyberbullying and social media attacks overall. Even Salem-Keizer School District, widely respected for its threat assessment program, doesn't seem to have a good answer for anonymous attacks on Instagram. Just this month, a private Instagram account posted anonymous attacks bullying students at North Salem High School. One post said they wished a student was dead, the Statesman Journal reported.

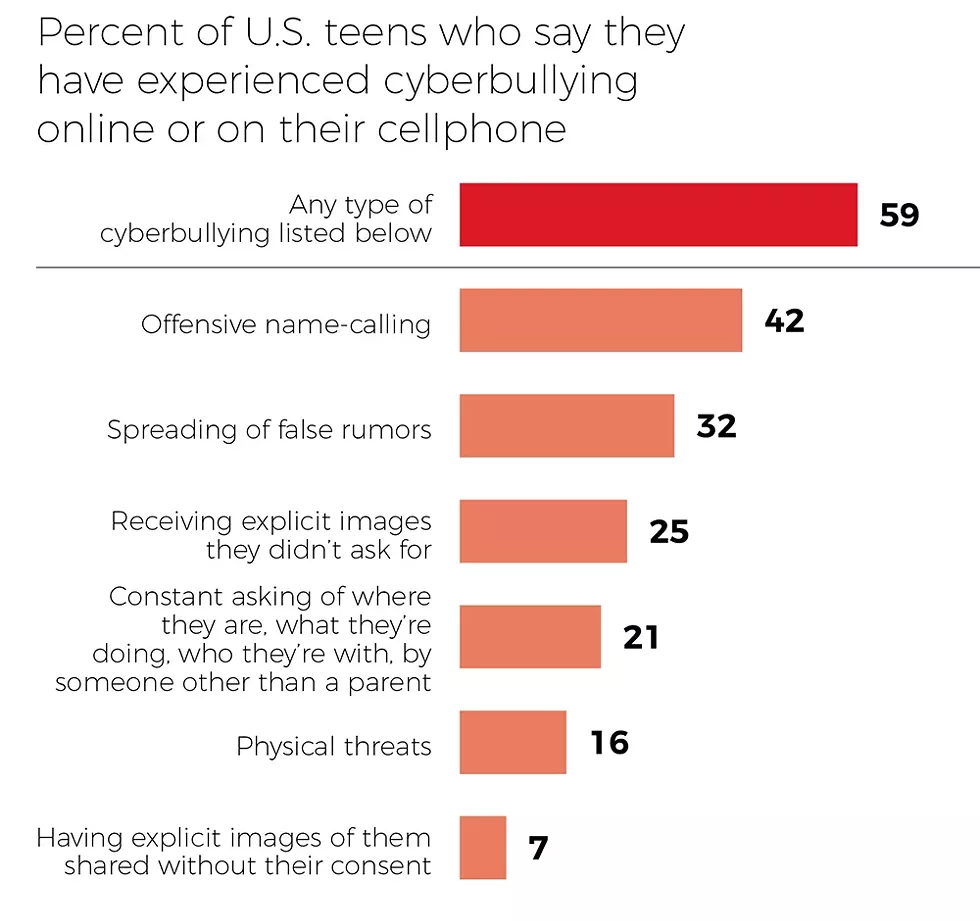

A majority of U.S. teens, nearly 60 percent, say they've experienced cyberbullying in some form, according to a survey done by the Pew Research Center. Name-calling was most common, but one in four teens said they received explicit images they didn't ask for, and 16 percent experienced physical threats. Girls were more likely to receive explicit images and to have false rumors spread about them, according to the survey.

Some schools across the country have begun adopting software that scans student social media accounts to flag threats and attacks. Last fall, the New York Times reported that more than 100 school districts and universities had hired social media monitoring companies in the last five years, including Newtown Public Schools in Connecticut. A federal report on school safety highlighted a Google-funded program in Seattle Public Schools to "identify and negotiate the removal of cyberbullying content," though the district tells the Inlander that program is no longer in use.

Amelia Vance, director of the Education Privacy Project for the Future of Privacy Forum, says the concern with this kind of technology is, well, privacy. Though the technology looks at social media posts that are public, students may not appreciate having "Big Brother" watching their social media interactions. When it comes to identifying threats, having an easily accessible reporting tool that goes straight to the district would be more effective, she says.

"I work with a ton of school districts and they've told me in the wake of every school shooting, they receive an unending list of emails from companies saying, 'We can keep your students safe. We can identify threats for you,'" Vance says. "There hasn't been any real efficacy other than anecdotal evidence."

Spokesman Brian Coddington says Spokane Public Schools is aware of such technology, but the district has concerns about its reliability. Plus, if it's flagging posts 24/7, then the district needs to have someone to respond to it at all hours.

"We're not overly confident that we've found the right solution or that that is the right solution," Coddington says of the technology. "But that is something we've started exploring."

The district monitors social media accounts, mostly just to be aware of "conversations out there," Coddington says. But it's nearly impossible to catch social media threats before students and parents do. And by then, it's too late. Everyone is terrified.

"We're already playing catch up," Coddington says.

Emily misses a whole week of school because of the threats in November. School attendance at Lewis and Clark overall is down that week, but not as much as the first time. Emily hears one student even wore a bulletproof vest to school.

Police aren't able to connect the threats to Lee's IP address this time. But at a certain point, Emily needed to go back to school, says her mom, Callie.

"Parents are in a dilemma because you've got to get your kid back to school," says Callie. "You have to believe everything's going to be OK. But then you feel guilty because you're telling your kids to go to school and what if something happens that day?"

Toward the end of lunchtime on the first day back, Emily is walking with friends to class. Suddenly the sound of alarms pierces through the hallway. She thinks her worst fears are coming true. She rushes to an administrator and asks if she knows what's going on.

"No, I don't," the administrator tells her. "Just get out."

But her fears weren't coming true. The reason for the lockdown was some smoke up on the third floor, says Smith, the principal. Still, the thought that there could be a shooter momentarily shakes the school to its core.

"That was a bad one," Smith says. "People were super angry about that."

In December, a Washington Post analysis found that 4.1 million students endured at least one lockdown in the 2017-18 school year. In Spokane, schools including Lewis and Clark went on lockdown during the shooting at Freeman High School. Yet even as school shootings remain relatively rare, it's the terror created by constant threats and lockdowns in schools that weighs on kids, says Scott Poland, a psychology professor at Nova Southeastern University in Florida.

"The bottom line, and the message that is lost, is that schools remain the safest place that kids go."

And that doesn't even count the lockdown drills to plan for an active shooter, which schools are increasingly trying to make more realistic. In Washington state, schools are required to do three fire drills and six crisis drills per year, which could include an evacuation or lockdown. Sometimes, administrators in Spokane Public Schools won't tell staff or students when it's a drill to make it more realistic, says Jordan, the district's director of secondary curriculum.

Other schools are more extreme. In March, teachers in Indiana were brought into a room and shot with plastic pellets execution style to replicate an active-shooter situation.

"We're going a little over the top," Poland says. "The bottom line, and the message that is lost, is that schools remain the safest place that kids go."

High schools in Spokane have taken other security measures. Students now can only enter the school through the front door. Classrooms remain locked during class. But further measures can be controversial: Arming resource officers could help in the case of a school shooting, but student advocacy groups have pushed instead for more mental health counselors. In Parkland, a school security consulting company called Safe Havens International advised against Broward County Public Schools using metal detectors, but some parents objected. (Safe Havens, meanwhile, is currently conducting a safety audit of Spokane Public Schools.)

Emily appreciates the efforts to keep school safe. She was escorted to class the week after the November threats. During lockdown drills, they make sure she's in a comfortable place. But it can also make her feel singled out and isolated, and that can be worse than the fear sometimes.

"She just wants to be able to go to school and be a normal kid," Callie says.

And every time it looks like she can move on, the nightmare repeats itself.

On Jan. 21, Ryan Lee activates his own Instagram account. In the bio, he writes "no words can describe the public humiliation and trauma I have been put through for the heinous acts of which I was falsely accused of doing." It's a slap in the face, Emily says. She can't believe he would complain about public humiliation.

Then, less than a week later, someone sends Emily another post.

"Mom," Emily said. "There's more."

It is another threat from an account called dan__theman_n. And there's a photo of Emily and her friend, with an X drawn over them saying "put a bullet between their heads." There are more sexually explicit messages. There's a picture of an assault rifle on an American flag. And this time, the threats extend to Emily's entire family.

The repeated threats have been "corrosive" to Lewis and Clark, says Smith, the principal. Students feel fatigued. The fear is the same as the first time, she says. It's just more normal now.

The public posts are reported to Instagram for a threat of violence. Instagram says they do not violate their community guidelines, but that "reports like yours are an important part of making Instagram a safe and welcoming place for everyone."

Back in hallways of her school, Emily passes by students who no doubt know what's been happening to her. She wonders if the other students and parents believed it when she was called the nasty things that were said.

Lately, she's become more withdrawn. She goes for drives on her own, maybe just to a park. Her grades have suffered. Looking for ways to take back control of her life, she wrote a song on the piano about her experience.

"I'm just trying to find my escapes," she says.

Police trace IP addresses from the Instagram account in the latest threats back to the Lee house, records state. Again, Ryan Lee is arrested. Bail is initially set at $1 million, but his defense attorney is able to successfully lower the bail to $100,000.

Again, Lee is bailed out of jail.

Emily's not sure what should happen to Lee, who's now 19 and charged with harassment, cyberstalking and a violation of a no-contact order in connection with the January threats. Court records show that Lee's parents don't believe Ryan did any of it and that it's not consistent with his character, despite his early confession last year. A trial date has been scheduled for June.

Emily still has some sympathy for him, and mostly she wants him to get help. But she feels relieved every time he goes to jail, and anxious whenever he's released.

While most kids are out with friends on weekends having fun, Emily stays home where it's safe, Callie says. She worries about the long-term effects on her daughter.

"The emotional toll that it's taken on her is really hard to watch as a parent," Callie says. "It's a hopeless, helpless feeling."

Emily is not looking for sympathy. She knows all she can do is learn from this, and grow, and try to help other girls in this situation, she says.

But it's changed her. In 10 years, Emily doesn't think she'll remember all the good things about high school. It won't be cheerleading, being on drill team, or socializing with friends that stands out most.

"If I think of high school," Emily says, "this will be all I think about."

On a recent Monday afternoon, the thick wooden doors at Lewis and Clark High School slam behind Emily as she leaves for the day. She's done with school before everyone else, since she opted to take an online class in place of sixth period. She steps outside, but then she realizes she needs to get back in.

"Do you have your pass?" asks a woman over an intercom. She forgot it. Emily has to convince the woman that she is, in fact, a student. Reluctantly, Emily is let back in. ♦

TIMELINE

- May 28, 2018: steven_smith__4 sends a series of Instagram threats targeting a student named Emily and Lewis and Clark High School.

- May 29: Emily goes to school and sits in math class with Ryan Lee, later identified by police as the source of threats.

- May 30: Police track the Instagram account to the home of Ryan Lee, who later that day confesses, according to court records.

- Aug. 3: Arrest warrant issued for Lee for violating release conditions.

- Nov. 3: An account named steven_smith__4 threatens to shoot Emily and her friends at Lewis and Clark.

- Jan. 21, 2019: Emily sees a bio from Lee's personal Instagram complaining of humiliation and trauma he has suffered.

- Jan. 27: Account called dan__theman_n sends explicit messages to Emily and posts threats targeting her and her friends and family.

- Jan. 30: Lee is arrested in connection with latest threats and later posts bond.

- March 8: Lee arrested a third time after violating release conditions.

- March 12: Lee is released on bond again.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Since joining the Inlander staff in 2016, Wilson Criscione has written about an array of issues facing youth today, including youth homelessness, student sexual abuse and childhood trauma during the opioid epidemic. He can be reached at 325-0634 ext. 282 or via email at wilsonc@inlander.com.