What is a book?

To most people, the answer is straightforward: a collection of writing, bound between two covers, perhaps.

Beginning with clay tablets and then moving to papyrus scrolls, the book's form has constantly been modified to adapt to an ever-changing reader demographic.

But to a niche subset of artists, the book is loaded with infinite complexities.

Hollow out the pages of a hefty book to store your prized possessions in, and you've made a piece of art called a faux book. Fold a piece of paper into a mini magazine, and you've created a zine, one of the most common forms of book art.

These artists challenge a book's purpose by deconstructing, reimagining and redefining what exactly a book can be.

Book art communities have long been thriving in big cities like New York and San Francisco, both boasting their own museums specifically for book art and adjacent works. Seattle is home to multiple book art groups, maker circles, book art collections and book art societies. Portland is no different.

Book art has yet to have a big moment under the Inland Northwest's often-present sun. Some artists are convinced that time is drawing nearer, however, as book art bubbles toward the top of the local arts scene of late.

But just like a book's myriad possible contents, pinpointing exactly what book art is can be difficult, and widely varies from artist to artist. Here, you'll meet three book art fanatics in the greater Spokane art community who hold a deep love for the art form and aim to spread the good word of book art to as many people as possible.

MEL ANTUNA HEWITT

Full-time Spokane bookbinder and book artist

Some books get shipped out from Amazon warehouses, collect dust on bookshelves and under beds, or sit at 0 percent complete on an e-reader. Other books are laboriously stitched together by hand, bound and illustrated by one singular artist.

Bookbinder and book artist Mel Antuna Hewitt is self-taught and motivated, and aspires to bring book arts into the spotlight in Spokane with her hand-stitched journals and artists' books.

Hewitt has two great loves in life: making things and reading.

"My fondest memories are from when we would visit my tante [aunt] in Germany," says Hewitt, also known in arts circles as Mel the Maker.

"She always had this book of arts and crafts for kids, 'basteln' in German, and I just loved it," she continues. "One year we made a lantern out of paper with a candle in it. That always stuck with me because it was something that I made that was beautiful and also useful. That was the first piece of the puzzle."

The second piece appeared to Hewitt during college, where she was studying theater.

"My roommate, who was in graduate school, started taking a bookbinding class," she says. "And I was like 'What? You can take classes for that kind of stuff?' But I was deterred because she told me that the classes usually fill up fairly quickly. Looking back, that was really stupid of me to not even try."

After college, Hewitt got married and had two children. After the birth of her second child in 2015, one of the happiest moments in her life quickly turned into months of postpartum depression and anxiety. In order to deal with the overwhelming feelings she was experiencing, Hewitt turned to her love for the power of words.

"At the time I was on a really big journaling kick," Hewitt says. "It was one of the best ways for me to process everything that was going on in my head. So, I thought that I could start by making my own journal and filling it with my thoughts."

Hewitt sought out every bit of information she could find about bookbinding. She scoured YouTube, read every book she could get her hands on, and came out of the experience with newfound knowledge and a handmade Coptic stitch (a flexible chain stitch used for bookbinding that was originally developed in the second century) journal with exposed binding.

From there, Hewitt's obsession with the craft snowballed. She began making more journals, as well as leather-bound books for family members, and started to see her love of books as a form of artistic expression.

Hewitt's artists' books often stay true to the traditional book form.

"One of my very basic definitions of a book is that it must hold knowledge," she says. "Book arts is a huge umbrella term that encapsulates fine binding, conservation, repair and sculptural book objects. It covers all of those areas."

One of Hewitt's first artists' books is titled Be Healed. The small rectangular book is skewered by an orange prescription pill bottle. Once the bottle is removed from a circular hole, the book can be thumbed through, read, and the bottle can be also opened.

During a February event for Spark Central's Creative Circle series, Hewitt describes this artists' book as another way that she dealt with her postpartum depression.

"In the Bible," she explained at the lecture, "there is a woman who is cured of a long-lasting ailment because she touched the cloak of Jesus. When in the thick of my suffering, I wished that I could touch that cloak and be healed from everything I was feeling."

Inside the prescription pill bottle Hewitt placed a piece of white cloth that reads "be healed," a nod to the mental health journey she went on after the birth of her daughter and a tangible object serving as a reminder of her healing process.

Hewitt's other artists' books deal with moments of personal and global significance. Many of these were created during the 2020 pandemic lockdown and the tumultuous political atmosphere during that period.

Honey was created in response to an @AreYouBookEnough Instagram prompt based on the word "hexagon." When Hewitt began formulating the idea for her hexagonal piece, bees came to the front of her mind.

"I came across the thought that within their hexagons, bees store honey which is their livelihood and all they need for sustenance," she writes in an Instagram post.

The resulting creation is a fully formed hexagon constructed out of paper and thread. The pages inside of the hexagon create an intricate pattern. These pages cannot be flipped through like a traditional book but have words written on them in yellow ink. Peer in closely and the three-dimensional pages reveal Hewitt's "honey," the things she needs for sustenance.

"Spouse," reads one of the pages. "Love," reads another.

Is Honey a book?

By some definitions, yes. It contains pages, text and some semblance of binding. Technically, Honey conveys information about Hewitt's life, but the form of Honey is so nontraditional that no reader would ever pick it up for a casual flip-through.

BOOK ARTS VOCAB LIST

Altered Book

An art object that has been created from an existing, printed book.

Artists' Book

Not an "artist's book," not an "art book." An artists' book is a work of art that utilizes the form of the book and is made by an artist.

Book Arts

Art taking the form of or made from a book.

Democratic Multiples

Typically inexpensive artists' books sold cheaply or even given away to as many people as possible.

Editions

When an artist works in editions, they create multiple of the same, or similar, books for purchase or display.

Endbands

A part of a book, most often found with hardcover bindings, that consists of a small cord or strip of material affixed near the spine to provide structural reinforcement and sometimes a decorative effect.

Endpaper

A blank or decorated leaf of paper at the beginning or end of a book, usually fixed to the inside of the cover.

One-of-a-Kinds

When an artist works in one-of-a-kinds, they create only one of each book. These books are usually not similar to other books the artist has made.

Text Block

All of the leaves in a book on which the text is written or printed.

Zine

A small-circulation, self-published work of original or appropriated texts and images, usually reproduced using a copy machine.

But that's what makes Hewitt's book art creations so special: the blurring of the lines between the worlds of fine art and literature.

"For a long, long time there were very few people who were still practicing making books by hand," Hewitt says. "If we want to be able to keep this art form, then we need to make sure that people can experience this unique joy of having handmade books available to them."

Hewitt is doing everything in her power to bring that joy to Spokane.

In early 2022, Hewitt and local hobbyist bookbinder Beth McIlraith created the Inland Northwest Book Arts Society in hopes of drumming up support and chatter about the local book arts community. So far, the group has five regular participants.

"There's a huge part of me that wants Spokane to understand, appreciate and acknowledge books as art," Hewitt says. "There are plenty of groups over on the west side like the Puget Sound Book Artists and such, so if we want to commune with other book artists, we would have to drive four and a half hours just to do that. My dream is to have that same accessibility over here."

While Hewitt says her own life is in flux right now, and that she doesn't know where she'll be in five years — let alone the state of book arts in Spokane — she hopes the region expands opportunities to explore book arts.

"My hope is that we have an accessible collection here," she says. "I would love to see more book arts classes being taught in the universities. Book art is so important to the art world, but also just to life in general because it teaches us that things don't always just have to be one certain way. Books can be a lot of different things if you open your mind."

AMANDA CLARK

Dean of the Library & Special Programs at Whitworth University, book art enthusiast

There's love for what you do, and there's doing what you love. Amanda Clark is doing what she loves.

A self-proclaimed book art enthusiast and book art scholar, Clark serves as dean of the Library and Special Programs at Whitworth University, overseeing the school's collection of rare books, including a small collection of artists' books.

"When I was getting into this field about a decade ago, it was just starting to get popular," Clark says. "And nowadays, you go to Terrain and there's a piece of book art on the wall. It's everywhere."

Thanks to Clark, Whitworth's Cheney Cowles Library houses a mishmash of book art.

An excavated book sits in a glass case near the circulation desk. Its cover and pages have been sliced with an Exacto knife, allowing only certain illustrations and words to come to the forefront. A student-made altered book piece hangs on the wall near employee offices. Pages of various books have been shaped into miniature playground equipment, the tiny words barely legible. Students pass by, and some spare an extra glance, but most stroll past on their way to a study session or class.

Clark graduated in 2013 from the University of Alabama with a Ph.D. in library science, a degree equipping future librarians with the knowledge of how to organize and manage books, as well as other information through collecting and preservation. She added some flair to her studies by combining her affinities for books and art.

"I didn't want to hate what I studied by the end of my program," she says. "Alabama has a great book arts program, so I decided to incorporate that into my studies. Many people in the field are obsessed with democratic multiples [artists' books produced in large quantities], so I decided to take the alternate route and study one-of-a-kind artists' books."

Clark says scholars typically avoid studying these unique artists' books because it's troublesome, expensive and hard to acquire solid information without reaching out to the artists directly. During her postgraduate research on the subject, Clark found herself back in the Pacific Northwest asking artists to allow her to see and photograph such works.

After completing her 400-page thesis on one-of-a-kind artists' books, she'd acquired dozens of new connections to book artists in the Inland Northwest.

One point of contention within the book arts community is what exactly constitutes a work of book art. Some artists are pickier than others, claiming the piece must have a spine, pages, text or other bookish elements. Others, like Clark, are less concerned with specifics and more concerned with the discussion that ensues because of the art.

"It's healthy to untangle definitions," Clark says. "I like to keep very broad definitions of what book art is. Like my necklace, it's a little microfilm of a magazine. It doesn't have words, but it communicates something. So, I think it's definitely a piece of book art."

She believes anything that conveys a feeling or communicates information can be considered book art.

The Whitworth library's special collections include artists' books from prolific local creators like Hewitt and Colfax-based Timothy Ely alongside work from Tacoma artist Jessica Spring.

Spring's book Trump and Judy is a play on the English puppet duo Punch and Judy. It features four sets of pages each containing rhyming couplets accompanied by an illustration. A pull-down tab on each page reveals a Donald Trump quote that slides down to cover the main illustration.

"Trump hammers on women, minorities too. Only rich white men's causes does he give due," reads one page. The pull tab then reveals the quote, in red ink: "There has to be some form of punishment," as well as the context of the quote, "Trump on women seeking abortion, 2016."

Clark stresses the importance of keeping artists' books like Spring's accessible to the public.

"Over time, artists' books become more and more like historical documents," says Clark. "They pinpoint specific moments in our history and must be preserved just like any other historical document."

TIMOTHY ELY

Colfax-based bookbinder

Upon entering Timothy Ely's home studio, it's apparent that you've been transported to an alternate universe: a space full of geometric shapes, archaic machines, unfamiliar objects and, of course, a world where books reign supreme.

There's no need for interstellar travel — the entirety of this sci-fi setting sits just a couple of stories above downtown Colfax.

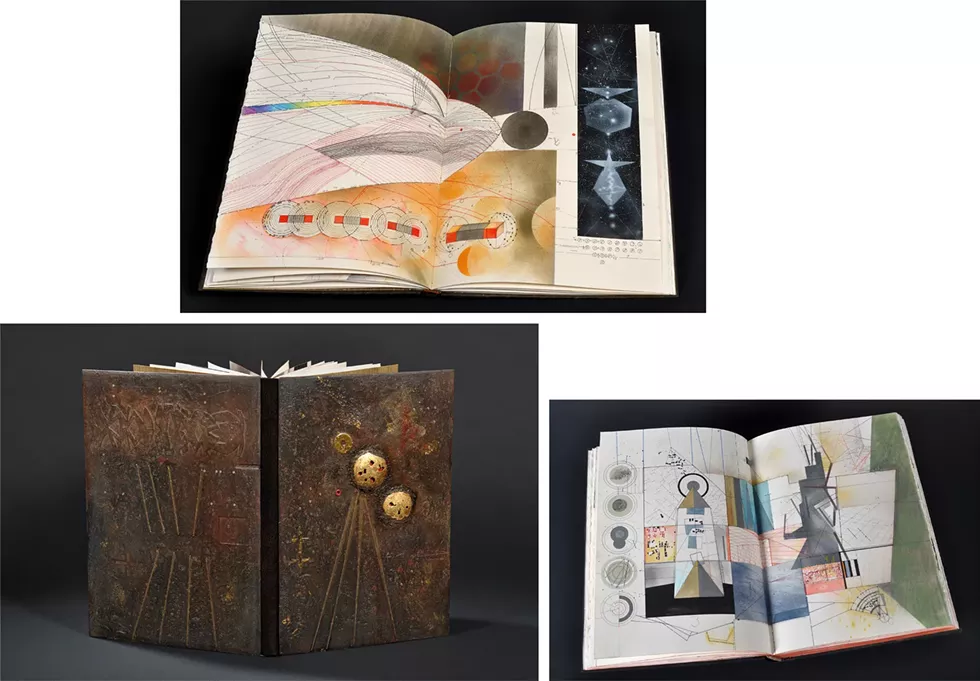

Like his studio, Ely creates drawings that can only be described as otherworldly. Pages are strewn about, littering various countertops and drawing desks. The paper itself is carefully crowded with vaguely space-like objects, diagrams and glyphs that Ely calls "cribriform."

Upon first look, the drawings make no sense. But, that's exactly what Ely hopes for.

"I've always been really interested in how libraries catalog things," he says. "I don't want my books to be easily categorized. So, a lot of my stuff depicts maps, diagrams, things that deliver information, but then I want to squirrel it around and make it something that's abstract."

One of Ely's books, Obelisk Stare, reflects this notion to a T.

The cover is textured, rough to the touch and looks like rusted metal that's been out in the elements for years. Open it up, and be greeted by stark white paper with gray and red geometric forms sketched with precision across the page. Though these patterns look as if they could resemble something that exists in our plane of existence, the longer you look, the more jumbled the shapes become.

Look even longer, and you might be able to decipher the story they tell.

Ely's fascination with abstract art started, unsurprisingly, with a book, an atlas he was gifted for graduation.

"I went to a local public library on the west side and noticed that they had all of these atlases, but in different languages," Ely says. "I was viewing a landscape from above, but I couldn't read it. I was intrigued by that. It gave me the scale that I work in now."

October 22, 1975. That is the exact date that Timothy Ely first decided to use books as a means of artistic expression.

"Oh, also that was around 4:15 pm," he says with complete seriousness.

In the 1970s, there was little information out there about how to craft a book of your own. Let alone in the tiny town of Snohomish, where Ely hails from.

"The only bookbinder I found at that time lived in Seattle, and he was really cranky," Ely says. "He was just not willing to help me at all because he figured I would become a binder and try to compete with him. But that's not what I was about. I couldn't even tell him what I was about because I had no clue yet."

During this research period, Ely saw his first artists' books in the University of Washington special collections library — handmade, manuscript books, and plenty of them.

"They were just beautiful," he says. "It was transformative."

Ely went from one bookbinder to another, seeking out information on how to bind his own books. One finally gave him a chunk of bookbinding leather and sent him on his way, not knowing that would be the catalyst for Ely's entire career.

Ely is what the book arts community calls a "one-of-a-kind" artist, meaning he makes only one copy of each of his artists' books. However, his process is even more intriguing due to the fact that he not only creates the art, but also binds and presses books himself, a lengthy process that not many do without help from outsourced companies or experts.

LOCAL BOOK ART EVENTS

The following events are hosted at the Spokane Print & Publishing Center at 1921 N. Ash St. To register, visit spokaneprint.org

Book Arts: Secret Belgian Binding with Mel Antuna Hewitt, April 20

Paper Marbling with Mel Antuna Hewitt, May 18

Typesetting with Thom Caraway, May 20

Japanese Stab Stitch Binding with Bethany Taylor, May 27

Lego Printed Zine with Mel Antuna Hewitt, June 22

It's been almost 50 years since Ely began making his artist books but, much like tomes throughout history, his have also morphed in form over the years.

"At first, it was like falling into a wealth of knowledge," he says. "Nothing has been subtracted from my process, just a lot of things have been added. New tools, lots of new processes, new people, new ideas. Lots of reading material. Books feed books."

Ely uses his art to capture the unknown, the unthinkable. Just like his art, he has a hard time defining his role in the greater book art space. He's not fond of the title "book artist" or even "artist." Even so, Ely believes everyone involved in the book-making process is something of a book artist, from the calligrapher to the binder, the paper-maker, and even the writer.

"Book arts is a very accessible thing in my eyes," Ely says. "You know, you can buy the ingredients to make cookies, and you're a baker. You can also get a needle, some thread and leather, and make something. Then you're a book artist."

Even in Colfax, a rural town of just 3,000 people, there might be others who also consider themselves book artists. But there is only one Timothy Ely.

"Art is something that happens between a person and an object," he says. "So if someone views a book as art, then it is."

Books are bought and borrowed. People take them home, read them in bed, on a park bench. As long as there aren't any world-scale apocalyptic events or Fahrenheit 451 situations, books will continue to exist and readers will continue to consume them.

On the other hand, artists' books like Ely's don't get around much. People don't view artists' books in the bathtub or bring them to the waiting room of a doctor's office. But artists' books are loved, preserved and cared for, usually more so than ordinary books.

So what exactly is a book? Is a book a piece of art?

There are infinite answers to those questions. You, dear reader, must decide for yourself. ♦