It only takes a few seconds. You leave your car warming up in the driveway before work, or maybe you parked that trusty old Honda on the street overnight. Thieves have learned that almost anything — a shaved key, screwdriver, kitchen fork, rake tine — will pick the lock and start it up.

Property crime continues to be a problem in Spokane and across the state, and vehicle theft is a major contributor.

In 2016, the most recent year for which official data is available, Spokane police took in reports of 1,992 vehicles being stolen in city limits — a figure that's held relatively consistent for the past five years.

That's a rate of about 931 vehicles per 100,000 people, or an average of about five stolen cars per day. Detroit had the highest 2016 vehicle-theft rate in the nation (1,330 per 100,000 people), and Portland's rate is good for third among major cities (767 per 100,000).

For police, frustration lies with the justice system's revolving door. People who've racked up five, six, seven or more vehicle thefts are released on relatively low bonds, in part because their alleged crimes are nonviolent. Then they're re-arrested again before the other charges are resolved, yet might not serve additional time for the subsequent crimes.

"Once these people are adept at stealing cars and driving them around for a few days, we catch 'em, but how many more are they responsible for?" asks SPD Capt. Brad Arleth. "Without some physical evidence or an admission, we don't know about the other potential 15 in the past month."

For prosecutors, one of the major hurdles for vehicle-theft cases in the courtroom is proving that a person knew the vehicle was stolen, says Spokane County Deputy Prosecutor John Grasso. Often, a person found in a stolen car will say they borrowed it from a friend. They had no idea the car was stolen, they'll tell police. Without other evidence, that can make the crimes more difficult to prosecute.

But perhaps the biggest frustration of law enforcement is the fact that Washington state does not supervise vehicle thieves (and other property crime offenders) after they're released from prison.

"I've been here long enough to remember when they still supervised property offenses," Grasso says. "I'd give up jail time in exchange for community supervision."

Last year, officials began looking for ways to curb the high rate of vehicle theft in Spokane.

Last January, SPD dedicated a team of five officers whose primary focus is searching for stolen vehicles, and catching the people who steal them. Additionally, a bill introduced last year in the state legislature would create a pilot program in Spokane where people convicted of vehicle-related felonies would be eligible for community supervision. Police and prosecutors are hopeful the bill passes this session.

"Vehicles are the center of so many crimes: drugs, guns, robberies, residential burglaries, vehicle prowling," says Sgt. Kurt Vigesaa, who leads the team of SPD cops focused on vehicle theft. "They are a crime mode of transportation."

The temporary license plate in the rear window tips him off — a common tactic vehicle theft suspects use to conceal their crimes.

Vigesaa pulls behind the silver Chevy Malibu and flips on his lights.

The suspects counter. Rather than pull over, the Malibu speeds off, and there is nothing Vigesaa can do but watch. SPD's internal policy bars officers from getting into vehicle chases if a stolen vehicle is the only suspected crime.

"And they know it," Vigesaa says. "They'll play the games. Get behind us. Wave and take off. All we can do is wave at 'em."

But shortly after the vehicle flees, Vigesaa spots the two men, who he saw driving the car, now walking a few blocks away. A citizen saw them park it and pointed Vigesaa in the right direction.

When police arrest the men, they say, "They were nowhere near any car," Vigesaa recalls. "That they were just out walking, getting exercise."

Police and prosecutors hear stories like that all the time. They can represent a major obstacle in the courtroom.

Grasso, the deputy prosecutor, gives this example: A person is stopped in a stolen car, but has the key to the car. The suspect tells police he borrowed the car from a friend, but declines to say who that person is. Without some circumstantial evidence, such as a history of stealing cars, a "punched out" ignition or further damage, "that might be a hurdle too great to overcome," he says. "Sometimes there's no way for us to prove they knew a car was stolen."

In this case, the suspects denied even being around the stolen Malibu, yet police found the car's key in one of the men's pockets. They found a small baggie of meth and a 9mm pistol as well. Drug addiction is behind so much car theft in Spokane, Vigesaa says.

"I saw 'em driving it," he says. "It's my word against theirs."

Police call the victim to retrieve the car. It was stolen back in October 2017, and she never thought she'd see it again.

"Can you notice much difference to it?" Vigesaa asks the woman. "That stereo, is it new?"

"That's not mine," says the woman, who declined to give her name out of fear for her safety. "All my stuff is gone. There's a different stereo, and it has a lot of body damage that it didn't have before."

"Standard," Vigesaa murmurs.

By now, she says she's purchased a new vehicle.

"It's been hell because now I have car payments, which I didn't have before," the woman says. "I'm a single mom of two. I work 40 hours a week. I work my ass off to take care of my kids, and unfortunately Spokane's drug problem has affected my life, which sucks."

Vigesaa speaks in clipped sentences. His graying crew cut lends credibility to his frustrations arresting people — some with 20 and 30 felony convictions — only to watch as they're released with "no accountability."

He points to these examples:

Adam Rusho was arrested in January and charged with three counts of taking a motor vehicle. He was released from jail without a bond the day after his arrest.

"Is this a deterrent that will keep him from immediately going out and stealing more vehicles?" Vigesaa asks.

Rusho was initially caught stealing Hondas, Vigesaa says. Since the man's release, "there have been eight stolen Hondas that I am aware of," he says.

Richard Hoffman pleaded guilty last spring to eight charges including theft of a motor vehicle, trafficking stolen property and burglary. His criminal history includes similar crimes — all nonviolent property and drug offenses — dating back to 1990.

In the most recent case, Hoffman stole a pickup truck and more than $100,000 worth of equipment from his former employer. The 42-year-old was sentenced to 36 months in prison, where he'll get drug treatment.

Hoffman's earliest release date is November of 2020, according to the Washington State Department of Corrections, though that includes a sentence out of Whatcom County as well.

"I know the judicial door is a rotating door and people are in and out," he says. "We arrest people with 10, 15, 20 felony convictions all the time. If we can take some of these vehicle thieves off the street for a few days, that's a couple days they're not victimizing citizens."

Since January 2017, the team of five officers under Vigesaa's command have recommended 184 felony charges to prosecutors, 121 of those were for vehicle theft or possession of a motor vehicle.

His team also found 83 stolen vehicles with someone inside, "which may not sound like a lot to you, but some cops don't ever recover five occupied stolens in their career," Vigesaa says.

Indeed, SPD has been pretty successful finding stolen cars. In 2015, for example, officers found 1,593 out of the 1,746 vehicles reported stolen, according to numbers provided by the department. What's more difficult is figuring out who actually stole the car.

That's why the vehicle-theft team has began fingerprinting recovered vehicles "in the hopes of identifying suspects who are taking more than one or two vehicles within a certain area," says Arleth, the SPD captain.

Vigesaa can't help but look for stolen vehicles. It's dark now, and raining on a Tuesday evening in Spokane. Vigesaa's unmarked car creeps slowly over the damp pavement in the city's northeast neighborhood. Many stolen vehicles end up on the north side of town, he says.

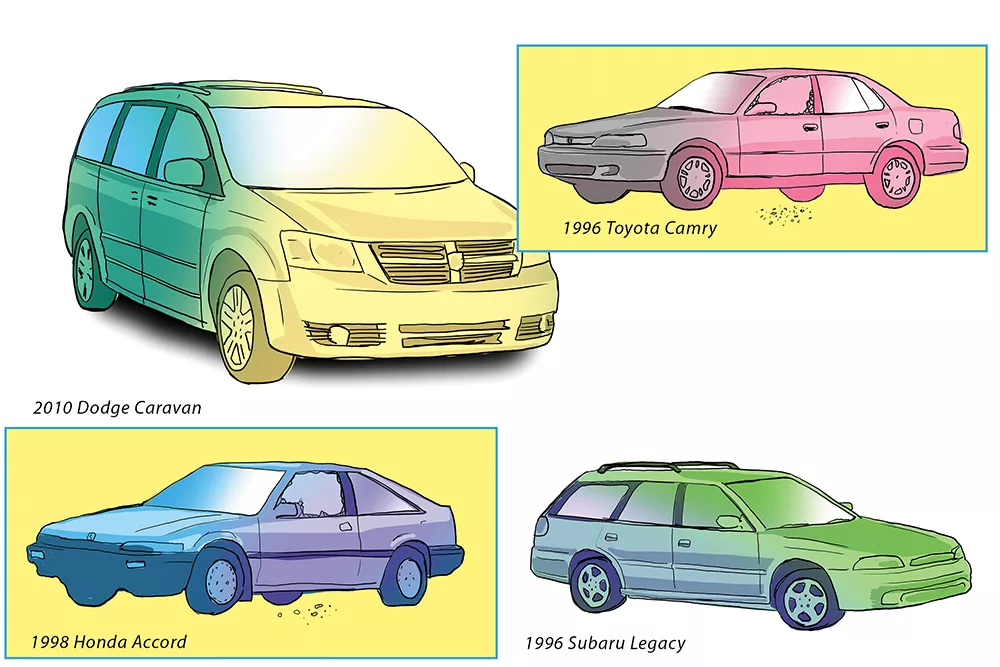

He parks out from under the glow of street lights, and opens his computer revealing the list of about 30 or so cars currently reported stolen in Spokane — lots of Hondas, Toyotas and Subarus.

He starts to flip through photos on his phone: One shows a pocket knife jammed into a car's ignition, which was used to start it; another is of a metal rake tine that he pulled out of an ignition.

"The older [cars], because they have worn out ignitions, criminals will use shaved keys, screwdrivers, knives, kitchen forks, rake tines," he says. "That's a unique Spokane thing — metal rake tines. You name it, and I've pulled it out of ignitions."

He turns back to the computer when something catches his eye in the rearview. A Honda Civic with a busted out back window scoots past his unmarked car and turns right. Vigesaa types the plate number into his computer and the results intrigue him. He throws the car in gear and the V8 roars to life.

"That's probably a '93 Civic," he says. "The plate belongs to a '92 Ford."

The Civic pulls into a gas station and Vigesaa follows close behind. The driver says he forgot his license at home. He tells the sergeant his name, birthdate and address.

"He's lying to me," Vigesaa says when he gets back to his car. Turns out, the name matches someone with a Washington state license, but it's not the guy sitting in the driver's seat.

The car hasn't been reported stolen, but the passenger said she recently bought it "from a well known criminal, who we know, who steals cars," Vigesaa says.

Eventually, police find the man's real name and arrest him for a warrant out of Idaho.

It seems obvious that lying will only delay the inevitable, that police will find out who the guy is, so why lie?

"He doesn't want to go back to Idaho," Vigesaa says. "Idaho is tough on crime, unlike Washington."♦