When Hilary Anderson looks ahead to Coeur d'Alene's future, everything points in one direction: up.

The city population will go up. New, taller buildings will be built up. The demand for housing, and housing prices overall, will go up.

"We have a lot of people moving into the area," says Anderson, community planning director for the city of Coeur d'Alene.

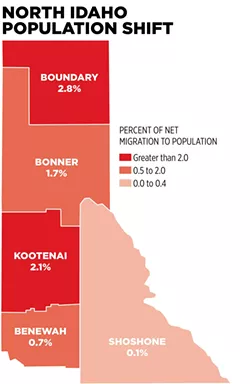

Coeur d'Alene is the fastest-growing metropolitan area in the fastest-growing state in the nation, U.S. Census Bureau data show. That metro area, the 11th fastest-growing area in the country, includes Coeur d'Alene, but also the rest of Kootenai County — Post Falls, Hayden, Rathdrum, Athol.

The city of Coeur d'Alene, currently with a population of about 51,000, is projected to reach 81,000 people by 2035, Anderson says. Post Falls, nearer to the Washington border, is growing even faster and at this rate would surpass Coeur d'Alene's population sometime between 2025 and 2027.

The growth is largely driven by people fleeing California or other Western states in favor of North Idaho's relatively low cost of living, outdoor lifestyle and, yes, the conservative politics. But along with the influx of growth arises more questions for politicians, developers and city planners, all bracing for what's to come.

"Hopefully," says Idaho state Rep. Vito Barbieri (R-Dalton Gardens), "we're not gonna see any high rises."

COMING CHANGE

From July 2016 to July 2017, Idaho grew its population by 2.2 percent — more than any other state in the country, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That represents an increase of about 37,000 people. Other states saw more of an increase in the number of people — Washington, for example, increased its population by 124,809 — but no state saw more rapid growth than Idaho.

Geographically, urban areas saw the most growth. In 2016, three of Idaho's metro areas ranked in the top 25 fastest-growing in the country, including Coeur d'Alene and Boise. And it's not a matter of births outpacing deaths. It's people, usually people 55 and older, moving to Idaho from places like California.

Barbieri says people want to get away from where they were living due to economic or political factors.

"People are recognizing, if you want to prepare against a progressive liberal agenda, then there are some places that may have a better chance of holding it off than others," Barbieri says.

All this growth promises to change the economy. Just as urban areas in Idaho are seeing population growth, they're also seeing most of the employment growth, says Sam Wolkenhauer, a North Idaho labor economist for the Idaho Department of Labor.

With the increase in baby boomers, health care jobs will become more in demand, he says. Construction jobs will open up, as will manufacturing jobs and service-industry jobs, he says.

Housing costs, too, will rise. Numbers from the Coeur d'Alene Realtors Association already show that the median home price rose 12 percent from November 2016 to November 2017, reaching $248,755. For people born and raised in North Idaho, that's a lot. For people coming from out of town? It's not bad at all.

Amanda Kuespert, an agent for North Idaho Real Estate, says that's why clients are drawn to the area.

"North Idaho's pull is that people want land and space," Kuespert says, "and not to be living on top of each other."

URBAN PLANNING

For cities like Coeur d'Alene and Post Falls, the influx of growth creates one major question: Where can the city expand?

And for those two cities, the answer is completely different.

In Coeur d'Alene, there's isn't that much space to expand, with the lake and mountains in the way, Anderson says.

"We are somewhat constrained," Anderson says.

So the city is updating its comprehensive plan, focusing on "infill," or development within the city limits instead of expanding outward. That could mean taller buildings, she says, with a variety in types of housing. People in Coeur d'Alene are interested in low-maintenance homes, without a yard to maintain, and condominiums, she says.

New homes will likely be constructed to the north on the prairie, moving away from Lake Coeur d'Alene. Coeur d'Alene Public Schools recently passed a bond measure that adds space to its high schools and will add a new elementary school on the north side of the school district that should open in 2019. Already, the district is trying to find property in anticipation for another new school on top of that.

"It's a situation where we're always playing catch up," says Stan Olson, Coeur d'Alene Public Schools superintendent. "What I'm trying to do is meet with developers and meet with municipalities and put this stuff on their radar screen."

To the west, in Post Falls, it's a different story. Realtors in Coeur d'Alene like Tom Torgerson are excited for the residential development taking place there.

"Post Falls has the most land mass to expand to," he says.

Since it's still considered "rural," home buyers benefit from a U.S. Department of Agriculture loan mean to support housing in rural areas. Post Falls is planning for an annual 5 percent increase in growth for the coming years, part of it fueled by the USDA loans, says city administrator Shelly Enderud. However, once the population reaches 35,000 in Post Falls, as it's expected to within the next few years, that benefit might expire for home buyers since Post Falls would no longer be "rural." Enderud says Post Falls may try to get an extension, but by 2020 it could be gone.

When that happens? Expect more development between Post Falls and Rathdrum, a city currently with less than 10,000 people, Torgerson says.

"I have a strong feeling that you're gonna see that market segment come in on the south end of Rathdrum," he says.

For the state, there's another consequence of growth that officials want to mitigate: traffic congestion. State officials with the Idaho Transportation Department, the city of Coeur d'Alene and the city of Hayden are gearing up for improvements to Highway 95, including smarter traffic signals and median crossings, aimed at reducing congestion.

State Rep. Luke Malek, R-Coeur d'Alene, doubts it will be enough. Statewide, he says, Idaho needs hundreds of millions of dollars in infrastructure improvements, and he says the state needs to do more than just maintenance. He says he's "eager to have a conversation" about how to find a revenue source to pay for infrastructure.

"Our infrastructure in the Kootenai County area is failing," Malek says. "It's going to be a major barrier to safety and quality of life."

For Anderson, with the city of Coeur d'Alene, this is the reality of planning for growth — managing expectations from all angles to provide the quality of life that those in North Idaho expect.

With all the change, she says, it may be a challenge to preserve the character of North Idaho. Even though everyone's looking up, she says, it's still important to stay grounded.

"We're going to work really hard to make sure we maintain the character that people love." ♦