Friday, June 30, 2017

Nearly 50 dangerously adorable marmot pictures; seek them out on your own!

This week, our Outdoors Issue tackles the marvelous spectacle of urban wildlife. Naturally, that includes God's most majestic creature, the yellow-bellied marmot. Marmots that live in urban environments are unheard of in most cities across the United States, but in Spokane, the creatures have presumably been attracted enough by our low cost of living and thriving downtown to move to the city.

As a general rule, the best places to look for marmots are near rivers, by big piles of rocks. But if you want a few specific places to look for marmots, we're here to help. Here are a few of my favorite marmot-spotting spots near downtown Spokane:

Sometimes these marmots pop out of the big boulders like a game of Whack-A-Mole. Other times they stand still against the skyline, like silent protectors. If you're lucky, you can spot three or more lounging on a single group of rocks, or streaking across the dirt field to duck under the big shipping containers.

Notice how some of these marmots have luscious coats worthy of Cruella de Vil's Marmot signature collection, while others look like scraggly river rats?

Elizabeth Addis, assistant professor of biology at Gonzaga University, has studied urban marmots and offers an explanation for the variance.

"The ones that didn’t have any fur were parasitized by skin mites," Addis says "They also had lower levels of triglycerides."

Triglycerides are found in fat, meaning the marmots with the gorgeous coats generally have better diets.

Tags: Wildlife , outdoors , marmots , downtown Spokane , Kendall Yards , Glover Field , Centennial Trail , News , For Fun! , Image

ON INLANDER.COM

Address unknown

What happens when Spokane County Sheriff's deputies can't find the house where a burglary was reported? They go to a different house, knock on the door, confront a 22-year-old watching Netflix, point a gun at him, then tell him "You're lucky I didn't f—-in' shoot you."

Min at work

We dive into the strengths and weaknesses of the controversial UW minimum wage study.

Remaking the grade

Like middle school, kids? Well, how would you like three years of middle school?

Got mother's milk?

There are this weird compounds called "oligosaccharides" in mother's milk that babies can't even digest? So what's their deal?

Fish and sticks on osprey-per-view

Some of the sweetest osprey pics of the summer, as he goes hunting for a fish and, uh, a cool stick.

IN OTHER NEWS

The art of compromise

With less than 24 hours left on the clock before a state government shutdown, House Democrats are getting the revenue they want for education, but they're paying for it largely with the method — property taxes — put forward by Senate Republicans. (The News Tribune)

Say it ain't so, Joe

After President Trump launches into a sexist Twitter rant suggesting, among other things, that Morning Joe's Mika Brzezinski was bleeding as a result of plastic surgery, she and co-host Joe Scarborough respond, suggesting that the National Enquirer was going to publish a negative article about them unless they begged Trump to stop it. (Washington Post)

The big drop

The amount of funding that had been scheduled to be spent on Medicaid would plummet by 35 percent under the Republican Senate's health care plan. Does that count as a cut or just a slower growth of spending? (New York Times)

Tags: Morning briefing , News , minimum wage , middle school , osprey , budget , Olympia , Trump , Morning Joe , health care , Image

Thursday, June 29, 2017

Swim safely this summer!

Sunny skies, perfect temperatures, and the weekend is in sight. Nothing sounds better than a day of boating, floating or swimming under cloudless skies. But for all the thousands of Pinterest-worthy summer outings, there are inevitably a few stories — and even one is too many — of summer fun gone desperately wrong. Drowning is the most common cause of death among 1-to-5-year-olds, writes Dr. Matt Thompson in a recent issue of InHealth. "What does that mean for parents? Be paranoid when it comes to bathtubs, kiddie pools, big pools and lakes. Use life jackets liberally and make sure they keep your kid afloat, should he or she lose consciousness."

The Spokane Regional Health district offers a coupon for a 25 percent discount on life jackets at area Big 5 sporting goods stores, as well as all kinds of tips on swimming safety. Remember: Drowning can be silent and swift, occurring in as little as 30 seconds.

New docs on call

The big day is almost here. On July 1, new interns will take to the halls of hospitals across America. These newly minted doctors will face many challenges — from breaking bad news to patients to battling insurance companies. And often, they'll be doing it all on very little sleep. New guidelines allow interns to work up to 28 hours in a row. Read about the wisdom behind the system in InHealth.

Magical mystery milk

Why in the world would human mother's milk contain multiple, highly specific, energy-filled compounds, called human milk oligosaccharides, that babies aren't even able to digest? Scientists puzzling over this mystery have reached a surprising answer, says the New Yorker. The compounds — which are the third-most abundant ingredient in breast milk, after lactose and fats — aren't there to directly nourish the baby at all; they're there to nourish one particular gut microbe called B. infantis. It's an interaction that may have long-term impacts on the baby's immune system and brain development.

Read more in the latest issue of InHealth.

Tags: InHealth , summer , water safety , life jackets , interns , new doctors , mother's milk , Image

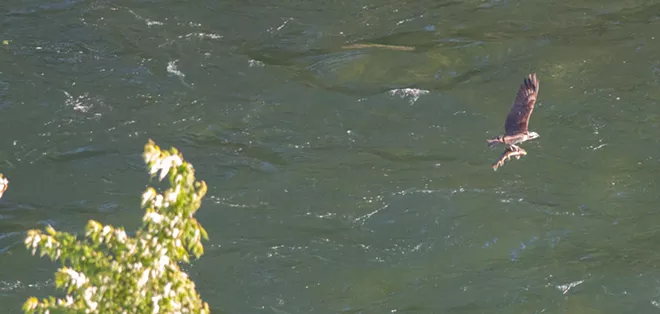

Sucker fish, beware; you are being hunted

This week's Outdoors issue of the Inlander celebrates the adorable and awe-inspiring presence of wildlife near Spokane's urban core.

This year, I had but one bullet point on my summer bucket list:

• Get a sweet picture of an osprey carrying a fish.

The evening before my story on urban wildlife in Spokane was due, I finally got lucky. Pausing on the Centennial Trail near the Night Market in Kendall Yards, I spotted an osprey searching for food.

After diving down to the Spokane River to snatch a sucker fish, the osprey skims over the Spokane River, then glides above the Peaceful Valley neighborhood.

Then he heads for the Maple Street Bridge, shooting upward over the evening's traffic.

Then, he's flying west over Riverside Avenue...

... swinging by

...soaring over the towers of the Steam Plant and the Cathedral of our Lady of Lourdes...

... and making a cameo

Finally, he flies back across the river, directly over my head, delivering that photograph I've been seeking for two straight summers:

Earlier this year, I also managed to take a few shots of an osprey — maybe the same osprey — gliding down into the gorge, ripping a big stick off a tree, and taking it back to its nest. (The stick really ties the room together.)

On top of that, I managed to snap a few pics of the

That's Spokane for you.

Tags: Osprey , Wildlife , Outdoors issue , For Fun! , Image

Unanimous decision will help district meet growing student enrollment numbers

Spokane Public Schools will now start planning to move 6th grade from elementary school into middle school, a decision that will help the district meet growing student enrollment.

The school board voted 4-0 in favor of the idea Wednesday night, after a year-long study by a Spokane Public Schools grade configuration committee concluded that it was the best way to solve overcrowding in elementary schools. Board member Paul Schneider was absent.

"I feel confident that because there was so much community input, that the outcome was also good," said Sue Chapin, school board vice president, during the meeting.

Currently, elementary schools in Spokane Public Schools are kindergarten through sixth grade, middle schools are seventh and eighth grade, and high schools are ninth through 12th grade. The grade configuration committee, with the help of public input, examined multiple ways to reconfigure the grades so that the district wouldn't have to build five or more elementary schools to alleviate overcrowding in the next bond. The district considered keeping the current configuration, or switching to a K-8, 9-12 model.

Few people supported a K-8, 9-12 configuration, according to a survey conducted by the district through Thoughtexchange. More than 95 percent of participants had negative thoughts about a K-8, 9-12 grade configuration, and only 1 percent had positive thoughts about it. Similarly, 91 percent of people negatively viewed the current grade configuration. But the K-5, 6-8, 9-12 configuration chosen by the board last night enjoyed overwhelming support at 91 percent. More than 3,720 people participated in the survey.

Most districts in Washington already place sixth graders in middle school instead of elementary school. Mark Anderson, SPS associate superintendent, has said there is little research showing that one model produces better outcomes for students than another. The benefits of moving sixth grade to middle school, according to the district, is that middle schools can offer sixth graders more academic opportunities, it better aligns with learning standards, and it extends the time between transitions for students — though the K-8 model would have eliminated an extra transition entirely.

This decision will also mean that the district will have to build fewer new facilities with its next bond in 2021, compared to other configuration options.

Tags: Spokane Public Schools , grade configuration , sixth grade , middle school , elementary school , class size , News , Image

Findings contradict UC Berkeley study on Seattle's minimum wage, trigger 'wonk war'

Choose your own Seattle minimum-wage study adventure!

Do you love the minimum-wage hike? Then you'll love the study from UC Berkeley's Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics that says Seattle's minimum wage hike from $11 to $13 an hour helped food-service workers make more money, without harming hours or employment.

On the other hand, do you hate the minimum-wage hike? Then you'll love the study from the University of Washington that uses government payroll data to find that because of a reduction of hours, the implementation of the minimum wage actually reduced wages for workers making $19 an hour or less by an average of $125 per month. The hours they lost erased the gains they made with pay increases.

The resulting disparity in conclusions has catalyzed a wonk war, with those on the right and the left eager to undercut the conclusions of one study or the other.

The UW study made headlines precisely because it seemed to contradict the vast body of research showing little to no effect from prior wage hikes. On the other hand, most of those studies were looking at hikes much less dramatic than Seattle's.

So yesterday, the Inlander spoke with Jacob Vigdor, the UW study's director, about the strengths and the weaknesses of the UW study, and what it told us about Seattle's divergent restaurant scene.

The big takeaway: The UW study produced different results because it's providing different answers to a different set of questions with different sets of data.

"The issue that a lot of previous studies have faced is you don’t actually get to see what people’s wage rates are," says Vigdor, a professor at the UW's Evans School of Public Policy & Governance and former faculty member at Duke University's Sanford School of Public Policy.

"You have to pick something else … You pick a sector of the workforce that you think the work being done is low-wage work."

"The issue that a lot of previous studies have faced is you don’t actually get to see what people’s wage rates are," Vigdor says.

As a result, many previous studies look at just teenagers, or just the restaurant industry.

That's what the Berkeley study, released last week, did. It found that pay for food-service workers increased increased by about 1 percent in the food service industry, and 2.3 percent in limited-service restaurants (think fast-food joints).

But this approach has two weaknesses: First, only about 30 percent of the low-wage work in Seattle is in the restaurant industry, Vigdor says, while the rest is in other areas. Think department stores, movie theaters, bowling alleys, child care. Focusing just on the restaurants misses all these other types of low-wage workers in industries facing different economic winds.

Second, you end up inadvertently including workers who aren't low-wage workers — who are actually getting paid much better salaries — and lumping them in with minimum-wage employees.

Tags: minimum wage , Seattle , study , University of Washington , Berkeley , News , Image

It's dark — after 8:30 pm in December — and two Spokane County Sheriff's deputies surround a house on North Five Mile Road, guns

The only problem is, they're snooping around the wrong house. They had been given the correct address, but they couldn't find the house and assumed the caller was mistaken.

Deputy Evan Logan walks around back and shines his lig

Deputy Robert Brooke walks to the front of the house and shines his flashlight

Meanwhile, Connor Griffith-Guerrero, the 22-year-old who lives in the house, is watching a movie on Netflix in the basement. He sees the deputies' flashlights and walks to the main floor to investigate. Griffith-Guerrero cracks open the front door, sees the deputy's gun and screams as he

"Open the door!" Brooke says. "Sheriff's Department!"

On hearing that the flashlights and guns are being held by police, Griffith-Guerrero opens the door. He's ordered out of his house and onto his knees. The deputies put him in handcuffs at gunpoint, according to court documents.

"You're lucky I didn't f—-in' shoot you," Brooke says to Griffith-Guerrero, according to court documents.

Tags: Spokane County Sheriff's Office , police , search and seizure , Fourth Amendment , lawsuit , Logan Evans , Robert Brooke , U.S. District Court , News , Image

ON INLANDER.COM

SMALL TOWNS: The tiny town of Latah — population 195 — is struggling to survive. At least one town councilmember isn't convinced that it should.

IMMIGRATION: The U.S. State Department released guidelines for President Trump's travel ban that goes into effect today after the Supreme Court reversed lower courts' decisions to halt the controversial policy. The seemingly arbitrary guidelines allow stepsiblings and half-siblings, but not nieces or nephews; parents, but not grandparents. (via New York Times)

GO, FISH! OTTO the Spokanasaurus, the longtime Spokane Indians mascot, has a new buddy. A partnership between the minor league baseball team and the city of Spokane aims to raise awareness about improving the health of the Spokane River. The new mascot and uniform are inspired by the redband trout, native to the Inland Northwest.

IN OTHER NEWS

State budget deal done; details to come

Washington state lawmakers have reached a "tentative" deal to fund the government through 2019, but they're closely guarding specific details. One major question: Whether the budget will comply with the state Supreme Court's order in the McCleary decision to properly fund public education. (Seattle Times)

Excessive force OK, but Spokane silenced

A Spokane jury was not allowed to comment on the record beyond its decision to absolve two Spokane County deputies of excessive force that took a man's life in 2013. Jurors sent this statement to the judge, but weren't allowed to elaborate in court: "While the jury exonerate Deputy Audie and Deputy Paynter from the charge of using excessive force during William Berger's arrest, we have reservations regarding the actions of Deputy Audie on June 6, 2013."

Berger died of oxygen deprivation after one deputy used a controversial neck restraint, similar to the move that killed Eric Garner in New York in 2014. (Spokesman-Review)

High-ranking Vatican official accused of sexual assault

Cardinal George Pell, a top advisor to Pope Francis, has been charged with sexual assault in Australia. Pell is the highest ranking Vatican official charged with criminal sexual abuse. Pell denies the accusations, some of which involve minors. (New York Times)

Wednesday, June 28, 2017

A first-of-its-kind study by University of Washington Medicine researchers has identified the type of fireworks that cause the most severe injuries — shell-and-mortar fireworks.

The study shows that regular off-the-shelf, legal shell-and-mortar fireworks account for nearly 40 percent of fireworks-related injuries resulting in hospitalization, and 86 percent of overall fireworks injuries among adults.

Since 1999, about 10,500 people have been treated for fireworks-related injuries every year in the U.S., according to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. However, there hasn’t been a lot of data collected on what types of fireworks cause the most severe injuries, says Dr. Monica Vavilala, director of the Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center, in a statement.

These style of fireworks typically instruct users to put the barrel-like mortar on the ground, drop in the shell, light the fuse and run. However — even when done correctly — accidents can still occur, with severe consequences.

The study reviewed the cases of 294 people admitted to Harborview Medical Center for severe fireworks injuries from 2005 to 2015 to determine which types of fireworks cause the most injuries, as well as identifying injury patterns and severity.

“We treated about 30 patients for hand injuries requiring surgery during the July 4th weekend last year,” says Vavilala.

Ninety percent of the patients in the study were male, and the mean age was 24. Sixty-one percent of patients suffered hand injuries, with 37 percent requiring at least one partial or whole finger/hand amputation. Twenty-one of the patients suffered eye injuries, with two-thirds of those suffering permanent vision loss. Of the 294 patients, 11 had to have an eye removed.

Tags: fireworks , UW , University of Washington , News , Image

The teams partners with the city for a river health and awareness campaign

A native trout has inspired a new uniform design for the Spokane Indians baseball team.

The Indians announced the design on Wednesday, as well as a new partnership with the city of Spokane, aiming to raise awareness of and encourage citizens to participate in maintaining and improving the health of the Spokane River.

The promotion, called the Redband Rally Campaign, got its name from the redband trout, a distinctive fish only found in the Inland Northwest. Otto Klein, the Indians' senior vice president, says that current trout numbers are down compared to historical counts.

“We can get those numbers back up,” Klein says. “It all starts with a clean river.”

The campaign will be collecting donations — including by text — at games to give to local river cleanup organizations. Five dollars from each purchase of merchandise featuring the Redband logo will also be donated.

Indians players will don the new uniforms five times this season, beginning with the July 8 game against the Hillsboro Hops.

A Redband Trout mascot for the campaign will also make its fir

Klein is particularly excited about the new Redband Headbands. To be passed out for free during the middle of the sixth inning on July 8, these headbands feature the same red and blue spots and stripes as the new uniforms, but also include information on the Redband Rally Campaign on the inside of the headband.

The city of Spokane is supporting the Redband Rally Campaign with an initial $25,000 contribution.

In a press release, Mayor David Condon says he hopes the campaign can encourage participation in river cleanup, and draw support for a $340 million investment in water quality improvement projects.

Tags: Spokane Indians , redband trout , Redband Headbands , Redband Rally Campaign , uniforms , mascot , News , Image