It's dinnertime at Kendall Yards. The vendors at the Night Market are hawking cinnamon rolls, coffee cakes and hot dogs, as the customers line up at food trucks to order BBQ brisket and Asian cuisine.

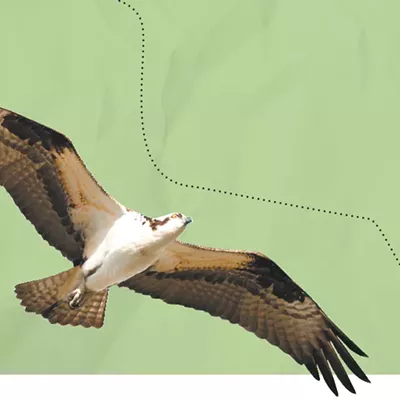

But the osprey I see patrolling the canyon has spotted a different sort of dish. In an instant, he snaps down beyond the treeline, diving toward the Spokane River. He emerges mere moments later, triumphant, a huge sucker fish — maybe a foot long — speared in his talons.

But instead of returning directly to one of the towering nests that line the Centennial Trail in Kendall Yards, the osprey takes a victory lap. With the limp fish still skewered in his claws, he glides through the Spokane skyline, above the homes in Peaceful Valley and up, up, up, over the commuters crossing the Maple Street Bridge. He soars over downtown Spokane, flapping past the Steam Plant chimneys, the spires of the Cathedral of Our Lady of Lourdes, over the roofs of Nordstrom and City Hall. Then it's back across the river, back to the Night Market, directly over my head — through my telephoto lens, I can see the red rivulets of blood run down the fish's white belly and across its silver tail — then off to the west, toward the setting sun.

That's Spokane for you. Our sublime former slogan — Near Nature, Near Perfect — was mocked for the modesty of the phrase's second half. But the first half undersold the city as well: We're not just near nature. Nature is here, even in the heart of the city.

I'm not just talking about squirrels bounding along power lines or the ducks and geese that frequent the waters of Riverfront and Manito parks.

Browne's Addition neighbors sometimes see deer munching on their front lawns, just a few blocks away from the city center. Gangs of wild turkeys invade backyards of South Hill neighborhoods. On occasion, a moose will blunder into a pool or elementary school.

"The raccoons and coyotes will attack household pets and small livestock," warns a letter to new Peaceful Valley neighbors.

And then there are the marmots. So very many marmots.

ROCK THE MARMOT

Even across the Spokane River gorge, you can see little brown dots speckling Glover Field in Peaceful Valley. Up close, you see why: The field is often teeming with dozens of marmots — sometimes as many as 40. They scamper across the baseball diamond. They squeeze under holes in the chain-link fence and crawl up on the logs hanging over the water. They stand on their hind legs and wrestle with each other and roll on their bellies giddily in the dirt.

I lay on my stomach to get a better picture, and watch a marmot scamper up to my backpack to paw and sniff at the zipper.

You want to see marmots? Here there be marmots.

Urban marmots are almost entirely unique to Spokane, says Elizabeth Addis, assistant professor of biology at Gonzaga University. She's heard of urban marmots in Boise and the Tri-Cities, though marmots generally aren't considered city dwellers. But here they are, gentrifying the center of Spokane.

It's why, back in 2014, Addis conducted a study to try to understand what was so special about Spokane marmots.

"I decided to explore, to see if I could figure out what is it about marmots that allow them to live amongst people," Addis says. "How are they doing so well in an urban environment?"

Her team trapped marmots in the city of Spokane — at Mission Park, Highbridge Park, and near the Red Lion Hotel, among other locations — and marmots in more rural areas, baiting them with apples, dandelions and ramen. Then her team compared the levels of stress hormones, called glucocorticoids, in the feces of the urban marmots and the rural marmots. There was no difference.

"It suggests that the urban marmot is not stressed in comparison to the rural marmot," Addis says.

So finding marmots is easy. Look near rivers, particularly amid big piles of rocks. In fact, right now, some of best places to find marmots are near the best places to spot ospreys.

At dusk, marmots stand like sentinels on watchtowers in the boulder-strewn lot next door to the Inlander offices. They bound across the dirt and slide under shipping containers holding construction supplies. One ventures out and places his tiny marmot paws on a pipe.

Don't make any sudden moves. Approach slowly. Don't let the marmot see you as a threat. Let her see you as a curiosity. Watch her watch you watch her.

Finding other urban wildlife is mostly a matter of luck, but you can increase your chances. Seek out the borders where the urban landscape turns to wilderness, like at High Bridge and Palisades parks. And get out of your car, where you're unlikely to spot animals that aren't dead on the side of the road.

Last July, I set out on a single bike ride home from the Inlander offices in Kendall Yards, west on the Centennial Trail, then south on Government Way. Along the way, I snapped pictures of five osprey, a quail, a buck, a doe and three separate groups of wild turkeys.

MAN VS. WILD

There are problems, of course, that arise when animal visits man. Ospreys snag koi fish from backyard ponds. Wild turkey droppings may have given a local toddler salmonella poisoning.

"I have a colleague where the marmot was actually eating part of their garage," Addis says.

Back when my dad was the track coach at North Central High School, he became locked in a Caddyshack-style feud with the marmots who were chewing through the school's pole vault pit. (And no, poisoning them with antifreeze doesn't work.)

But the stories these animal occupiers provide are worth it. I could tell you about the goose who began squatting in the osprey nest near Bridge Avenue, honking like he owned the place.

I could tell you about the time last year when I stalked a posse of turkeys through a neighborhood off of Government Way, dismounting from my bike to get a better photo. But as I held my breath trying to focus, I suddenly heard a high-pitched yeep! I turned around, and there, blocking my escape route to my bicycle, was a fearsome Spokane turkey. I'd been outflanked. Clever girl.

Or I could tell you a sadder story. Every so often, I visit the small family of marmots living in a burrow near the goose-occupied osprey nest. One day, I arrive to find a tiny marmot pup stretched out front of the burrow, belly up, mouth open, not moving. Flies flit about the marmot's vacant eye. A splash of dried blood lingers on the rock next to its head.

And then I see the dead marmot's family members pop out of the burrow. They stare ahead. They look weary, almost sad. That's the essence of the cruel beauty of nature: Sometimes majestic, sometimes adorable, sometimes just plain brutal. ♦