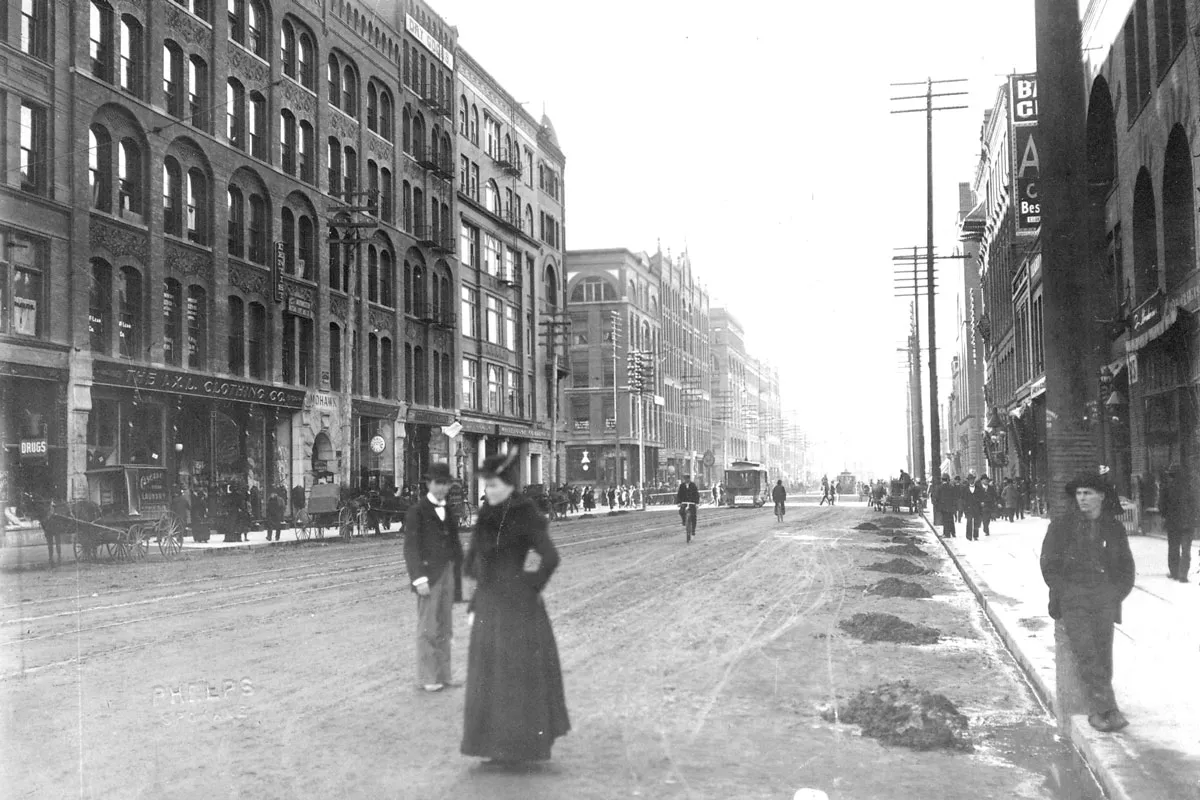

Though it may be hard to imagine today, Spokane was once a hotbed of labor radicalism. And for a month — November of 1909 — all eyes of the nation were trained on the city for outlawing speaking in public. Hundreds of men and women who came to the city to challenge the seemingly un-American policy were thrown in jail.

Well before 1909, the West had ceased being the land of opportunity advertised in railroad circulars; the fertile farmland and hillsides filled with gold had long since been locked up by big business. The thousands of immigrants, then, were left to working whatever wages were available. Thus the tension between labor and capital — a tension as old as the idea of private ownership — came out West.

In the early 1890s, there were individual unions representing specialized industries. But it became more and more clear to union leaders that the workers willing to work for the lowest wages not only had a natural, common bond but were also in need of a union more than any profession.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was hatched in Chicago at a 1905 founding convention. Later, the members became universally known as Wobblies. The chairman of that convention was William D. Haywood, known as Big Bill; he was also a key figure in the Western Federation of Miners. Two years after the formation of the Wobblies, Haywood was accused of hiring an assassin to kill former Idaho Gov. Frank Steunenberg, who had been murdered at his Caldwell, Idaho, home in late 1905. Haywood was defended by Clarence Darrow and acquitted in a widely publicized Boise trial. The whole episode — from the labor unrest in the Coeur d'Alene mining district that started it all to socialist radicals on the streets of New York City — was retold in the book Big Trouble by Anthony Lukas.

The first sentence of the Wobblies' constitution gives a glimpse into the union's attitude: "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common." And by 1912, the Wobblies had created such an impression that the New York Times stated that: "Since Camille Desmoulins climbed on that table in Palais Royal in 1789 and unloosed the French Revolution there has been no movement about which it behooved conservative citizens to be more thoughtful." This statement came despite the fact that the Wobblies advocated nonviolent means to achieve their goals. They also stood out from other unions for allowing Blacks and Asians into their ranks.

It's hard today to transport yourself back, to understand how radical labor advocacy could have such an appeal. But consider: It was still before the bloody Communist revolution in Russia; the United States had just come through the Gilded Age, in which the rich had gotten much richer and the poor had struggled to keep their heads above water. Socialist ideas were accepted by hundreds of thousands of Americans as the antidote to such a state of capitalism run amok.

* * *

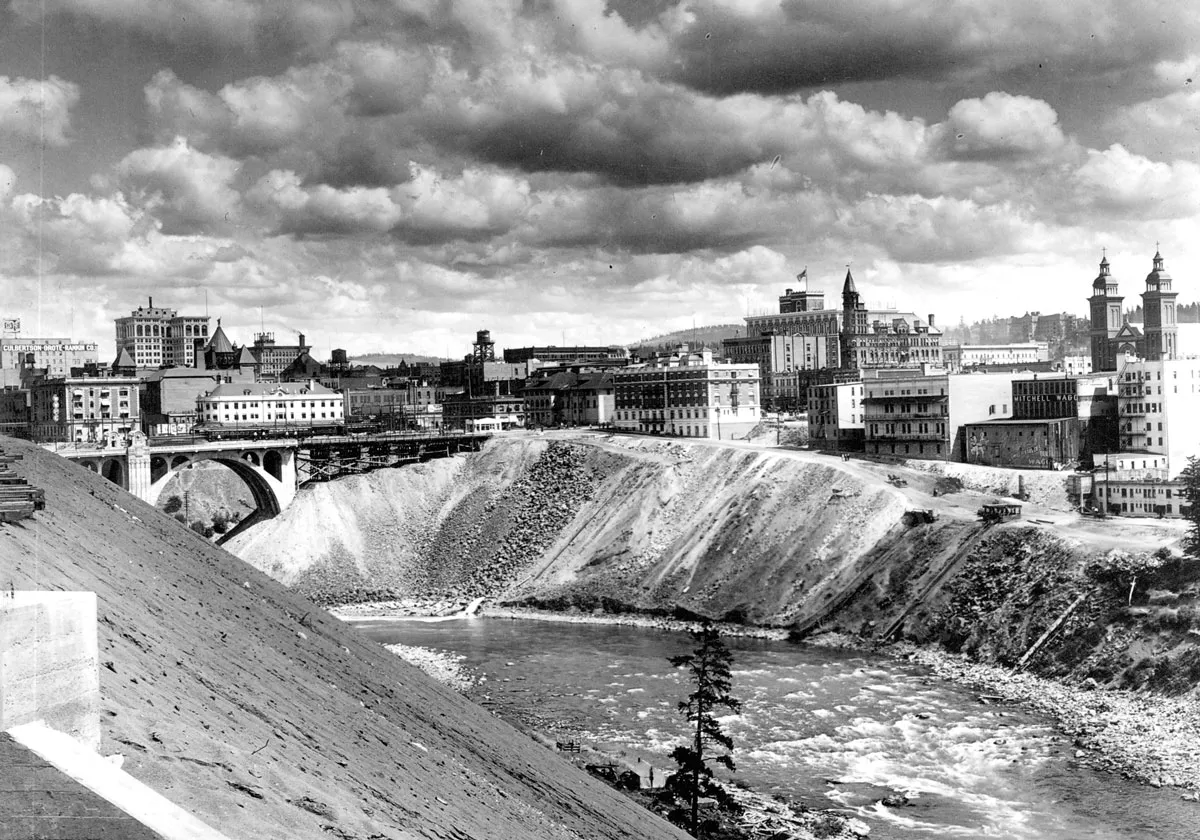

By 1908, Spokane was especially suited to become the site of the Wobblies coming-out party. Its location, central to many labor-intensive operations, made it a gathering place for wage-workers. In Spokane, you could find work in the mines of North Idaho, the orchards of Wenatchee or the pine forests of northeastern Washington. But, as you can imagine with a population of rootless workers, the chance for fraud was high — and workers were taken advantage of by "job sharks," as they were called.

The Wobblies managed to gain a foothold in Spokane, with its first large membership of nearly 3,000. And their first act was to go after those employment agencies, who they accused of exploiting workers by charging them for finding jobs that either weren't there or didn't pay what was advertised. It's even possible these agencies were working in collusion with the employers.

While the Wobblies went about attracting new members on the streets of Spokane, the job sharks weren't going to give up the fight for their livelihood — corrupt or not. On Dec. 22, 1908, the owners of the employment agencies pressured the Spokane City Council to make it against the law "for any person ... to do any act which shall tend to draw a crowd." Though clearly unconstitutional under the First Amendment free speech provision, the law was not without local precedence. From as far back as 1891, Spokane's municipal code claimed it was unlawful to "do anything ... upon the sidewalks which shall have a tendency to frighten horses, or which shall collect any crowd so as to interfere..."

But with the older ordinance, enforcement was lax; the new law was written to be enforced. This point was driven home in March 1909, when the City Council amended the December ordinance to exempt religious organizations. In short, Wobblies were being singled out to be banned from the street corners they had been speaking from to find recruits and warn workers against the sharks.

* * *

Two people also came into the orbit of the Wobblies by 1908 — people who would add to the spectacle that was about to be created by the two forces colliding. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was a black-haired, 19-year-old Irish firebrand of a public speaker from New York City. She began her labor advocacy at age 15, preaching socialism to crowds on the sidewalks of Brooklyn. For her precocious talents, she was tagged by the author/journalist Theodore Dreiser as the "East Side Joan of Arc."

By 1909, she was working full time for the Wobblies as a speaker and agitator. In the summer of that year, she became the resident speaker at Spokane's IWW Hall; in the fall, she and her husband were sent to Missoula to recruit for the IWW. It was in Missoula where free speech tactics were first used in any major way by the Wobblies. The union had recalled Flynn to Spokane in November, where she put those tactics into well-publicized motion.

After her first Spokane conviction, she stated her motivation for being a labor radical: "All my life I have seen my family and my class suffering under the inequalities of the system that makes multimillionaires at one extreme and toiling slaves at the other. I am in it because I want to see those who produce the world's wealth get better wages and shorter hours." She continued: "This is my first trip to the 'Wild and Wooly' West, but I have failed to see the much-wanted independence and democracy."

Another occasional socialist speaker was Fred H. Moore, a Spokane attorney. He had lived in Spokane since 1901 and was admitted to the bar in 1906 at the age of 23. The IWW retained him in 1908 as their chief legal representative in Spokane.

In the weeks leading up to November, Wobblies were called into Spokane from throughout the West and Midwest to challenge the city's policy. The Spokane Police Department prepared, and the citizens of Spokane were left to follow the unfolding story through their three newspapers: The Spokane Press being the most sympathetic to the cause of labor; the Spokane Daily Chronicle being the mainstream afternoon journal; and the Spokesman-Review as the voice-of-the-establishment morning paper, whose owner William H. Cowles often railed against the vice that characterized early Spokane.

To re-create that month here, we have scoured those three newspapers for firsthand accounts of what happened. Readers should then keep in mind that these are reports of the day. Accounts given from either side may well be tainted by their desire to win the battle for good publicity along with the free speech issue. We have tried to follow events that were reported in all three, using actual headlines to illustrate the news of the day.

MONDAY, NOV. 1, 1909

"7,000 IWW MEN HERE FOR BATTLE," proclaims the Spokane Press banner headline. ... Acting Chief of Police John T. Sullivan issues the following order to all officers: "In anticipation of trouble because of threats made by the Industrial Workers of the World to speak on the streets in defiance of the authorities, I will ask all members of the police department to report at this office tomorrow, November 2, 1909, at 12:30 pm, fully equipped and in readiness for duty if the occasion requires it." The chief also promises reporters that the Wobblies will be treated humanely, but "we will not kill them with kindness." ... A special rock pile is reserved for the Wobblies at Monroe and Broadway.

TUESDAY, NOV. 2

"Police keep down riot mobs; station 2 to 6 police on about every corner." ... The IWW fulfills its promise and takes to the streets to violate whatever ordinance might be in effect. ... The presiding judge quickly agrees with Fred H. Moore's argument that Spokane's latest ordinance against free speech on street corners is unconstitutional. But he's just as quick to suggest to the police that speakers could just as easily be charged under the city's broad disorderly conduct ordinance. The street speaking ordinance remains on the books, but Wobblies are now arrested for other crimes. ... Much of the action takes place in the vicinity of Stevens and Front (now Spokane Falls Boulevard). ... Socialist leaders in Everett, Yakima, Seattle, Portland, Los Angeles and Chicago are telegraphed: "Big free speech on in Spokane. Come yourself and if possible bring the boys with you." ... Local Socialists and club women come to the support of the Wobblies in announcing a "Free Speech" mass meeting at the Masonic Temple for the next night. ... IWW leaders and the editor of The Industrial Worker are arrested at their headquarters. ... A total of 103 street speakers are taken into custody.

WEDNESDAY, NOV. 3

"More than l50 prisoners, mostly enthusiasts, confirmed in jail on charge of disorderly conduct and street speaking." ... Each prisoner, according to plan, demands a separate trial. ... Attorney Moore receives the following wire from IWW headquarters in Chicago: "Use habeus corpus with all arrests. Call governor's attention to state of Colorado's paying $10,000 damages in like actions. We are in this fight to the finish. Instruct any deported persons to return to Spokane at all hazards. Immense defense fund being raised, publicity being given." ... Moore announces that Judge C.E.S. Wood, Portland anarchist and legendary Indian fighter, has been engaged as counsel to assist him in defense of the prisoners. ... Prisoners refuse to go on rock pile and are placed on a diet of bread and water.

THURSDAY, NOV. 4

IWW officials threaten to sue the city over conditions in the city jail, where as many as 24 prisoners are crammed into a 6-foot-by-8-foot cell. Many become sick and faint, but an open window is denied them. ... A bulletin is posted at IWW headquarters stating that last night, Teamsters' Local 202 of the AF of L adopted this resolution: "We will stick by the IWW in its fight for free speech until hell freezes over." ... Fire hoses are turned on street speakers and some listeners.

FRIDAY, NOV. 5

Wobblies tell the press that, "We do not ask for the privilege of holding meetings on Riverside. We are sure we cannot get recruits to our ranks from the Silver Grill nor Davenport's. We want to work down here among the employment offices where there are wage-earners." ... The IWW posts the following bulletin: "The IWW and the police have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as the police use clubs and hose, and the IWW uses the pen and tongue."

SATURDAY, NOV. 6

"The IWW cases moved along easily and smoothly. 'William Lofholm,' shouted the bailiff. Lofholm took the stand. 'Making a speech?' inquired the magistrate. 'Yes. sir,' came the reply. 'Thirty days,' said the justice." ... Prisoners go on hunger strike. ... Edith Frenett gives the Spokane Press an account of her ordeal in jail: "Arrested on Tuesday at 2 o'clock, in two hours we were covered with vermin, denied the use of soap and towels, prevented from seeing counsel, jeered by the officers as though we were monkeys in a cage. During the first night, the steam heat was first turned up to a suffocating degree and then turned completely off causing the cell to turn ice cold." She had been released on Friday afternoon. ... The editor of The Industrial Worker gives a statement from his cell to the Spokane Press, which sympathized with the Wobblies' cause: "I asked to see the warrant for my arrest, but they refused to show me one. One of the men present said that I would see 'the rope' before I saw a warrant." As for conditions in the jail, Wilson said: "Most of the time there were from 20 to 28 men in the cell. The floor was slippery with vomit. One man who had an ague chill from a malaria attack, and who vomited all afternoon, asked the doctor for medicine. This man was from a malarial district of California, and the doctor simply told him there was no malaria in Spokane, and added, 'If you were not all anarchists, you would not be here, and I will see you in hell before I give you any medicine.'" ... More jail scandal: Agnes Thecla Fair is arrested for speaking. She is questioned by police in a darkened cell. She refuses to answer questions and she alleges that one of the men makes a sexual threat, then another officer begins to unbutton her blouse, sending her into convulsions. She is not able to sleep or eat after this.

SUNDAY, NOV. 7

Socialists hold a free speech fundraising lecture event in Oliver's Hall at 334 W. Riverside; $100 is raised. The meeting closes with the audience singing "Keep the Red Flag Flying, Comrades." ... The night is capped off with a packed house at the IWW Hall where Louis Catewood, "who admitted with evident pride that he had been a member of the Western Federation of Miners during the trouble in the Coeur d'Alene district, harangued the audience for two hours, uttering fiery, profane tirades against the police, press and pulpit."

MONDAY, NOV. 8

Agnes Thecla Fair is ordered released by the prison doctor. "After being released by the judge on her own recognizance, Agnes Fair is paraded by her comrades through the streets to her rooms on a stretcher. She had appeared rather faint as she left the courtroom." ... "There are three demonstrations, bringing 30 arrestees to court. Police turn over records of those arrested who are not citizens to federal authorities."

TUESDAY, NOV. 9

"War Department grants police of Spokane use of guardhouse at Fort George Wright for incarceration of IWW members arrested for street speaking." ... Sometime around this time, city officials decide to use the newly constructed Franklin Elementary School, located on East 17th Avenue, as a makeshift jail.

WEDNESDAY, NOV. 10

A pregnant Elizabeth Gurley Flynn arrives in Spokane from Missoula to "take charge of local forces and edit weekly journal." ... City Council hears arguments against the speaking ordinance. Moore presents a compromise statute based on the ones in Seattle, New York and Chicago. Flynn gives an impassioned plea for the idea, which is supported by the Central Labor Council. The council rejects the proposal.

THURSDAY, NOV. 11

The Spokane Press writes: "The big press associations have taken hold of the agitation, and Spokane is now daily held up to the gaze of the entire country."

FRIDAY, NOV. 12

"STARVATION STRIKE IS OVER; BEG FOR FOOD AND EAT LIKE WILD CREATURES; Prisoners at Fort Wright, Franklin School and Jail Give In." ... A Superior Court judge turns down further writs of habeus corpus on the grounds that they are only wanted to "raise Cain."

SATURDAY, NOV. 13

Streets are quiet ... IWW prisoners bathed by "being put through streams of water as fast as jailers can put them there."

SUNDAY, NOV. 14

Denied the use of a private hall, the Wobblies are given the use of a city courtroom for a public meeting. Flynn speaks: "It is not often that the IWW is permitted to speak in this temple of injustice. If the police and city government refuse the Constitutional right of free speech, the working man should refuse to work, and if the working man refused to work there would not be a single fat capitalist eating turtle soup in Davenport's tonight."

MONDAY, NOV. 15

At a meeting of about 500, held under the auspices of the Socialist Party, a resolution was passed to boycott the National Apple Show, now about to open in Spokane. ... Rumors fly that Clarence Darrow may join Moore in defending the Wobblies. One of Darrow's associates is already bound for Spokane from Chicago.

TUESDAY, NOV. 16

Fred H. Moore proclaims the Goddess of Justice to be dead in Spokane. ... Wobblies announce they will flood the city with lawsuits for false arrest and imprisonment.

WEDNESDAY, NOV. 17

An employment shark at 31 S. Stevens loses his license for illegally selling a job. ... Wobbly John Poss demands that he be allowed to return to jail and suffer with "the boys."

THURSDAY, NOV. 18

Flynn leaves Spokane for a few days to address the Butte Miners Union. ... Wobbly George Smith announces an intention to sue the city over a beating the police gave him at the station. ... Judge Mann declares in passing on one of his street speaking cases: "I may not be right. I may be wrong, but until the higher court decides otherwise, I will continue to rule in these cases as I have been doing."

FRIDAY, NOV. 19

More Wobblies from Montana and California are on the way. ... The editors of The Industrial Worker, after spending two weeks in jail, finally get their day in court.

SATURDAY, NOV. 20

"At a conservative estimate, the IWW agitation has cost the city $100 a day," said Chief of Police Sullivan. "In this estimate I include the expense of extra officers, food and fuel. There will be no letup as far as we are concerned," continued the chief. "We have not only plenty of room but plenty of bread and water."

SUNDAY, NOV. 21

Edith Frenette is arrested for the third time, this time for singing "Red Flag" from the porch of a residence near the Franklin School, then on the outskirts of town. After hearing her recite the lyrics in court, the judge sentences Frenette to 30 days. ... Flynn addresses the meeting in Butte, charging that Spokane policemen look and act like "a herd of gorillas," and may even be what "Darwin could not find." She claims that Spokane judges have no minds to make up and says she fears some prisoners may not get out of jail alive.

MONDAY, NOV. 22

Wobblies point to the death of a union member trying to get to Spokane as the first casualty of the free speech fight. The 23-year-old was killed in Wisconsin, under a train he was hitching a ride to Spokane on.

TUESDAY, NOV. 23

Fred H. Moore puts out the word that the great socialist Eugene Debs has been ordered to abandon his trip to California to come to Spokane. ... Wobbly S. Sorenson is arrested. When he gets to jail, a policeman informs him that he is to be thrown in the Spokane River. He is put in a sweatbox, the size of which was 6-by-8 feet. Then, in his words, "They left me and six fellow workers in there for 17 hours with the steam turned on, then they took us out and put us in an ice-cold cell... We were tried in bunches of eight and 10 before Judge Mann who was so drunk that he was almost unable to keep his seat." (Sorenson made this report to the U.S. Industrial Relations Commission in 1912, when the commission was collecting reports on free speech fights like Spokane's.)

WEDNESDAY, NOV. 24

Chief Sullivan threatens to arrest Eugene Debs if the famous socialist tries to speak on the street. Sullivan brags, "I am no respecter of persons in this case. I wish the newspapers would call these people by their right name. They are anarchists, pure and simple, and their song of the Red Flag is one of the most inflammatory things I have ever heard."

THURSDAY, NOV. 25

Chief Sullivan announces that IWW prisoners will get only bread and water this Thanksgiving Day. Those Wobblies out of jail vow to also go on a starvation diet of bread and water in sympathy with their comrades.

FRIDAY, NOV. 26

"Refusing to cut or carry in wood for fires to keep themselves warm, members of the Industrial Workers of the World confined at Franklin Schoolhouse last night at eleven o'clock became desperate from the cold and began tearing away the woodwork in the rooms in which they are held prisoner to make a warming blaze."

SATURDAY, NOV. 27

"The chain gang goes out this morning with a membership of 15, all of whom are former street speakers. The chilly weather is bringing the prisoners into submission."

SUNDAY, NOV. 28

"Members of the Industrial Workers of the World confined at the city jail did their best to break up the religious services of the Salvation Army in the jail corridors. All the time the services were going on, the jail rang and echoed with the shouts and noises made by the IWWs in their efforts to drown out the hymns and prayers."

MONDAY, NOV. 29

All remaining criminal conspiracy cases receive a change of venue from Judge Mann at municipal court to Judge Hyde at the courthouse. The grounds are that Judge Mann stated the week before in open court that if he were a practicing attorney he would not defend such cases as those of the IWW. ... More than a score of new Wobblies arrive from Chicago. ... Flynn speaks at the IWW hall, alleging that, "If the gentle carpenter of Nazareth was on earth today he would be fighting for free speech in this city, unless Chief Sullivan had him in jail."

TUESDAY, NOV. 30

Flynn is finally arrested. In her own words: "At about eight o'clock [in the evening] I was walking toward the IWW Hall. As I reached the corner of Stevens and Front I was accosted by officer Bill Shannon with the demand, 'Are you Miss Flynn?' I replied yes. When he grunted, 'Well, we want you.' I asked, 'Have you a warrant?' 'Naw, we haven't,' he rejoined, when the other plainclothes man stepped up and remarked, 'There is one in the station.' I accompanied them to the police station where I was booked and the warrant read for criminal conspiracy. I was then taken to the chief's office, where Prosecuting Attorney Pugh put me through the third degree." During the interrogation, Flynn said: "He asked, 'Did you say so and so in your speeches?' To which I replied, 'I talk so much I don't know what I say.' They all gave him the laugh, and he asked if that statement wouldn't probably, if published, ruin my reputation as a speaker. Anxious he was for me to maintain my status as an agitator, indeed!"

Despite Chief Sullivan's words to the contrary, with expenses mounting, national publicity casting a shadow over the city and jail space running low, the city lost its nerve. In the weeks after Flynn's arrest, the city quietly slowed, then stopped pursuing the street speakers, as if they had made their point after arresting the Wobblies' leader.

But in the aftermath of the month of November 1909, all sides could claim victory in some way. Despite perhaps being judged by history as more a fascist regime than an example of democracy, Spokane ultimately regained control of its street corners and had the peace of mind of knowing it had stood up to an outside threat and survived. And despite having hundreds of its members spend weeks in jail under bogus arrest, the Wobblies not only cemented their national reputation as in-your-face worker advocates, but also saw reforms hit Spokane. In the year following the free speech fight, Spokane wages were raised, matrons were hired to supervise the jails, the city's government structure was scrapped and replaced, the street-speaking policies were moderated and Chief Sullivan and four of his officers were fired. (In 1911, Sullivan was found murdered in his home; no one was ever charged with the crime.) Most importantly, however, the city outlawed the "job shark" agencies that the Wobblies started their protest over.

The Spokane experience gave great hope to the Wobblies, but by 1920, when the Communist Revolution in Russia had painted radical unions as dangerous, it was smashed by federal prosecutions of its leaders. Federal regulations improving working conditions also marginalized the need for such a union. But in the meantime, Wobblies continued free speech fighting, descending on towns where a point was to be made — and they continued to be harassed and even murdered, as happened in Everett in 1916. Later, in 1936, a small group of still active Wobblies was even shot at by hired guns for timber companies in St. Maries, Idaho.

Fred H. Moore moved in 1910 to Los Angeles, where he continued to defend labor activists, including those involved in the Los Angeles Times bombing of 1911 (with Clarence Darrow as co-counsel) and the Everett Massacre case. He also defended the famed Sacco-Vanzetti case from 1920-24, in which many historians believe the anarchists were wrongfully executed for a bombing. Moore died of cancer in Los Angeles in 1933.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was tried and convicted of criminal conspiracy in Spokane on Dec. 6, 1909. Her appeal in February 1910 was more successful, and she was acquitted, perhaps in no small part due to her advanced pregnancy. Flynn left Spokane, had her baby in New York state and went on to become one of America's most notable Communists. She was arrested, along with 12 others, in 1951, and was convicted under the obscure Smith Alien Registration Act of 1940. As a result, she spent more than two years at the federal women's reformatory in West Virginia. Flynn later became chairperson of the American Communist Party; she died in the Soviet Union in 1964, was given a state funeral and is buried in Red Square. ♦

THE COLD MILLIONS

The history of Spokane in the era around 1909 is just too rich not to be brought to life in a novel. And in focusing on the epic drama of the free speech fight led here by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, you can wonder why nobody had done it before. Thank God Jess Walter got to it first. If this taste of Flynn's story, published here, has you thinking, "Wait, that all happened... in Spokane?" then you have to read The Cold Millions.

For anybody, anywhere, this is a ripper of a read. But for those of us who live here — some of us for many years — it's more like magic. Walter has brought this mostly forgotten era to life in a way no "official" city history ever could — or would. I always knew crazy, unprecedented wealth flowed through these streets at that time, but I never heard much about the other side of the Spokane Story in school.

Dropping characters of his own creation — Rye and Gig Dolan, to name two — in the middle of actual events and real people, Walter gives himself the license to roll through a vivid panorama of the way it was around here. And his research is impeccable. Yes, this is a work of fiction, but he nails the details.

There's been a growing pride of place these past two decades. If you've lived here as long as Jess Walter, you've lived through the times when everybody seemed to be moving to Seattle or Portland. The local culture was a pervasive sense of not quite being up to snuff. But now, with every Spokane Doesn't Suck T-shirt proudly worn, you can feel something's changed. We're hungry to know more about who we are and where we came from. The Cold Millions offers an electric new perspective on the foundations of our civic character.

Official Spokane, circa 1909, was proudly on the wrong side of history. Brave, peaceful, relentless protest was needed to bring change, and under the glare of national disdain, Spokane changed its unAmerican ways. And even more change would come. After 1910, when reforms swept local government, then later as Prohibition dawned, Spokane cleaned up its act and settled down. You could say that, like most frontier towns, we grew up and became a lot less of a wild child, and more great-place-to-raise-a-family-ish. You could call it boring, even — more of the kind of place you moved away from, like both Bing Crosby and Kirtland Cutter did. Still, seeds were planted in that tumultuous year.

The Cold Millions offers a beautiful coda for those — like Jess Walter — who stayed through all the years to build this place into something with its own cultural texture, a place to feel connected to and proud of. Even the seemingly a-political, just-keep-working types, if they open their minds to a variety of perspectives and mix with different kinds of people — the way Rye Dolan did — they, too, can carry the fire of justice in their hearts. The echoes of the civil rights movement and Black Lives Matter ring powerfully through Walter's final pages.

Perhaps only a novel can deliver the kind of history that makes you feel a connection to the past. For me, that's part of what makes The Cold Millions The Great Inland Northwestern Novel.

— Ted S. McGregor Jr.

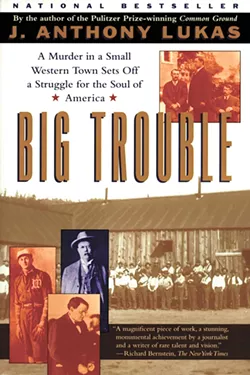

BIG TROUBLE

If this story has you Googling Wobblies and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn to learn more, you may want to jump right into the deep end and go ahead and read Big Trouble. Published in 1997, it flew under the radar at first. But for lovers of local history, especially the era around the time of the Battle for Spokane, it quickly became an influential piece of local history. Jess Walter kept it handy throughout the writing of The Cold Millions.

Author and journalist Anthony Lukas devoted his career to the class divide in America. His book Common Ground, about desegregation and busing in Boston, is one of the great works of long-form journalism. Then he set his sights on one of those trials of the century, when a founder of the Wobblies, Big Bill Haywood, was accused of the shocking assasination of former Idaho Gov. Frank Steunenberg. It all played out in a Boise courtroom in 1907 and kicked off nearly two decades of unrest, including the free speech protests in Spokane in 1909.

Along the way, Lukas takes so many side detours into the forgotten alleys of Western history, you'll be hooked through all 750 pages. Of particular interest to local readers is the detailing of the labor troubles in the Coeur d'Alene Mining District in 1899, when disgruntled workers blew up the mill at the Bunker Hill Mine. Gov. Steunenberg's subsequent brutal crackdown, most believed, was the reason he was murdered outside his Caldwell, Idaho, home in 1905 by a bomb rigged to his front gate.

Sadly, Lukas took his own life just before Big Trouble came out, so he never got to see how beloved his book would become in these parts. In an essay he wrote for the Idaho State Historical Society, he answered a question he was asked quite frequently by his East Coast friends: What attracted him to spend so much time on a mostly forgotten trial in a far-off city?

"Part of it," he wrote, "was precisely that these events of the century's first decade lurked just beyond the memory of living Americans."

And that may be the allure of The Cold Millions as well. There's something mysterious and satisfying about re-creating so seismic a time — a signature moment that was in danger of fading into the mists of obscurity.

— Ted S. McGregor Jr.