Augustin Hadelich is steeped in the repertoire of classical violin concertos and travels the globe to perform them with the world's major orchestras. The cosmopolitan violinist — born in Italy to German parents, now an American citizen — is also a proponent of modern works by a more current generation of composers like György Ligeti and Thomas Adès.

Some might see a contradiction in his embrace of old and new. But Hadelich identifies a certain freshness in all of these works. Before the classics became classics, they were often on the cutting edge of music.

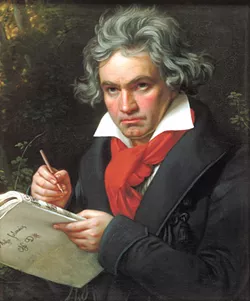

Beethoven's Violin Concerto is a prime example. First composed in 1806, it initially met with skepticism from the public as well as performers.

"The great composers were always pushing the envelope on the technical challenges that they threw at violinists of their time. By the time you get to Tchaikovsky and Sibelius, the pieces are more technical. You have to play octaves and double stops and other crazy things, which Beethoven doesn't ask for," says Hadelich.

"But in another sense Beethoven is much more challenging, because the solo part is so exposed that you're incredibly aware of every single note. If anything isn't totally perfect, it's quite obvious."

One possible reason for its stringency is that Beethoven was approaching the work as a pianist, not a violinist.

"Things that sound quite simple are really finger-twisters to play on the violin, which Beethoven didn't really care about. Or maybe he was aware that it was uncomfortable, but that would not have concerned him very much," Hadelich laughs. He recounts an anecdote about a violinist complaining to Beethoven about the impossible physical demands of his music. Beethoven supposedly replied that his source of inspiration, the gods, gave little thought to the violinist's miserable instrument.

After a lackluster debut, it wasn't until the concerto was championed some 40 years later by star violinist Joseph Joachim that its reputation was reassessed — although Beethoven was no longer alive to witness the revised reception.

"People were often confused by the new stuff he wrote. This piece has a kind of classical simplicity [but] it was very revolutionary at the time it was written in terms of how it advanced the form of the violin concerto. It's much longer, much bigger, much more grand than the concertos that had been written previously, and it has a violin part that's also much more exposed. You're often playing in the very highest register. It has very beautiful, delicate, luminous, singing lines, so it has its own kind of sound world," he says.

"Of course, now it's one of the works that every violinist grows up listening to and wanting to play."

Hadelich is scheduled to perform Beethoven's Violin Concerto this weekend as part of the Spokane Symphony's commemoration of the composer's 250th birthday. This marks Hadelich's first return to Spokane since 2011. Mark Russell Smith of the Iowa-based Quad City Symphony Orchestra will conduct the orchestra in a program that also features Beethoven's Egmont Overture and his Symphony No. 7.

Although the celebration of Beethoven's life and legacy might sound like it's geared solely to classical aficionados, Hadelich says its reach is much broader than that.

"It's music like this, the very greatest works in the repertoire, that touch our emotions in a way that doesn't require any expert knowledge. They weren't really written for experts. Sometimes with classical music, there's not as much instant gratification as if you went to a movie, but what you get out of it can be very meaningful and leave you refreshed and changed and better off somehow," he says.

"To someone who has never heard [the concerto], I think it's a particularly beautiful piece. It's not a difficult piece that showcases its difficulty. There's a transparency to it, a purity. It's almost not quite of this world." ♦

Masterworks 5: Beethoven's 250th Birthday • Jan. 18-19; Sat at 8 pm, Sun at 3 pm • $21-$66 • Martin Woldson Theater at the Fox • 1001 W. Sprague Ave. • spokanesymphony.org • 624-1200