The tweet, from an account called "Yes, You're Racist," captures the moment in freeze frame: A young man grinning in the glow of white supremacists holding tiki torches. "This is James Allsup — speaker at the alt-right rally, [Washington State University] College Republicans president," the tweet announces.

And while Allsup's planned speech is canceled, his own streaming video footage makes clear his allegiances in last month's clashes in Charlottesville, Virginia: When white nationalist Richard Spencer — who has called for a "peaceful ethnic cleansing" — appears before cheering onlookers, Allsup runs up to Spencer and thanks him.

Within moments of students and administrators learning of Allsup's involvement in the rally, where a Nazi sympathizer drove into a crowd of protesters, killing a woman, they demand action. WSU President Kirk Schulz takes to Twitter after the "Yes, You're Racist" tweet to issue a statement condemning racism, Nazism and the violence in Charlottesville.

"I was heartbroken," Schulz says in a letter to the campus. "Hate has no place at WSU."

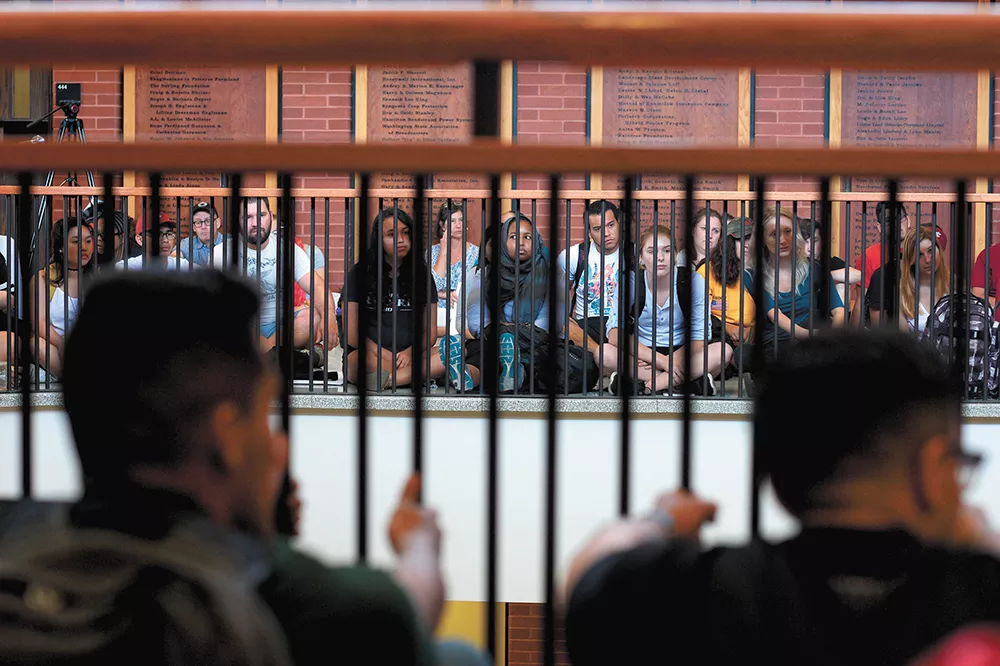

It isn't nearly enough to mollify critics. Students and alumni condemn Schulz's statement as weak and equivocal, and nearly 6,000 people sign an internet petition insisting that WSU "must expel James Allsup for Nazi activities." Allsup's resignation from the College Republicans doesn't end the firestorm. Students organize a "March Against White Supremacy" on Aug. 19. Two days later, a bomb threat and Nazi graffiti force the evacuation of a dorm. The following week, hundreds of students hold a sit-in protest inside an administration building and deliver a list of demands.

"I worry about the campus being painted with any particular brush," Schulz tells the Inlander. "We had [only] one person attend the Charlottesville rally."

Yet a group of 12 Democratic state lawmakers still called on Schulz to strip official recognition of the WSU College Republicans, so students could "see that the University is truly not tolerating and encouraging hate speech."

Welcome to the new culture wars gripping colleges across the country. One side accuses the campus of complicity in racism, and calls for restrictions on students' free speech rights. The other mocks these students as overly sensitive "snowflakes" and delights in stoking their anger.

The situation is hyper-charged by a social media landscape that can inspire and outrage student activists, or simply exhaust them. It can allow figures like Allsup to hitch himself to a national movement and become a social media star in the process, or it can crush students under the weight of an online mob. And it may foreshadow where the country, in the age of Twitter and Donald Trump, is headed, as small but vocal groups of white nationalists clash with the demands of multiculturalism.

"The atmosphere on campus continues to worsen as tensions thicken," says Chijioke Emeka, president of WSU's Black Student Union, who helped to organize the Aug. 25 sit-in.

'INTENDED TO CAUSE PAIN'

"Less tweets!" somebody shouts.

And in response, the crowd of over 200 students packed into a WSU administration building thunders: "More action!"

They chant that "white silence is white violence" and that the "people united will never be divided."

The protesters, driven by a coalition of five different minority student groups, are demanding change. "We sit in," students proclaim on a big sheet of butcher paper, "till WSU stands up."

"We argue that any institution where any student feels not only comfortable, but also safe enough, to spew hate and encourage violence says a lot about this climate and environment," says Emeka in a statement about the sit-in.

During the last few years, a movement at U.S. colleges has sought to eliminate offensive ideas from campuses. The college campus, many students feel, should be a "safe space" protected from words or ideas making students feel uncomfortable.

To some on the left, words can be violence. Something as seemingly innocuous as asking "where are you from?" could be considered what's now known as a "microaggression," a common interaction felt as a slight or insult against marginalized groups. And students often blame school officials for allowing hateful words to be expressed at all. At times, it's bordered on the absurd: Students at Oberlin College in Ohio, for instance, lambasted inauthentic cafeteria sushi as "cultural appropriation."

But Emeka says her classmates aren't reacting to a single incident. Instead, they see a troubling pattern.

"It has been one incident after another here at Washington State University, and the responses from the administration, or lack thereof, are unacceptable," Emeka says.

For starters, there was the Trump wall. College Republicans, led by Allsup, built it last October: an 8-foot-high wall, surrounded by red caution tape, with "TRUMP" written on the faux-brick surface with big white letters. About a dozen Trump-supporting students were dwarfed by more than a hundred counter-protesters. A number of undocumented students attend WSU, and to the counter-protesters, the wall represented an enthusiastic celebration of a candidate's policy calling for them to be deported.

"I feel as though I shouldn't have to worry about going to class and being faced with something like the Trump wall, and dealing with the fact that like, 'Oh crap, there's James Allsup, he's right there,'" says Nicklaus McHendry, a WSU student who helped organize the sit-in.

To that, add a slew of anonymous racist messages that have popped up on campus in the past year. First, the N-word was found etched in the library above the words "Trump 2016." Later, in November, a student's car was painted with anti-gay slurs. Then, in February, fliers popped up on campus claiming in bold capital letters that "IT IS YOUR CIVIC DUTY TO REPORT ANY AND ALL ILLEGAL ALIENS" to immigration enforcement.

"Using the Trump momentum and energy, I've been able to connect with hundreds, millions of people across the country who share similar beliefs." — former WSU College Republican President James Allsup

Then, in May, in the middle of finals, a pseudonymous troll named "Ultramemelord" uploaded a video: Someone had added racist commentary over footage, taped by Allsup, of an argument at the Trump wall between a white student in a Trump hat and several black students. The edited version of the video adds text saying, "Maybe you should go back to Africa," and includes a clip of a child with an accent saying, "I do not associate with n———."

In a statement titled "No place for racism at WSU," Schulz says the video was "intended to cause pain to our community of color at WSU." In a tweet, he promises the university "will hold the person who did the video accountable." But anonymous internet videos can be just as hard to track down as anonymous racist graffiti. The culprit is never found.

That's a fundamental difference that the social media age has brought, says Mary Jo Gonzales, WSU's vice president of student affairs. Decades ago, a racist idea would have manifested as a poster on campus. Now, it can be broadcast for hundreds of thousands of people.

"Social media has forever changed the vitriol of the conversation," Gonzales says.

By the time students organize the sit-in protest, shortly after the start of the new school year, their frustration is palpable. (The authorities would later arrest and charge Jose Andres Tecuatl, saying that the resident advisor who'd reported the bomb threats and swastikas to the campus police was allegedly behind them.)

"In the first week of class, we shouldn't have to deal with three swastikas and two bomb threats," Emeka says during the sit-in, according to the Spokesman-Review.

They're tired of official statements and initiatives and committees and task forces — they want actual change. So they lay out their demands: Mandate cultural competency training programs for staff and students. Hire more people of color. Protect the multicultural centers and Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies courses. Build more "gender-inclusive" facilities — that can be used by any student, no matter their gender — and offer free menstrual products in all bathrooms.

And, most controversially, they call for the university to separate "free speech" from "hate speech."

McHendry says what the right is being asked to do is not drastic.

"They're being asked to not be racist, and they're being asked to not be homophobic, and they're being asked to not be transphobic," McHendry says. "And that's a threat to someone who has never experienced actual discrimination."

THE KIDS ARE ALT-RIGHT

A Trump bobblehead stands on the bookshelf behind James Allsup. A Trump poster, "Hillary for Prison" and "Infowars.com" stickers decorate his computer. Two Cathy McMorris Rodgers stickers are stuffed in the bottom of his trash can. He threw them away sometime after the congresswoman for Eastern Washington disavowed his involvement in Charlottesville.

Allsup, surrounded by sound equipment, studies notes for a podcast he's about to record.

"I just always think it's funny that from here, a room in a townhouse, we're able to produce content for YouTube and stuff that, like, beats KXLY," Allsup says.

Allsup's influence at WSU is undeniable — even if others, like President Schulz, downplay the influence of a single person in a student body of 30,000. Allsup has driven right-wing activism on campus, where it was previously nearly nonexistent. And he's served as a catalyst for resistance from the left.

David McLerran, the president of the libertarian Young Americans for Liberty club on campus, says Allsup has unquestionably been the most influential figure on campus, socially and politically. He's taken advantage of the political climate. As a result, McLerran says, the campus has become more divided — the right has gone further right, and the left further left.

Allsup has nearly 18,000 Twitter followers, more than twice as many as Schulz. He has 150,000 YouTube subscribers, 55 times more than WSU's official college YouTube channel. Using only the internet and social media, Allsup has built a dedicated national following.

Allsup helped to increase enrollment in WSU College Republicans from only a few members to around 40, he says. Allsup's successor as College Republican president, Amir Rezamand, says he's proud of what the club has done over the last year. He calls the Trump wall a "big success" and notes Allsup's "unique" way of doing things.

On a recent Saturday morning, from his bedroom studio setup, Allsup messages the co-host of his Nationalist Review podcast, 19-year-old Nick Fuentes, a former Boston University student who left the school after he says he received death threats for his political views. A woman once secretly recorded Fuentes saying race-mixing was "degenerate," and before the podcast starts, Allsup laughs at sound bites he plays of the woman talking about Allsup and Fuentes.

"These people just take themselves so seriously," Allsup says.

Allsup hates being labeled a racist, a Nazi, a white supremacist, even a white nationalist. The media got it wrong about Charlottesville, he says. Just because some people carried Nazi flags doesn't mean everyone there is a Nazi, he says. It wasn't him carrying a Nazi flag. It wasn't him shouting the N-word.

Allsup's beliefs have evolved. As a teenager, he says he was into anarcho-capitalism, a philosophy calling for the elimination of the state in favor of private property and a free market. He supported Ron Paul when he ran for president in 2012.

After he became WSU College Republican president, Donald Trump changed everything.

"He's given me a career," Allsup says. "Using the Trump momentum and energy, I've been able to connect with hundreds, millions of people across the country who share similar beliefs and similar concerns about the future of the country."

He describes himself as a nationalist. He wants all illegal immigrants, and all recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, out of the country. That includes DACA students at WSU.

Allsup dismisses the word "racist" altogether.

"It's a racial preference," he says. "But 'racist'? Like, I don't think the term 'racist' is even a real term. I think 'racist' is only used to try to attack people on the political right most of the time."

The answer echoes, nearly word-for-word, what Richard Spencer, the white nationalist, told Allsup once in an interview. Allsup says he prefers simply "nationalism" because that way he doesn't need to get caught up in a "purity spiral" and the intricacies of "what percent white" it would need to be.

He fears living in a society where whites are a minority.

"I don't want to be a minority," he says. "Being a minority sucks. I think that's an area where I can agree with people on the left."

Yet he doesn't think that minorities in America are disadvantaged. White politicians, he says, are not advocating for white interests in the way they should, he argues.

When discussing the issue with Fuentes, they eventually agree that races should not be forced to associate with one another. Fuentes calls it "peaceful segregation." Allsup prefers "freedom of association." They lament that not enough research has been done to study the IQ of different races and scoff at the idea that "anthropological research" could be racist.

"We live in such a bubble of discourse that we can't talk about those things," Allsup says. "But in the media, if you were to bring it up, it would be this horrible racist conspiracy."

Of course, there are places where talking about that kind of stuff is celebrated. All across the internet, for one.

Conservative pundit Ben Shapiro says social media can provide the mix of anonymity and community that can allow alt-right beliefs to flourish. He should know: He was formerly an editor-at-large at Breitbart News, yet found himself the main target of anti-Semitic tweets during the 2016 campaign.

"If you go around to your local group, and say, 'OK, how many people believe that white people are superior?' How many hands go up in that group of 100? Zero?," Shapiro tells the Inlander.

But on websites like Reddit, he says, there are entire anonymous communities where everybody believes white people are superior and are eager to talk about it.

Shapiro points to a progression: A young conservative starts out enjoying, say, the politically incorrect memes, like jokes about the shooting of the gorilla Harambe, on anonymous messageboard websites like 4chan. But then they start to glom onto other taboo stuff, like discussions of racial IQ.

"I think the gateway drug is sort of fun and troll-y stuff," Shapiro says. "I don't think it always mainstreams into actual alt-right white-supremacist ideology, but it can."

According to a tweet in May, Allsup has been marinating in 4chan since he was 12 or 13 — starting at a board called "/b/" focused on internet memes and randomness and eventually ending up at "/pol/," the "politically incorrect" message board brimming with fringe beliefs and racist jokes.

In her book Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars From 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and Alt-Right, author Angela Nagle lays out two opposite camps online: On the one side, there's the flourishing identity politics of left-wing communities on sites like Tumblr and Salon, where a "culture of fragility and victimhood" is mixed "with a vicious culture of group attacks" against anyone who says anything insensitive. On the other, there's the anarchic raunch at anonymous cesspools like 4chan, reveling in obscene and racist provocations.

"The hysterical liberal call-out produced a breeding ground for an online backlash of irreverent mockery and anti-PC," Nagle writes.

"I'm not even convinced he believes half of what he says, to be honest. I think he's just the living, breathing, walking version of a meme." — David McLerran, president of libertarian Young Americans for Liberty club at WSU

McLerran, the president of the libertarian Young Americans for Liberty club on campus, calls Allsup a "provocateur," and suggests he was born out of internet culture.

"He wants to be offensive. He wants to get under people's skin," McLerran says. "I'm not even convinced he believes half of what he says, to be honest. I think he's just the living, breathing, walking version of a meme."

Allsup is constantly recording his interactions with the left on campus and posting them on YouTube. When Trump won the election, he approached Trump protesters on campus and asked if they were excited. When the protesters drowned him out, shouting "F—- Donald Trump," Allsup yelled, "White man, yeah! I love being a white man."

The YouTube video, titled "Students TRIGGERED by Trump's victory," got more than a million views. It's an intentional dig at the term "trigger warning," a statement that precedes material that could be distressing to a victim of trauma.

Allsup denies he's only seeking a reaction. Instead, he says he's trying to challenge others' ideas, though that doesn't stop him from posting their reactions online for fun.

"That's how this genre works," he says.

So while Shapiro is glad to see campus conservatives become more willing to take the fight to the left, he says there are a few who respond to the left's identity politics with white identity politics. And then each side attacks the other, feeding each other, ramping up the aggressiveness.

"It's reaction to reaction to reaction to reaction," Shapiro says. "It's a cycle of reaction."

FREE SPEECH ISN'T FREE

WSU's David Leonard, a professor in the department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies, got his Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley, the liberal institution where, in the '60s, students led the Free Speech Movement, fighting to overturn a ban on political activities on campus.

But Leonard, who writes about the intersection of white supremacy and culture, says the context around free speech is different these days.

"Often those who are advancing 'free speech' today, that has more to do with levels of prejudice, than the principle of free speech," Leonard says. "The principle of free speech has become a vehicle to justify and rationalize."

Indeed, left-leaning student activists at Berkeley are now seeking restrictions on free speech, particularly against controversial speakers at universities. When Shapiro spoke at Berkeley this month, the campus paid an estimated $600,000 to law enforcement for security, though Shapiro blames outside anarchists more than students.

A Gallup poll last year found a large majority of college students supported schools being able to police intentionally offensive language and restrict costumes that stereotype ethnic groups. Washington state institutions are no exceptions. At Western Washington University, students crashed a trustee meeting last year, demanding the university create a student-led committee with the power to terminate professors for offensive speech.

Last spring, Evergreen State College professor Bret Weinstein questioned an event that asked white students to leave campus for a day, and the resulting protests became so intense that police told Weinstein it wasn't safe for him to be on campus. ("F—- free speech," one Evergreen student told VICE News as other students snapped their fingers in agreement.)

"We are witnessing the sabotage of the core principle of a free society — rationalized as self-defense," Weinstein wrote on Twitter after resigning from the university and receiving a $500,000 settlement. "Short term, it's a big win for the right — most especially the reactionary fringe."

In a meeting with college officials after the sit-in, WSU protest organizers lamented how free speech had been "misinterpreted" and that current college policies had "loopholes" that have allowed hate speech to proliferate on campus.

The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that the Constitution gives public institutions little power to crack down on offensive speech, except in very narrow circumstances like explicit threats, repeated harassment or obscenity.

But Leonard pushes back against those who would dismiss student complaints about microaggressions, noting research that shows campus climate can impact a student's education. Lately, that climate has been exhausting for many students, and not just because of what's happening on campus, he says.

Before smartphone video, many agonizing police shootings would have gone largely unseen. Before Twitter, many outrageous comments would have gone unread. Today, it's hard not to feel it all as a deluge. Leonard notes an instance when a student was contacted by a white supremacist because of something they'd written on their class blog. In another case, a WSU student who objected to the racist video on Twitter found herself singled out by alt-right websites.

"Our political climate in our country is becoming more fractured. We see a microcosm of our national political feelings played out on our campus." — WSU President Kirk Schulz

Ari Cohn with the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, a national nonprofit focused on civil liberties on college campuses, says that social media can exacerbate free speech fights on campus by elevating controversial student comments. It doesn't help, he adds, when some students seek intentional provocation.

"Making a free speech point by simply saying the most outrageous thing you possibly can? It's not helpful," Cohn says. "It makes actual free speech advocates' lives more difficult."

On top of that, the pressures of social media can cause college administrators to overreact as they try to deal with the public outrage that can result.

"They know that one viral tweet could be the end of the career," Cohn says.

Schulz knows those pressures well. He says he often finds out about the latest controversies through Twitter. A decade ago, with the rise of Facebook as the primary social media site, administrators had time to wait to put out a statement.

"We could put out something on Monday and everyone went, 'Oh, the university is being responsive,'" Schulz says. "Now, if it's out on social media it's seen as — 'Well, it's out there. How come you haven't done anything?'"

At WSU, a week after the sit-in, some student leaders held a "free speech" rally in response to the demands from other student groups to regulate "hate speech."

WSU student Andrew Luedeke, state director for Young Americans for Liberty, believes free speech shouldn't be curtailed. But he understands why some students, feeling targeted by Trump and Allsup, want restrictions.

"There wouldn't be a call for a reduction of free speech on campus if it wasn't for people like James Allsup," Luedeke says. "He has definitely sparked a debate about what should be allowed to be said on campus."

So far, Schulz has largely resisted the calls for campus censorship. In response to the Democratic lawmakers calling on him to boot the College Republicans, he cited the $5 million that WSU spends annually to create a diverse, supportive campus culture, but declined to punish the College Republicans.

He adds that organizers of the sit-in, after discussing the constitutional limitations of a public university, have shifted their goals — focusing more on clarifying the university's harassment and disruption policy to address student conduct.

"We allow our students to say what's on their mind," Schulz says.

MENDING THE TEAR

Sitting on the stage after hosting a town hall two weeks ago, Schulz expresses a bit of optimism.

"Our political climate in our country is becoming more fractured," Schulz says. "We see a microcosm of our national political feelings played out on our campus."

But the meetings with the sit-in organizers have been productive, he says. What started as student demands have turned into requests, he says, though he knows that students won't be satisfied until they see real changes. In June, the university announced a new campus climate initiative. It includes hiring a new administrator to coordinate campus culture activities and appointing an external review team to look at the university's diversity efforts.

"Our students are willing to give us a chance to sit down and work with them. I don't see that everywhere," Schulz says. "I think that says a lot about our student body."

Among some students, there's an eagerness to have more civil political discussions. This year, WSU senior Stella Kim and several other students formed the Political Science club at WSU to bridge the divide on campus, calling for a "stronger focus on having civil political discussion."

Political groups across the spectrum at WSU have seen their membership levels explode — and the numbers haven't declined after the election. Gavin Pielow, president of the WSU Young Democrats, looks at campus debates between Republicans and Democrats — and side-by-side columns in the student newspaper — as a positive trend.

"We've way too often become unwilling to compromise," Pielow says. "Perhaps the political climate has been poisoned by the isolation. We're unwilling to hear another side out."

But Allsup sees another development: politics at WSU and across the nation are being redefined. It's identity politics, with both sides using race and social background to infuse their ideology, he says. And he sees that as a good thing.

"I think Donald Trump radicalized American politics and I think Trump was the catalyst for these emotions and feelings," Allsup says.

Allsup is the extension of that at WSU. But if it weren't Allsup, McLerran thinks it would have been someone else.

"WSU is a reflection of the times," McLerran says. "I don't think the times are a reflection of him." ♦

Forrest Holt contributed reporting to this story.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story has been updated to correct Dr. David Leonard's academic department at WSU

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

DANIEL WALTERS covers Spokane City Hall, business and development for the Inlander. Since 2008, Walters has followed house-flippers sniffing out foreclosures during the recession, dug into the mess that dogged the vacant Ridpath Hotel for nearly a decade, and explored the dramatic economic disparity between the swanky Kendall Yards and the low-income West Central neighborhood that borders it. He currently rents a one-bedroom apartment in Browne's Addition. Reach him at danielw@inlander.com or 509-325-0634 ext. 263.

WILSON CRISCIONE, born and raised in Spokane, is an Inlander staff writer who covers education and county government. His work previously appeared in publications including the Spokesman-Review, and before joining the Inlander in 2016 he wrote about education and crime for the Bellingham Herald. Contact him at wilsonc@inlander.com or 509-3205-0634 ext. 282.