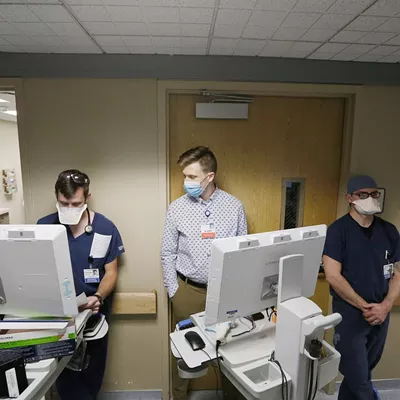

Nearly a dozen medical staff wearing surgical masks crowd in the hallway of one of Spokane's busiest intensive care units on Friday morning as they strategize treatment for an unconscious patient.

Her body is heaving for air as the team of residents, nurses and ICU medical director Dr. Ben Arthurs makes the morning rounds, getting updates on the severely ill patients in MultiCare Deaconess' COVID-19 unit of the ICU.

Several other patients here Sept. 17 are in even worse shape. Their bodies, desperate for oxygen, are not visibly gasping for air because they're paralyzed with medication so they don't disconnect the ventilators that are breathing for them.

The staff, pushing computer carts with patient chart information as they go, update Arthurs on a laundry list of medications, blood levels and often declining health status for each COVID patient here. They huddle outside the glass doors of each room that's been converted to negative air flow, forcing air into the patient room whenever the door is opened, to reduce the risk of transmission.

Outside one room, Arthurs dons a disposable yellow gown, face shield and a more protective N95 mask to change the settings for a man on a ventilator, as a nurse adjusts additional settings on a stand of medical equipment outside the room delivering several medications and fluids via drip lines.

That equipment is run on long tubes out to the hallway to reduce how many times staff have to go into each room, the nurse says, because they're constantly beeping with alarms, needing bags changed out and getting regular cleaning.

As Arthurs exits the room a few moments later, he asks a nurse, "someone was trying to get ahold of me?"

"Yeah, I got a call from the 11th tower charge. There's a patient up there they asked for an ICU bed for," she replies.

Do they have a bed? Arthurs asks the group around him. More importantly, do they have the staff? With patients who need this level of care, nurses would typically only have to oversee one or two people. But now they're having to run between the many needs of three intensive care patients at a time.

The flotilla moves on to the next patient update, but Arthurs is soon interrupted as another nurse says a patient on another floor of the hospital is on the verge of crashing. Before long a surgeon pops in to update Arthurs on a different patient. Then there's another update as the man upstairs is rapidly declining.

"In theory we round and we go to each patient and see them before noon," Arthurs tells the Inlander. "But when it's crazy like this, rounds include me getting interrupted four times in a presentation."

On these long, 12- to 16-hour ICU shifts, Arthurs has also been spending three or four hours per day calling families as he discusses the difficult reality that after 20 or 30 days on a ventilator, their loved one may never get better.

"And they have to make those tough decisions over video chat," Arthurs says. "It's hard. It's much easier when they are here and they can feel this a little bit."

The delta variant has changed the game for the worse as Inland Northwest hospitals are filling up with a record number of younger and younger COVID patients. Idaho hospitals have entered crisis standards of care, with some patients getting beds in conference rooms, while others are experiencing staffing and supplies at a level usually considered unacceptable. Washington hospitals are also nearing a breaking point, with Spokane's hospitals halting all non-emergency surgeries to free up capacity for the sickest patients.

While the COVID surge continues, cancer patients aren't able to get tumors removed, people suffering heart attacks are sometimes waiting hours in the emergency room before they're able to be seen, and people who've long been waiting for things like knee and back surgeries are being told it could be months before that can be scheduled.

Hospital staff who normally work in administrative jobs are being asked to scrub toilets, clean rooms and work cafeteria shifts to ease the burden on overworked nurses and support services staff.

Meanwhile, health care workers, already exhausted from working through a pandemic for 18-plus months, are now dealing with the worst rate of admissions and deaths yet. Nurses are being asked to work extra days. Some aren't taking more than a 10-minute lunch break in a 16-hour shift, while others make sure to drink most of their water for the day before they start work so they don't have to run to the bathroom later on.

"Imagine caring for 750 people dying over the last 18 months," says Peg Currie, chief operating officer for Providence in Eastern Washington, in an update to reporters. "That's equivalent to [more than] five 737 plane crashes in Spokane alone."

Unlike the winter hospitalization wave, when the majority of patients who ended up in the ICU were older adults or elderly, Arthurs says this wave has seen patients in their 30s, 40s and 50s ending up on ventilators, many of them so sick they need dialysis and other extreme measures to stay alive.

"If it's younger people, six months ago we were seeing 50 to 60 percent getting through. If it was older people, it was more like 20 to 30 percent," who survived after being put on a ventilator, Arthurs says. "Unfortunately what we've seen the last month is we're getting people who are so sick ... I don't think they've had a success story in three or four weeks."

"Imagine caring for 750 people dying over the last 18 months. That's equivalent to [more than] five 737 plane crashes in Spokane alone."

As he's answering another question from the Inlander, Arthurs and the medical staff are suddenly called upstairs to urgently intubate a patient with a breathing tube, and an eerie hush falls on the ICU unit.

The sad reality for these extremely ill patients is most of them will die, and it will have been an isolated, lonely death, surrounded by strangers.

These patients can't have in-person visitors until it's clear they're going to die. Their family can't offer them physical touch while they're being treated. Some families are begging nurses and doctors to simply hold their loved one's hand for a moment each day, so they feel something.

"We're setting up iPads and family members are Zoom-meeting in and sometimes their family members can't interact with them. You're looking at somebody lying in a bed," says Deaconess ICU nurse manager Bailee Walters. "That's something I know the ICU team really struggles with, is that we don't want people to die alone. We want people to go surrounded by the people that they love, and not through a glass door and not on a screen."

Nurses who went into this field to heal people have seen so many patients die on a daily basis in recent weeks that they summarized the current mood in one word during their Friday morning meeting, Walters says: Hopeless.

"One of the things that we're seeing right now is that we are having more deaths than we are accustomed to and I think that really hurts people's souls because we're here to help people get better," Walters says. "This is the first time in my career I'm seeing ICU nurses break down and cry because they feel that the care they're providing is inadequate."

But the crush of patients has shown few signs of slowing down, and with schools recently starting up again and the colder weather moving more people moving indoors where transmission is easier, it's not clear if relief is in sight.

HITTING CRISIS LEVEL

There's an irony to the protests that have regularly happened outside Kootenai Health hospital's campus in Coeur d'Alene in recent months. As anti-mask and anti-vaccine protesters question whether hospitalizations are being exaggerated, and promote potentially dangerous "home remedies," their overall battle cry is that the pandemic can't possibly be this serious.But because the virus is so serious, visitors can't just walk through the ICU to "see for themselves" how bad things have gotten. That would put too many health care workers at risk of exposure at a time when they're needed to treat a record number of patients.

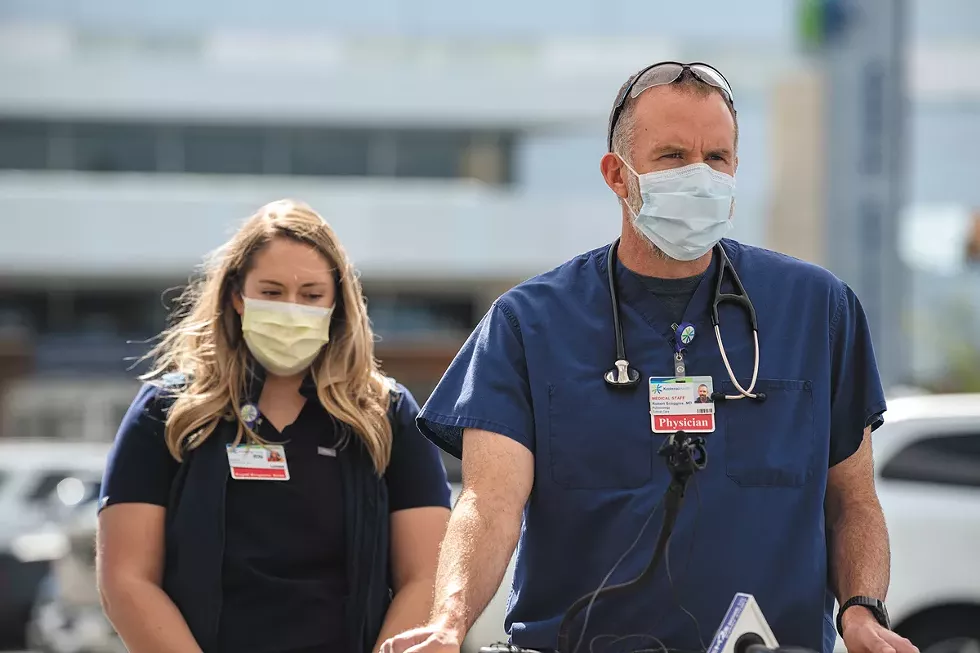

"I understand that it's very frustrating. A lot of people don't see what I see on a daily basis," says Dr. Robert Scoggins, medical director of Kootenai Health's ICU.

INLAND NORTHWEST COVID BY THE NUMBERS

Death reporting may be delayed, all numbers as of Monday, Sept. 20, 2021, unless otherwise noted.

SPOKANE COUNTY

814 deaths since the start of the pandemic, including 69 since Sept. 1

221 currently hospitalized

5,288 confirmed cases since Sept. 1

NORTH IDAHO (KOOTENAI, BONNER, BOUNDARY, BENEWAH AND SHOSHONE COUNTIES)

444 deaths (as of Sept. 16) since the start of the pandemic, including 47 since Sept. 1

125 currently hospitalized

2,989 confirmed cases since Sept. 1

PEND OREILLE, FERRY AND STEVENS COUNTIES

73 deaths since the start of the pandemic

63 hospitalizations since Sept. 1

783 confirmed cases in the two weeks up to Sept. 20

WHITMAN COUNTY

55 deaths since the start of the pandemic

19 hospitalizations since Sept. 1

415 confirmed cases since Sept. 1

It's true that most people who get COVID will in fact recover, he says, but for the 3 percent who end up in the ICU, it's a very dire situation with a low chance of walking out of the hospital again.

"I can tell you from taking care of these patients in the ICU that are very sick, they regret that they didn't take this very seriously. About 90 percent are unvaccinated," Scoggins says. "Watching somebody die from COVID is awful. I mean they struggle for breath and it's usually not fast. It's days and days of struggling. These are nice people, and as a staff we get to know some of them."

Overall, Kootenai Health has seen as many as 115 COVID patients at a time, with up to 40 or so in intensive care when the hospital typically only has 26 ICU beds for any illness. Even when the hospital might discharge a dozen patients in a day, they might have to admit another 15.

Not only has Kootenai had to add bed space for more patients in one of its teaching buildings, but it has had to get help from a military medical team sent by the U.S. Department of Defense, and another 100 or so nursing staff being provided by a federal contractor. The number of beds is less limiting a factor than the number of personnel needed to care for patients in those beds.

Yet protesters have gathered outside on Highway 95, where signs along the hospital's property say "We ♥ Our Health Care Workers," to loudly proclaim that the situation is being overblown.

"The main COVID unit is on the third floor that faces the highway, so the irony is that you are with your sick, intubated, proned, paralyzed patient, who you might have FaceTimed their family before you helped put their breathing tube in, and then you look out and you see [the protesters]," says Kootenai Health ICU nurse Emily Farness. "The patients, if they're not intubated, they hear it, too, and they look out their window and it's really demoralizing for everyone."

Some patients may have even been part of those protests at some point.

"I think a lot of them feel conflicted, because a lot of their friends and family might agree with the protestors outside, and they're now in a position where they're having to kind of reconcile those two realities," Farness says.

That includes the reality that those who get sick enough to end up in the ICU are likely to die or leave with permanent changes to their health.

"What's almost just as frustrating and heartbreaking as seeing people die is once people get that sick, they often never return to their prior quality of life," Farness says. "They might survive, but they're not returning to the jobs they had, they're not returning to their prior independence and abilities."

EMOTIONAL TOLL

Meanwhile, the patients who are dying are putting an extreme emotional toll on the health care workers who care for them.Whitney Warnock, an ICU nurse at Providence Holy Family hospital in north Spokane, says she might have seen one of her patients in the ICU die every six months before the pandemic. Now, as she works two or three 12- to 16-hour shifts per week, she's seeing someone die on every single shift.

"I was not used to this number of deaths. I've kind of put my heart and soul into my patient care and that's definitely taken a chunk out of me this go-around," Warnock says. "I think if there's one thing I wish everyone understood is, it's not your grandma and grandpa anymore. It's your mom and dad. It might be your sister and brother. We're seeing families getting taken out by it."

What's more, at Holy Family, relatives can only visit their sick loved one when it seems clear they're about to die, and there's a time limit on how long they can stay.

"I actually just had a patient who the family decided to go comfort care on and that was a very hard decision for them to make," Warnock says. "But you know, they're only allowed to be there for four hours, so they left and I had to hold his hand while he was dying, and that was really hard."

Ashley Blew worked in the Providence Sacred Heart ICU just after graduating from WSU nursing school in May 2020, and now works in an ICU in Boca Raton, Florida, which is also seeing a crush of patients. Blew says she's also had to be there with patients in their final moments. She can set up an iPad for families to video chat if it looks like their loved one might pass away, but some say no to that option.

"Some families opt to not, I guess, say goodbye, because they don't want to see their loved one in that state. They want to remember them as before," Blew says. "That's even harder on us because we're truly the only person there for that patient when they're decompensating or passing away. It's been pretty tough."

Arthurs, the Deaconess ICU medical director, says he's found himself going through more extreme emotions, at times having a short fuse as he talks to patient families who still question things like vaccine effectiveness.

"I've probably cried more this week at the end of long days than usual with so many deaths and so many really difficult conversations with family at the end of the day. It's hours on end," Arthurs says on Sept. 17. "The last two days I haven't gotten done with my work until the end of my day at 6 [pm] and then I've got two hours of conversations with families and then I try to go home and kiss my kids goodnight."

The sleep deprivation is setting in for many health care workers being asked to pull 16-hour shifts several times a week right now. And so is the frustration with how bad the situation has become.

"We really try to give everybody the same care, it doesn't matter your race or color or choice on vaccinations, you come in and we treat you with dignity as best we can," Arthurs says. "But there are days when you go through those emotions, frustration, sometimes anger, because you're dealing with all the stress of this."

The amount of attention COVID patients need once they end up in the ICU is very high, and nursing staff are so short right now in some hospitals that nurses are having to deal with quadruple their normal workload, Warnock says.

Jennifer Torres, another ICU nurse at Holy Family, says unlike before the pandemic, another thing on their pre-intubation checklist is finding a patient's cell phone before they're too far gone to unlock it for a call home. Sometimes patients are already so oxygen-deprived that their motor functions are impaired and they have to just tell the nurse their passcode, Torres says.

"We always try to look for a cell phone and get them to speak to their family for the last time, because it probably will be," she says.

Work has been such a struggle that Warnock says some of her co-workers have started group therapy with a co-worker's spouse who is offering pro bono services.

"I would really like to get out ... to all people in health care right now that have stayed, how valued they are, even if they don't feel like it," Warnock says. "In this group that I'm going to, we're all reporting incidents of insomnia, anxiety, irritability, feeling triggered when someone says, 'Have a good day at work.' That used to be such a great statement and now it's so triggering, because we don't have any good days."

Farness, the ICU nurse at Kootenai, says she and her co-workers similarly are leaning on each other for emotional support.

"My co-workers and I talk all the time about how we know we need to go to therapy, but we don't have the time or the energy to right now," Farness says. "With the onset of this delta wave, we recognize within ourselves these signs of PTSD. We've already been here before and the unknown that this is gonna keep on going, there's so much death and suffering that's uncalled for."

The surge is also reducing the ability for anyone with an emergency to get care.

PACKED EMERGENCY ROOMS, STRAINED RURAL CARE

One of the concerns many physicians have about the current surge is that patients who need to come get treatment for other urgent reasons will delay their visit.Patients are still encouraged to seek out care, but emergency room wait times may be significantly longer than usual. Some people are having to spend a day or more in the ER waiting for admission to a hospital, which means patients who are slightly less sick than they are also have to wait hours on end to get treated once that bed space frees up.

At smaller critical access hospitals that are licensed for up to 25 beds, sicker patients are being treated in-house because there's no space to transfer patients to larger hospitals.

Even as Bonner General Health hospital in Sandpoint and Gritman Medical Center in Moscow are both still offering the higher "contingency" standards of care despite the overall state declaration of crisis standards in Idaho, both have seen more patients being admitted.

"We're safe and open for folks to come in if they have an emergency or appointment," says Brad Gary, a spokesman for Gritman. "We have a dedicated COVID unit that has been at capacity on several occasions in the past couple of weeks, but we're still admitting COVID patients and patients for just about anything that needs to be treated."

As of Sept. 15, Gritman had seen 11 COVID admissions in the previous week.

When reached the week before, Erin Binnall, spokeswoman for Bonner General, noted that patients who typically would be transferred from the 25-bed facility (four of which are reserved for childbirth and family needs) are spending much longer at the Sandpoint facility.

At the time, nine COVID patients were admitted to the hospital, including four at ICU level who were either on ventilators or less invasive BiPAP breathing machines.

"The ability to transfer patients in need of specialty care is unlikely, there's no available beds," Binnall says. "Patients we typically transfer are being cared for here, increasing the burden on our staff, supplies and providers."

Likewise, Newport Hospital and Health Services in the neighboring northeast corner of Washington is struggling to transfer patients who need higher levels of care.

Typically, if someone needs ICU-level care, they'd be stabilized at Newport and then staff would find space for them at Providence or MultiCare facilities in Spokane, or maybe at Kootenai Health in Coeur d'Alene, says Dr. Geoff Jones, Newport's ER medical director.

But now, those places might have a waiting list of 10 or 15 people, which means calling Washington's wider health care network and sometimes even looking for hospital space in other states.

"I've done transfers to Missoula and both big hospitals in Boise," Jones says. "We've talked to hospitals in Utah, Salt Lake City, in Colorado. We've talked to folks in Oregon, Northern California."

When space is found, it creates a huge burden on emergency medical services, because these patients are so sick they need to be transferred by ambulance several hours away at times when helicopters aren't available, says Dr. Curtis Gill, who also works in Newport's ER.

Many COVID patients being transferred are on high-flow oxygen, which can be hard to ensure is available from a finite supply on a several-hour drive, Gill says.

Sometimes patients on less invasive BiPAP machines have to be put on ventilators to ensure they can remain stable for the ride, even though they wouldn't have been at that point yet if they could get into a closer hospital, he says. When they're transferred further away, it may also be harder for family to come visit or, should they recover, for them to get home.

"[This] is a low-income, underserved area. If I were to send a person to Seattle or Montana, trying to get home after that can be a major problem," Gill says. "[Family] can't ride along in the ambulance or go on the helicopter with them to these further away hospitals, so they have to find a car, find a friend, and ultimately if their loved one does well, they have to find the same resources again to pick them up and bring them home again."

Oxygen flow is also getting pushed to the limit within the smaller facilities, many of which have installed larger oxygen tanks to keep up with demand. Some patients are requiring 40 to 60 liters of oxygen flow per minute.

At that rate, pipes that weren't built with such a high demand in mind may freeze over as the liquid oxygen is vaporized into gas. A handful of times, Newport's system has been taken offline and patients had to be put on portable tanks until that could be fixed, Jones says.

It's just one reminder that COVID is unique in that it is hospitalizing such a large number of people with the same problems all at the same time.

"It seems like half the patients coming through the ER in recent weeks have been COVID positive and therefore have pretty severe disease," Gill says. "No other disease has had this many people in the hospital at the same time for the same reasons since I've been practicing medicine."

Other patients are struggling to get care because of it. Gill says he was shocked when he tried to transfer a heart attack patient to Spokane recently and couldn't. While Spokane's hospitals have to accept trauma patients, the heart attack didn't qualify.

"One of the most frustrating things for all of us is we've reached a point where we don't feel like we have to exist this way anymore. Last winter, before there was any vaccine for this, we went into work expecting to be overwhelmed with patients with no good options and nothing to do," Gill says. "And now things are different, we're still seeing this overwhelming thing, but the population we're taking care of is a very biased side of it."

Nearly all COVID hospitalizations are among the unvaccinated, which reinforces that vaccination is one of the most effective tools in preventing severe infections.

HOW TO REACH THE SKEPTICAL

ICU nurses and doctors say that some of the patients who are extremely ill by the time they reach their care have asked when they could get vaccinated. Those who recover could ultimately get the vaccine to help boost their immunity later on, but vaccines don't treat the infection once it has set in like that, when outcomes are unlikely to be good.Holy Family ICU nurse Warnock says she's had people tell her various reasons they didn't get a vaccine.

"By the time we see them it's too late, so that's very heartbreaking," Warnock says. "I asked one patient why she didn't get the vaccine, because I am curious [about] people's reasoning. I don't judge them, I just want to know. She said that her friends told her to wait. She's no longer with us."

Newport ER director Jones says in his work as a family physician within the health system, he's asking every patient about this topic and trying to answer as many questions as he can to encourage people to get vaccinated.

"Our community here is extremely supportive. You know, people are very kind, people at the coffee stand, patients that you talk to. ... And yet, we have a really low vaccination rate," Jones says. "I'd say the best thing you can do to support us is to get vaccinated."

He's actually been surprised at how receptive most of his family medicine patients are when he has that conversation with them.

"What really wears me out is when our hospital staff is also adamantly opposed to vaccination," Jones says. "You almost feel like you're fighting it in the community, you're fighting it at work, and you just never catch a break."

Similar to other hospitals around Washington, some nursing staff at Newport have said they will refuse to get vaccinated despite Gov. Jay Inslee's mandate that healthcare workers receive the vaccine. Some may lose their jobs or quit.

"You almost feel like you're fighting it in the community, you're fighting it at work, and you just never catch a break."

"These are really good people that I think are making choices that put them and all the rest of us at risk," Jones says.

Nurses Warnock and Torres say they're both vaccinated, but they disagree with the mandate.

"I think whatever their reasons are are personal, and I don't judge anyone for that," Torres says. "I don't think anybody, especially in what we do, I don't think anyone is taking that decision lightly."

Both nurses worry it'll make short-staffed hospitals even more strained.

"We're already really struggling for help and it's getting rid of a lot of help and a lot of valued team members," Warnock says. "But I'm also very pro-vaccine and I sleep a lot better at night knowing that everyone I love and hold dear to my heart decided to take that step for themselves." ♦