Sometimes, timing is everything.

Spokane's Police Guild has gone over three years without a new contract. Since 2017, the city and the Guild have been locked in behind-the-scenes negotiations over pay scales, benefits, and police oversight. Even after an ordinance passed this November requiring union negotiations to be held in public, neither side was willing to say what proposals were being offered behind closed doors.

The public could only wait for an official draft of a proposal to be released.

On Friday, they got one. But the proposed new contract, argues City Council President Breean Beggs, ultimately represents a step backward for police oversight, one that he believes could create a chilling effect on the police ombudsman in charge of ensuring police accountability.

One proposed change, he says, would allow the Guild to try to remove a police ombudsman or a member of the volunteer ombudsman commission for "exceeding their authority."

City Administrator Wes Crago argues that the ombudsman has been "strengthened" overall.

But on Monday, Spokane's current police ombudsman, Bart Logue, sent an email to Crago, the City Council and the mayor ringing many of the same alarm bells as Beggs, warning that "this potential contract greatly infringes upon the independence" of his office.

That loss, he writes, would be devastating.

The City Council plans to vote on the contract next week. It would have been a tough sell for the council to approve at any time.

And what does it say, Logue says, if Spokane can't get real reform done now, with all this national demand for change?

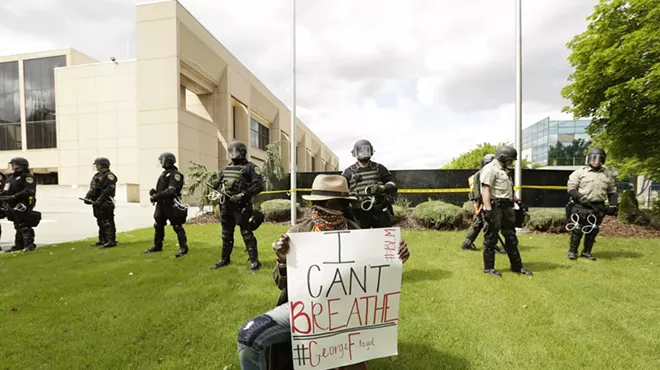

And underneath there's a familiar list of victims killed by police, including New York City's Eric Garner and Sean Bell, Louisville, Kentucky's Breonna Taylor, and Ferguson, Missouri's Michael Brown. But the first name the protester wrote — "Otto Zehm" — was the death that forever altered policing in Spokane.

Almost immediately, however, the ombudsman's office was defanged by a state arbitrator, who declared a significant portion of ombudsman's powers to be an "unfair labor practice."

Even after 70 percent of Spokane voters supported an ordinance in February of 2013 to etch the ombudsman's right to conduct independent investigations into city law, that power has remained at the mercy of the Police Guild's contract.

"Right now, the Guild’s stance is that we can only investigate things that the police department won’t," Logue says. "That’s them dictating what we can look at."

Even his limited ability to write non-binding reports about the police department's actions would be weakened if this passes, Logue argues. He wouldn't be able to declare that an officer's actions broke the SPD policies. He wouldn't be able to cite specific citizens' complaints when he recommends changes for the department.

Sure, Beggs and Logue say that the proposed new contract contains some improvements. The ombudsman would be guaranteed more access to evidence. He'd be able to investigate minor complaints. Most of his powers are expanded to his assistants in the ombudsman office as well.

But all that modest progress, Beggs and Logue say, is washed away by the proposal to give the Guild the power to try to get the ombudsman — or a member of the ombudsman's commission overseeing him — fired for either leaking confidential information or "exceeding their authority." The union would be able to file a grievance and send the issue to arbitration to enforce the agreement.

The proposed contract doesn't outline what exactly "exceeding their authority" means. But Beggs is worried that simply the threat of losing their job could cause the ombudsman to play it safe — and not challenge the police department when it should be challenged.

Similarly, the proposed contract requires all appointed members of the ombudsman commission to have a reputation for "even-handedness," and allows the union to file a grievance to try to prevent candidates who they feel don't from joining the commission.

The Spokane Police Guild did not respond to a request from comment Friday.

She proposed placing a term limit on the ombudsman and lamented that the conflict over the ombudsman's powers may have been hampering negotiations over the police contract.

The closed-door union negotiations mean that we don't know precisely how Woodward's philosophy has influenced the proposed contract.

Coddington says that the city's attorneys concluded that the contract didn't clash with the city's charter and that the provision allowing the Guild to try to remove the ombudsman isn't all that unusual.

Coddington reels off a lengthy list of ways that the city has reformed its police department since the death of Otto Zehm, including adding body cameras, reducing use-of-force incidents, and implementing crisis-intervention training.

The proposed contract, he says, involved compromises made long before the current national conversation about police brutality.

"It still does not comply with the charter of the city of Spokane with regard to an independent ombudsman. I’m disappointed if they’re not there yet," Cathcart says. "Seven years after the charter amendment was approved — 14-15 years after the tragedy that was Otto Zehm."

Cathcart says he wishes he could separate the financial piece from the oversight piece — granting the police department their long-overdue raises without approving the limitations on the ombudsman.

"These people in blue have been waiting so long for the next chapter of their lives," Wilkerson says. "[But] that ombudsman thing that has dogged us forever. The community needs reconciliation on that."

The community needs transparency and accountability from the police department, she says, to provide healing and build trust.

The protests, she says, have opened the floodgates of decades of locked-up frustration from older black Americans. She recalls the "How Long? Not Long" speech that Martin Luther King, Jr. gave on the capitol steps in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965.

But says she's not tipping her hand for how she's going to vote on the contract.

Beggs hits a similar theme. He still believes the same things he did when he was an attorney fighting for police reform — but he knows that he's now representing both the cops and those who are marching and calling for defunding them.

"Whether you're the person who got a knee on their neck or you're the person doing it in the middle of the riot, they're all people," Beggs says. "We have to not demonize each other."

Even if the council approves the negotiated contract, it will expire at the end of the year.

Negotiations on the next contract will likely start this fall. As the outcry reaches a volume that's rarely ever been seen in Spokane, Beggs says simply punting on the police oversight questions until the next contract has become a lot more difficult because of the protests.

Yet both he and Logue see that as an opportunity for real reform.

"We’ll never have as many sympathetic ears as we will in this moment," Logue says.