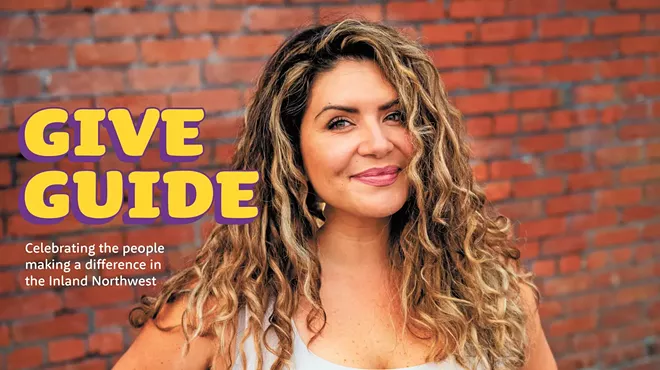

After starting at the Lands Council in 2009, one of the first job requirements Amanda Parrish had was to become a certified beaver trapper.

The Lands Council had started working to relocate nuisance beavers to areas where their ingenuity would be better appreciated and needed, as their dams can actually work to restore much-needed habitats.

"In so many ways, this one animal is a really important part of the North American landscape," Parrish says. "Beavers, through the dam building that they do to create their own habitat, are creating habitat for a number of other species. It's keeping water on our landscape longer, it's creating wetlands, which act as a water filtration area. Beaver dams are also sources of wildfire breaks."

Parrish relocated to the Inland Northwest in 2008, when she hopped in the car the day after graduating with an environmental science degree from the University of San Francisco and headed to Worley, Idaho. There, she worked for the Coeur d'Alene Tribe, before soon finding work with the Lands Council.

In that early Lands Council role — "my parents loved that my business card said 'Beaver Program Director' for a while" — Parrish would literally take her work home with her sometimes.

"Our first beaver holding facility was in my backyard in the Perry District," she says.

Beaver families would wait in an enclosure in her backyard before getting relocated to other areas like the Colville National Forest.

Parrish then served as the watershed program director for several years and later took on the job of operations director, keeping track of the books and learning about every cent that flowed in and out of the organization.

Twelve years after starting, Parrish is now the executive director, and hopes to continue growing the Lands Council's many diverse programs with an emphasis on addressing climate change and working to find more on-the-ground environmental solutions in North Idaho and Eastern Washington.

"My vision for the Lands Council going forward is that we really center environmental justice and climate change solutions into all of our work," Parrish says. "I want to make sure that the Lands Council is poised to move quickly on action that needs to be taken, because we just have very little time as a society to make drastic greenhouse gas reductions."

Even as executive director, Parrish is still taking her work home with her. One of the Lands Council's latest projects is testing how biochar — a charcoal made from heated organic material — can be fine-tuned to work in the Inland Northwest.

"Biochar is enhanced compost — it's organic material burned at a high temperature in the absence of oxygen," Parrish says. "It's great for restoration, and it's used in agriculture because it adds a lot of organic material to agricultural fields."

But one of the tricks is figuring out how to make biochar from Eastern Washington biological material, like the slash piles left after logging, since much of that material in this area includes pine needles. Those needles create a lot of smoke, Parrish says, which can contribute to air quality issues and release the greenhouse gases that biochar is intended to sequester.

"If we want to have biochar sequestering carbon, there needs to be a low smoke point," Parrish says. "If it adds to another problem like atmospheric carbon or air quality, it's not a helpful solution."

So, on Aug. 19, Parrish picked up and installed biochar kilns in her own backyard that will be used for further experimentation as the Lands Council continues looking at the problem.

Parrish notes that many of the Lands Council programs start by addressing an issue directly, which can help illuminate current barriers to progress. Then, the staff of six to nine people (depending on funding) can work to change laws or find resources to make environmental restoration work easier for everyone.

For example, through the beaver program, Parrish says the council was able to take what was initially just a Washington Fish and Wildlife program to relocate animals that were bothering property owners, and help pass a state law to intentionally use relocated beavers as agents of restoration.

"This is the story of a lot of things the Lands Council has done. The role we play is to advance solutions around the environmental issues we believe in," Parrish says. "We're never going to be a major player in beaver relocations or a major producer of biochar, but we can see what obstacles we come into contact with that keep us from advancing this solution, and what are the regional Inland Northwest variables coming into play?"

Recently, the council hired social scientists from the University of Idaho to interview regional farmers to see what obstacles still stand in the way for those who haven't volunteered to plant trees and other shade plants that can help fish moving through waterways that cut through their properties, such as Hangman Creek.

"We've already worked with the landowners who voluntarily want to work with us. We want to see, what are we missing, what are the obstacles to adopting riparian buffers?" Parrish says. "I want to hear from the farmers: What am I not thinking of? How can I change not only my language, but the sort of policy the Lands Council advocates for?"

The council has also partnered with the city of Spokane to plant neighborhood trees at properties with homeowners and tenants who are willing to help water those new plants as part of the SpoCanopy project.

The city intends to increase its tree canopy coverage to 40 percent by 2030, as trees provide benefits such as needed shade and cooling during the warmer months, on top of beautifying neighborhoods.

"Just as in so many communities around the country, here in Spokane low-income neighborhoods and neighborhoods that were traditionally redlined are not so coincidentally lacking in tree cover," Parrish says. "That has environmental justice implications, and it means increased utility bills in the summer because you have no shade to cool your house."

The program will plant hundreds of trees every year. This fall the Logan Neighborhood will see 160 new trees planted under the program, and West Central has also benefited from the program, she says.

(As an aside, Parrish is pretty familiar with plants as she not only makes time to run the Lands Council, but also owns the floral and plant shop Parrish and Grove.)

Two of the largest volunteer opportunities the Lands Council hosts each year are coming up soon. You can sign up ahead of time (which is preferred) or just learn more about each event by visiting landscouncil.org or following the Lands Council on Instagram and Facebook.

On Sept. 18, the Lands Council will host its annual Spokane River cleanup day, when hundreds of volunteers usually remove several tons of trash from the river, with teams working sections of the river from Stateline to Spokane Falls.

Then on Oct. 23 they'll host their annual Reforest Spokane Day, when volunteers will plant thousands of trees in a single day.

Or, if you're looking to really devote time and take on a career in this work, Parrish says she hopes the Lands Council will soon be able to hire a climate justice program director. ♦