"It was like winning the lotto," the middle-aged woman exclaimed from a DVD set on repeat in the lobby of the museum. "We had been searching for days. ... Then I looked under this overhang and there it was — a pot — in perfect condition!"

I looked past the monitor to a collection of pottery that was dated and numbered and housed in a temperature-controlled room meant to keep the clay earthenware from deteriorating. You could type the number of a pot into a monitor and learn about each artifact: the approximate year made, location found, and the name for the style of art colonial scientists had given it. I turned to go, and when I left the room, the lights shut off behind me.

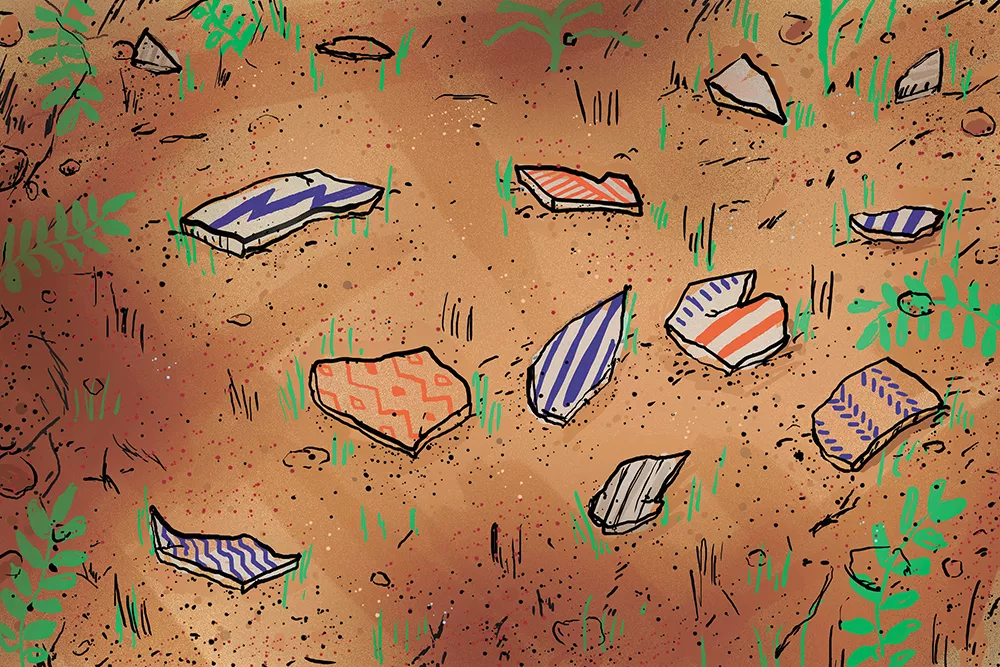

Earlier that week, my partner Caleb and I had walked a popular trail near Comb Ridge. Red rock. Desert country. My matrilineal homelands. We had seen a dwelling, art, a granary. We had gotten off trail though and were tiptoeing through cryptobiotic soil, trying to hop from rock to rock or follow game trails, so as not to do more damage to this land whose protections are lost and won depending on who is in office and what resources (money) might be pulled from the land. I was in a sea of the protective soil when I saw the first potsherd, then another, and another. Each as brilliant as the first. This one with a basket design carved into it, that one with black thunderbolts. I picked them up, admired them, turned them back to the earth. I was so entranced with what I was seeing that I nearly walked into the steel post that was driven into the tender crust and field of potsherds. Texaco was welded down its length. And a number that somewhere, I'm sure, correlated to the site's value.

Caleb came up beside me and we talked about the enormous truck that would have driven back here. The artifacts crushed beneath its brutish wheels. The ground shaking as the drill bit spun. In the house dwelling we had just left, where children's handprints were cast on red walls, I imagined mortar loosening. One rock falling from the wall, then another. What did their exploration find? Another lotto?

The museum has a pamphlet to help visitors understand what they were seeing. "Our cultural inheritance," it reads. It attempts to explain the meaning of petroglyphs and holds sketches of pottery. Lost in the text are the words of a Hopi elder that said when a pot cracked or lost usefulness it was shattered and returned to the earth that it came from to be born again. The field of potsherds was a burial ground; the Texaco marker a gross and impudent headstone.

"Bears Ears has always been protected," the woman at the museum gift counter told me as she rang up my sale. "All the media attention has people coming in record numbers. You used to be able to walk out anywhere and see hundreds of potsherds. Not anymore. People are filling their pockets with them."

Outside, the sun was bright against snow that had fallen the night before. I looked south at the land we had come from, where my mother's people had come from, land that was stolen and is robbed from still, bartered land, traded land, land hunted as if it is a game. ♦

CMarie Fuhrman is the author of Camped Beneath the Dam: Poems (Floodgate 2020) and co-editor of Native Voices (Tupelo 2019). She has published poetry and nonfiction in multiple journals as well as several anthologies. She resides in the mountains of west-central Idaho.