Darryl Potyk, M.D., queues his phone to a song, presses play and deposits the phone in an empty, grande-sized paper coffee cup. He slides the now amplified phone to the center of a table and three people lean forward, intently listening to Neko Case's smoky voice, whisper-singing her cover of Tom Waits' "Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis."

The song ends. The group leans back in their chairs, and Potyk asks the two men and one woman, "What did that song mean to you?"

It's sad and bluesy," Jessica Lundgren offers. "She's pregnant, she's broke, then we find out she's in prison... "

"I hear poverty and struggle, something I don't know a lot about firsthand," says Dan Rona-Hartzog.

"I hear the Western perspective coming through," Mark Joseph Torres says, reflecting on his upbringing in the Philippines. "She's worrying about the future, thinking ahead."

We are not in a high school literature class, group rehab or college seminar on music appreciation. And these are not typical students. We're in the physician's breakroom at Sacred Heart Medical Center, and today the participants are a senior and junior resident, a third-year medical student and an attending physician. Dubbed "A Daily Dose of the Humanities," the innovative exercise incorporates art, music and literature into medical education at the University of Washington School of Medicine regional campus in Spokane.

Humanities classes are rarely offered in medical curricula; as electives, if they're available at all. Most medical coursework is so intense and packed with science and medicine, the last thing a fledgling physician will choose to do is sit in on a class involving art, literature or philosophy. But years ago, as medical school course developers realized that an education focusing only on the nuts and bolts of medicine could end up producing technically proficient but robotic physicians, humanities course offerings in medical school began to gain traction.

On a daily basis in clinics and hospitals across the country, electronic medical records have served to further widen the disconnect between patients and their health care providers. EMRs require doctors to spend precious appointment time on the keyboard of their laptops documenting the visit. Patients say they feel disconnected, unheard and dismissed when physicians are constantly looking at screens, busily typing chart notes.

A Daily Dose of the Humanities offers a way to help medical professionals reconnect with their patients, their peers and themselves. It differs from traditional coursework in two important ways: it's short and it's daily. Prior to patient rounds at Sacred Heart, the internal medicine rounding team (usually an attending physician, residents, medical students and occasionally pharmacists) meets for about 10 to 15 minutes, and one member shares a piece of music, art or literature. The exercise is the catalyst for a group discussion as each team member reflects on how they personally feel the art or music applies to medicine, patients or themselves.

The innovative program, which began two years ago, is the brainchild of Potyk, Assistant Dean for Regional Affairs and Clinical Professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Spokane. Potyk is quick to share credit with Judy Swanson, M.D., Internal Medicine Clerkship Director and Clinical Associate Professor; Judy Benson, M.D., Providence Internal Medicine Residency Program Director and Clinical Associate Professor; and Jeremy Graham, D.O., Clinical Assistant Professor, all at the UW School of Medicine. Potyk's medium is music, Benson and Graham focus on literature and Swanson concentrates on visual art.

"The short, intense humanities sessions allow everyone to take a breath, look at the big picture and reflect for a moment on why they became doctors," says Potyk, an instructor at the UW School of Medicine since 1994. "Discussing a piece of art, a song or literature lowers barriers and allows us to glimpse into another person and discover other lives. We ask each other, 'How does this speak to you, to what we do every day?' "

One of Potyk's Daily Dose exercises revolved around the Neil Young song "The Needle and the Damage Done," a poignant lament of heroin addiction.

Potyk notes that even though the song is 45 years old, it has a timeless message about the compelling lure of drugs in today's society. When he presented the song to the internal medicine rounding team he was leading, he says it opened the door to discussing the tug and pull of treating patients who use illegal drugs, the need for compassion on the part of their medical providers and the physician's responsibility to prescribe appropriately and limit narcotic prescriptions.

"Additionally, some took note of the line, a little part of it in everyone," Potyk says, "highlighting our own vulnerability, which led to a discussion of impaired physicians, the incidence of substance abuse and what to do if you suspect a colleague is impaired."

Not all musical discussions are quite so heavy. Molly Knox, a fourth-year medical student entering the field of neurology, presented four songs during her four-week rotation, but one stands out.

"I was in the fourth week of my first rotation of medical school and the residents were finishing their very first block of inpatient service," Knox says. "It had been a long week with challenging cases and late hours. So far that week, we had serious discussions following mainly sad songs. To lighten the mood and celebrate the end of our first block, I brought in a pump-up rap song (often played during hockey games). It had the desired effect — laughter — but also began a short discussion on coping with stress."

"Songs have the ability to say what we sometimes can't — that we are sad, having a bad day, confused or upbeat," she continues. "Taking a few minutes before rounds to relax and express ourselves was therapeutic and led to team bonding. The humanities program also facilitated the team to process patient cases: if there was a difficult case keeping you up at night, the scheduled time prior to rounds was a great time to debrief."

When Galia Deitz, a third-year medical student, first learned they would discuss artwork every day before rounds, she was ambivalent.

"I didn't realize this was not something every team did until we had a different attending physician," says Deitz, who participated in the Daily Dose for one week on Dr. Swanson's team.

"Much of medicine is built on laws and universal understandings of science, and that is what guides clinical judgment and decision-making," Deitz says. "However, there is also an important, intangible component to medicine that extends beyond science and can also be influential in driving medical decisions. A lot of art interpretation is just that: interpretation. We use visual cues to help us gain a better understanding of what message or meaning we think the artist is trying to convey. The same is true with medicine. We use observational skills, a large one of which is visual, to help guide patient interviews, the tests that will be ordered, and the diagnoses that will be included in our differentials. Whether this helps us come to the correct diagnosis, or simply establish rapport with a patient, it is an invaluable art."

Swanson, who has been teaching since 1998, uses art to generate discussions with her care delivery team. "I am big on observation and physical diagnosis," she says, "and my goal using visual artwork in this program is to reinforce physical examination skills and help students see the whole patient, not just the ailment."

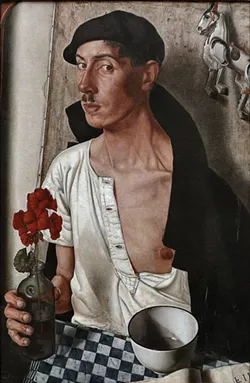

Swanson presented a Dick Ket painting to open the discussion of looking for visual cues. In the Dutch magic realist's self-portrait, you see a thin, dark-haired man holding a bottle filled with flowers. He wears a black beret, a white shirt unbuttoned below his chest and a dark coat slung over one shoulder. His head is turned away, but he looks at the viewer from the corner of his eyes.

"The portrait seems fairly straightforward, but when I asked the group to look closer, they realized his bluish nails and clubbed fingers demonstrated that Ket probably suffered from uncorrected Tetralogy of Fallot, a congenital heart defect which is present at birth," says Swanson. "The ensuing discussion emphasized the importance of including observation along with routine physical examination.

"Talking about what we see in an image," she continues, "opens up discussions on patient care. In our work, we see a lot of suffering, and sometimes what we experience working with patients is too raw to discuss outright. Daily Dose is a way we can let others know they are not alone in feelings of despair."

Empathy, despair, bonding. And sometimes perspective. During Ashton Kilgore's internal medicine rotation, she contributed an oil painting of a foot by Adolph Menzel. The appendage is seen from above, as if the viewer is looking down on their own foot.

"I like this piece for its skillful portrayal, the way it maintains the physicality and process of painting, and also because of the perspective from which the foot is painted," says Kilgore, a fourth-year medical student. "While medical studies are largely focused on pathologies, physiology, diagnoses and treatment, seeing this foot from a patient's perspective served as a good reminder for me to consider the emotional and social concerns of my patients."

Participants are also invited to contribute their own artwork to the Daily Dose. Kilgore, who grew up in the Congo, Kenya, Morocco and Haiti as the daughter of a bush pilot, offered a sketch of Congolese pygmy children that she had drawn when she was 22 years old. Her time spent in poverty-stricken areas of Africa and the Caribbean largely influenced her decision to go into medicine, as she witnessed firsthand the disparities in health care between the United States and developing countries.

Her sketch not only spurred a conversation about the types of illnesses and disease she witnessed in Africa, it also gave the other students and residents a portal into Kilgore's talent as an artist, and helped round her out as an individual as well as a fellow medical professional.

The residents and students interviewed unanimously agreed that the Daily Dose is a welcome respite to their hectic schedules, an enlightening team-building exercise and an eye-opening opportunity to examine their own philosophy on the practice of medicine.

"The Daily Dose of Humanities is a great way to remind young doctors and doctors-to-be that with all things in medicine, never stop learning how to be a compassionate human," says Knox. ♦

"The Needle and the Damage Done"

I caught you knockin'

At my cellar door

I love you, baby,

Can I have some more

Oh, oh, the damage done.

I hit the city and

I lost my band

I watched the needle

Take another man

Gone, gone, the damage done.

I've seen the needle

And the damage done

A little part of it in everyone

But every junkie's

Like a settin' sun.

— Neil Young, 1972