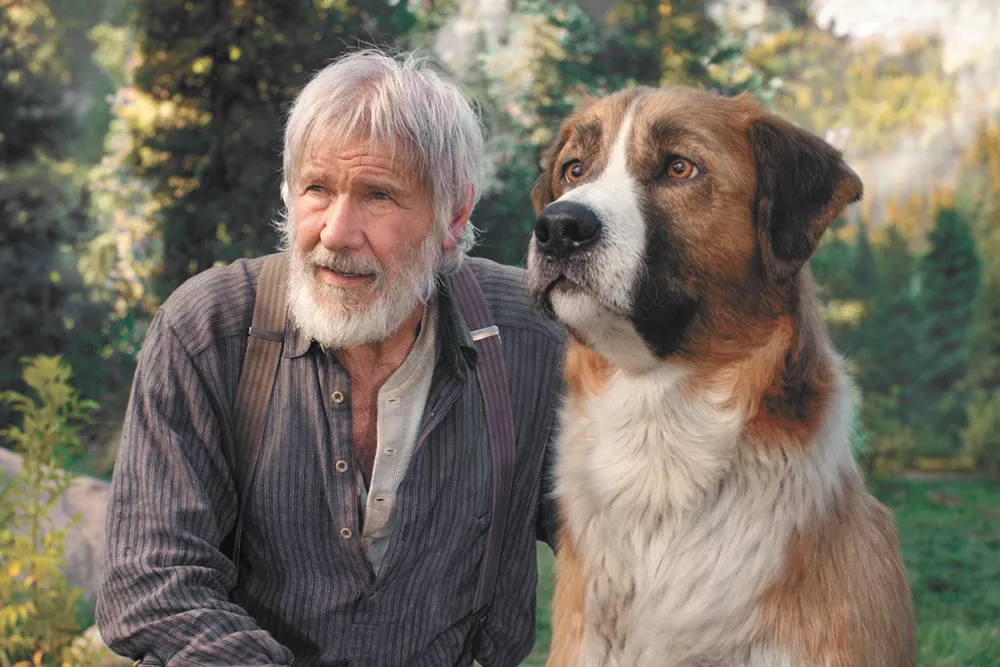

Harrison Ford has gone full Grizzly Adams and Buck the canine hero is fully CGI, 100-percent digital, not a scrap of real fur or dog farts about him. There is so much about this new umpteenth film version of Jack London's classic novel The Call of the Wild that is ready-made for meme-iriffic snarking.

Go ahead and get it out of your system, because dang if it ain't actually some old-fashioned kiddie-pitched action-adventure, sweetly earnest, equal parts scary and funny and exciting and sad and happy. It reminded me of the live-action Disney animal movies of the 1960s and '70s, the ones I grew up with. And if the kids at the family screening I attended are anything to go by — they loved it: the 6-year-old friend I went with was riveted, frequently leaning toward the screen at the intense bits — this new generation isn't too jaded to enjoy a cozy, sentimental story blazing on a big screen. Even one without catchy tunes.

I definitely had something in my eye several times while watching this. I'm such a soft touch.

Pitched for grade-schoolers this may be, but Call has not been dumbed down, nor are the harsher aspects of the tale elided over. And thank goodness for that. The rollercoaster of doggy emotions that Saint Bernard-Scotch shepherd mix Buck rides as he goes from pampered family pet in 1890s California to dognap victim to sled dog in the Yukon includes encounters with humans who run the full gamut from kind to cruel. More than one moment of mostly off-screen, mostly implied, yet still chilling violence toward Buck prompted screams of terror from the littlest ones at my screening. Call might be a tad too much for the youngest kids.

But none of the kids seemed to have any problem understanding that the stately black wolf that Buck keeps encountering on his journeys in the snowy wilderness is, in fact, the spirit of Buck's own animal nature, a guide for him as he rediscovers his untamed side. Some of the grown-ups I spoke to after the movie agreed with me that the ever-so-slightly cartoonish aspects to the all-CGI animals, including the other dogs on the mush team Buck joins, detract from fully buying into them as real animals. If there is a doggo uncanny valley here, it's in the very human, though also only very occasional and somewhat muted, rolling of eyes and other facial expressions that dogs don't actually make. None of this anthropomorphizing is anywhere near like the crime it can be in some for-kids animal movies; the dogs don't talk here, hallelujah. And it could be considered in keeping with the ethos of Jack London's novel: Part of the appeal of the so-called animal fiction of that era is a certain attributing to creatures' human motives, desires and feelings. I bet London would approve.

There are humans here. Ford's John Thornton is far from the only person to feature in Buck's adventures (even if the marketing suggests otherwise), and he has been given a somewhat different — and more poignant — backstory than the character in the book. In any case, apart from a few brief encounters with Buck early on and the gentle narration Ford's human supplies for our benefit, Thornton is not a significant friend for Buck until the final act. Ford is his usual gruff yet sneakily pleasant curmudgeon, and he displays a wonderful gameness in interacting with a co-star who wasn't there while they were filming.

Much as I love Ford, I would have been equally happy to see a full movie in which Buck continually exasperates his master (Bradley Whitford) in his well-off, comfortable California home. Or one in which Buck is just enjoying his work with the Canadian Post dispatchers (Omar Sy and Cara Gee) on whose sled team he ends up, and works his way up the pupper chain of command. (The casting of a French black man and a First Nations woman delivering mail in late 19th century Canada is how you do effortless diversity on screen. It's not even anachronistic!)

The Call of the Wild is a movie that, as noted above, is easy to dismiss and disparage. But now that I've seen it (and I wasn't expecting much), I feel like it's worth defending. For its empathetic soul. For its love of the natural world. Both of which need defending now more than ever today. ♦